Comet tail sign

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

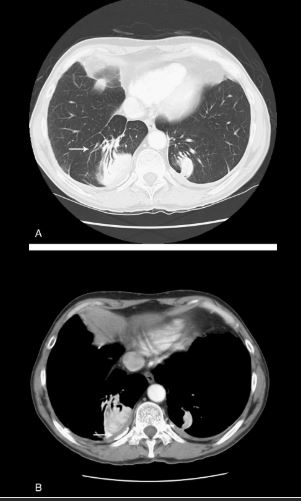

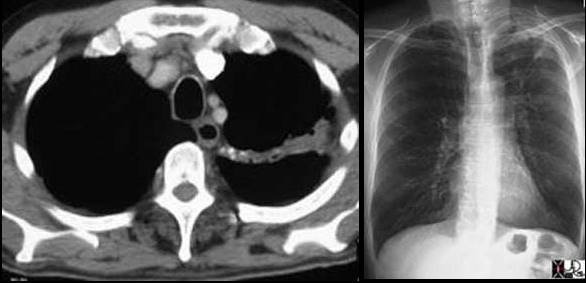

Identified as a curvilinear opacity arising from a rounded, subpleural opacity on CT (Fig. 4A, arrow), the “comet tail” denotes the distorted curving of pulmonary vessels and bronchi toward a region of round atelectasis.14–17 The atelectatic lung typically abuts an area of pleural effusion or thickening, and there are associated signs of volume loss. Round atelectasis is an unusual form of atelectasis most commonly associated with asbestos-related pleural disease (Fig. 4B, arrow), but also seen with other chronic forms of pleural disease, such as tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, pulmonary infarcts, or congestive heart failure.14–17 It is also known as atelectatic pseudotumor, folded lung, or Blesovsky syndrome, after the physician who initially postulated an association with asbestos exposure.18 Most often found in the posterior aspect of the lower lobes, it may demonstrate significant contrast enhancement and contain air bronchograms.14–17 Histopathology demonstrates fibrous thickening of the visceral pleura with extensive pleural folding and invagination.19 The exact cause is still debated. One theory suggests that a pleural effusion is the inciting event causing passive atelectasis and pleural invagination.20 Fibrous adhesions will eventually develop between the visceral and parietal pleural surfaces, so that when the effusion clears, the entrapped lung folds in on itself. An alternate theory suggests that a focal inflammatory pleural fibrotic response secondary to irritants such as asbestos, is solely responsible for causing invagination of the pleura and regional atelectasis of the subjacent lung.14,19,21

Juxtaphrenic peak sign

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

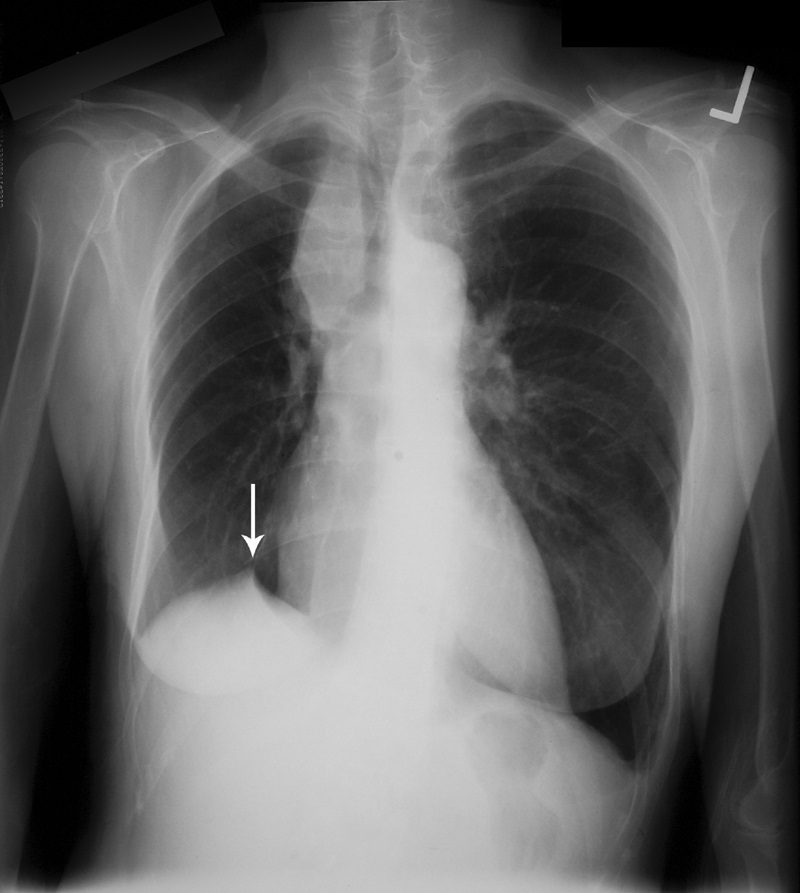

This sign, first documented by Kattan et al in 1980,49 is an ancillary sign of upper lobe collapse, depicted as a triangular opacity projecting superiorly over the medial half of the diaphragm, at or near its highest point (Fig. 16). It is most commonly related to the presence of an inferior accessory fissure.49,50 Although the mechanism is not certain, one theory suggests it is due to the negative pressure of upper lobe atelectasis causing upward retraction of the visceral pleura and extrapleural fat protruding into the recess of the fissure.49 A recent retrospective analysis of patients who have undergone upper lobectomies suggests that the prevalence of the sign increases in the ensuing weeks after intervention and documents its utility in specifically recognizing the type of surgery.51

Luftsichel sign

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

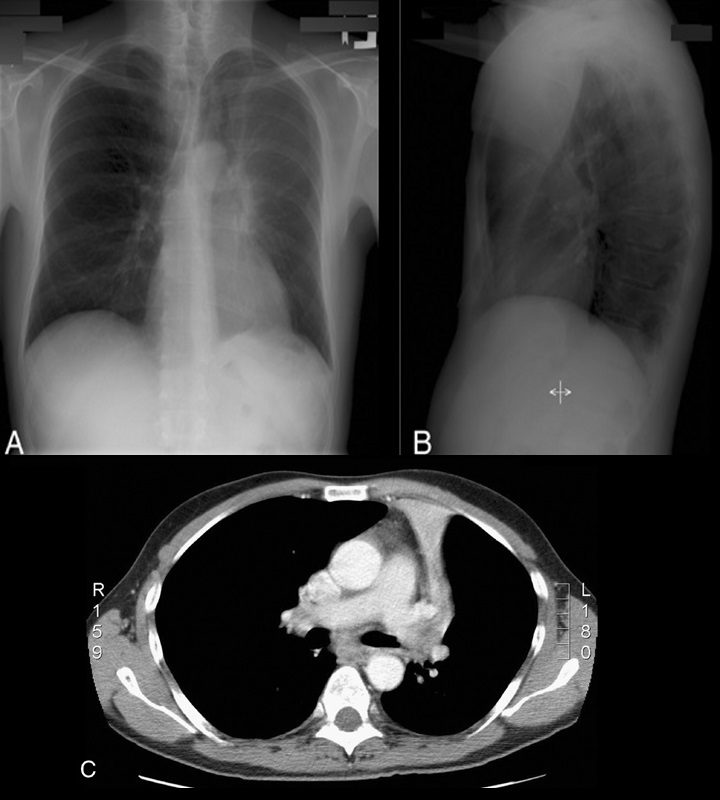

The word Luftsichel is German for “air crescent.” The finding is seen in the setting of left upper lobe collapse. Due to the absence of a minor fissure on the left, as the left upper lobe collapses, the major fissure assumes a vertical position roughly parallel to the anterior chest wall.4 As volume loss progresses, the fissure continues to migrate more anteriorly and medially until the atelectatic lobe is contiguous with the left heart border, effectively obliterating its contour on the frontal radiograph (Figs. 17A–C). With movement of the apical upper lobe segment anteromedially, the superior segment of the left lower lobe hyperinflates and fills the vacated apical space.4,52 Occasionally this segment will insinuate itself between the aortic arch and the collapsed left upper lobe creating a sharp outline, or periaortic lucency, described as the Luftsichel.3,4,52

Silhouette sign

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

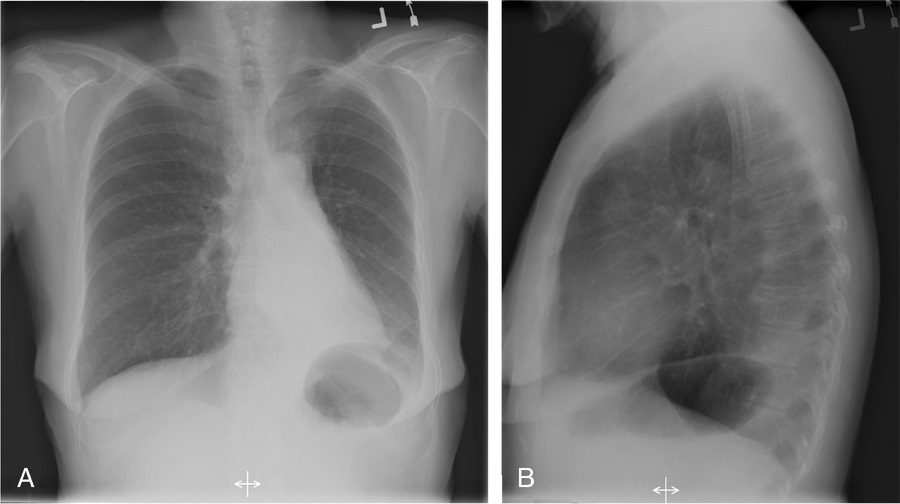

If the left heart border is partially or completely obliterated, the lingula is the region of involvement. Conversely, the absence of the silhouette sign can help in further localizing a lesion. With lower lobe disease, the right or left heart border on the side of involvement is preserved, whereas the silhouette of the hemidiaphragm is obliterated in cases of lower lobe collapse or consolidation (Fig. 21). The basic tenets of the silhouette sign are used to explain various other signs discussed previously, such as the cervicothoracic and hilum overlay sign.

Left image: In this patient with TB there is a linear band like density with calcifications in the LUL characteristic of atelectatic change in the LUL. This loss of volume is associated with fibrosis and retraction seen on the CXR in the following image. Courtesy of: Ashley Davidoff, M.D.

Left image: In this patient with TB there is a linear band like density with calcifications in the LUL characteristic of atelectatic change in the LUL. This loss of volume is associated with fibrosis and retraction seen on the CXR in the following image. Courtesy of: Ashley Davidoff, M.D.

Signs and Findings in Chest Radiology TCV link