Asbestosis refers to chronic, diffuse interstitial fibrosis of the lungs caused by prolonged inhalation of asbestos fibers. It is a form of pneumoconiosis, characterized by scarring of the lung parenchyma, primarily involving the lower zones, and is typically associated with long-term occupational exposure to asbestos. Radiological imaging plays a key role in diagnosing and monitoring this condition.

Radiological Features

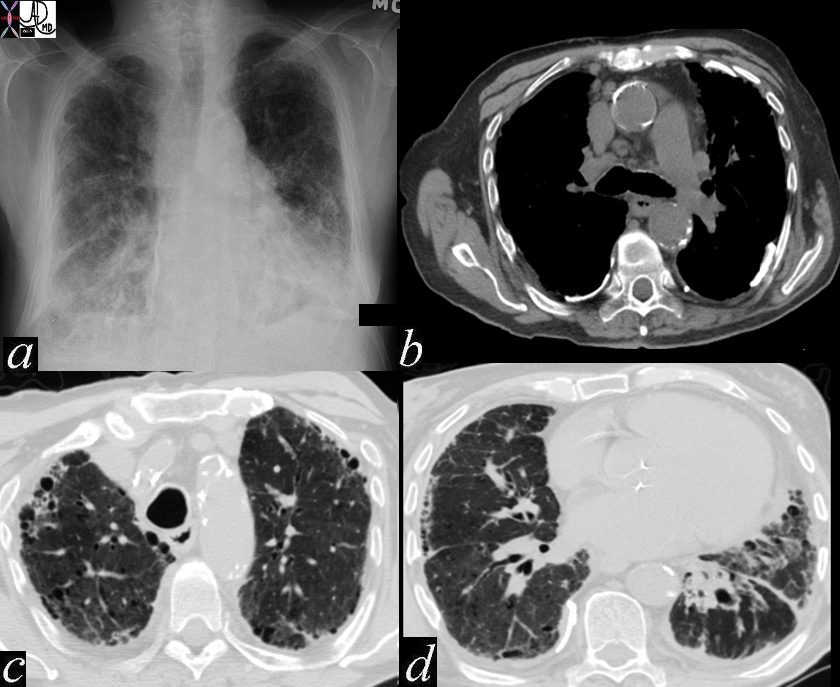

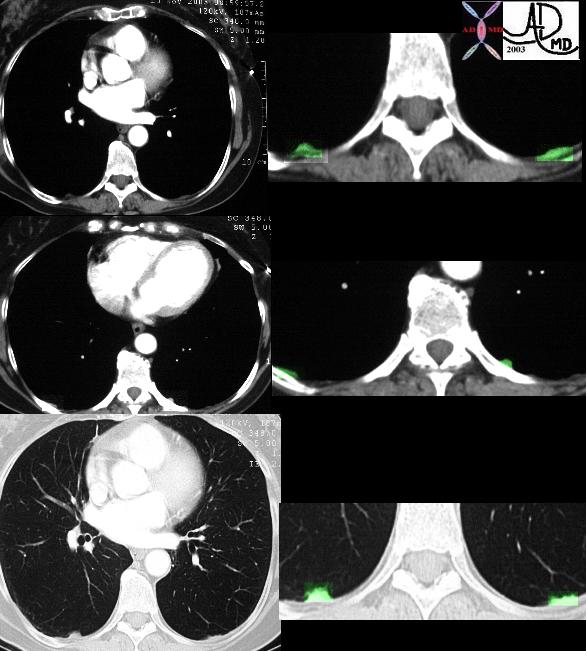

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonvein.net lungs-0771

Ashley Davidoff MD

TheCommonVein.net.

32697

Chest X-Ray (CXR):

Ashley Davidoff MD thecommonvein.net 47060c01

-

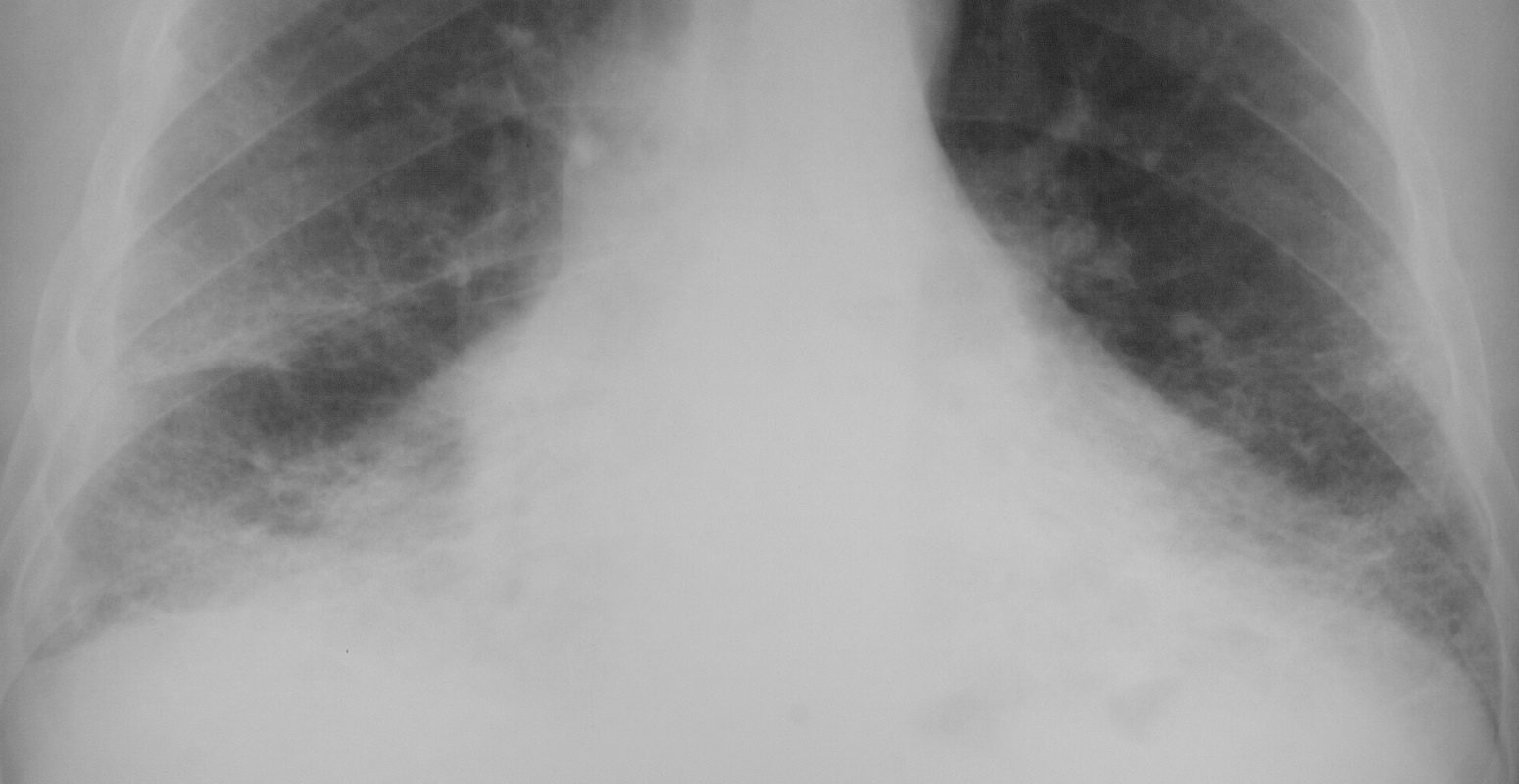

- Reticular Opacities:

- Fine, irregular linear opacities predominantly in the lower lung zones.

- Honeycombing:

- Seen in advanced cases, indicating end-stage fibrosis.

- Pleural Changes:

- Pleural Plaques: Localized, calcified or non-calcified areas of pleural thickening, often on the parietal pleura and diaphragmatic surfaces.

- Diffuse Pleural Thickening.

- Volume Loss:

- Lower lobes may show reduced volume due to fibrosis.

- No Nodules:

- Unlike some other pneumoconioses, asbestosis does not typically present with discrete nodules.

- Reticular Opacities:

- High-Resolution CT (HRCT):

- Early Findings:

- Ground-Glass Opacities: Hazy areas indicating early fibrosis.

- Subpleural lines: Thin, linear densities parallel to the pleural surface.

- Interstitial Fibrosis:

- Reticulations: Thickened interlobular septa, predominantly in the subpleural and basal regions.

- Honeycombing: Clusters of cystic airspaces in the peripheral and basal lung regions in advanced cases.

- Pleural Findings:

- Pleural Plaques: Hyperdense areas of pleural thickening, often calcified.

- Rounded Atelectasis: Focal lung collapse associated with pleural thickening, forming a “comet-tail” appearance.

- Traction Bronchiectasis:

- Airway dilation due to surrounding fibrotic retraction.

- No Significant Nodularity:

- Helps differentiate asbestosis from silicosis or coal worker’s pneumoconiosis.

- Early Findings:

Associated Features

- Pleural Plaques:

- Hallmark of asbestos exposure but not diagnostic of asbestosis.

- Calcified or non-calcified, predominantly involving the lower thoracic cage and diaphragm.

- Asbestos-Related Lung Cancer:

- Increased risk, often seen as a mass lesion on imaging.

- Mesothelioma:

- Presents as diffuse pleural thickening or pleural masses.

Differential Diagnosis

When evaluating radiological findings, it is important to differentiate asbestosis from other interstitial lung diseases:

- Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF):

- Similar basal and subpleural fibrosis, but lacks pleural plaques or history of asbestos exposure.

- Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis:

- Centrilobular nodules and ground-glass opacities predominate.

- Sarcoidosis:

- Upper lobe predominant with perilymphatic nodules.

Radiological Stages

- Early-Stage:

- Ground-glass opacities and subpleural lines.

- Intermediate-Stage:

- Reticular opacities and traction bronchiectasis.

- Advanced-Stage:

- Honeycombing, extensive fibrosis, and architectural distortion.

Role of Imaging in Diagnosis

- Diagnosis:

- Requires integration of radiological findings with clinical history and evidence of asbestos exposure.

- Disease Monitoring:

- CT is preferred for early detection and follow-up of fibrosis progression.

- Screening for Complications:

- HRCT helps identify pleural mesothelioma or asbestos-related lung cancer.

Key Radiological Clues for Asbestosis:

- Basal-predominant reticular opacities and honeycombing.

- Pleural plaques with or without calcifications.

- No significant nodularity, distinguishing it from silicosis or coal workers’ pneumoconiosis.

Nutshell Buzz

UIP with pleural disease

basilar

subpleural

honeycomb

reticulations

bronchiectasis bronchiolectasis

Asbestosis refers to chronic, diffuse interstitial fibrosis of the lungs caused by prolonged inhalation of asbestos fibers. It is a form of pneumoconiosis, characterized by scarring of the lung parenchyma, primarily involving the lower zones, and is typically associated with long-term occupational exposure to asbestos. Radiological imaging plays a key role in diagnosing and monitoring this condition.

Radiological Features

- Chest X-Ray (CXR):

- Reticular Opacities:

- Fine, irregular linear opacities predominantly in the lower lung zones.

- Honeycombing:

- Seen in advanced cases, indicating end-stage fibrosis.

- Pleural Changes:

- Pleural Plaques: Localized, calcified or non-calcified areas of pleural thickening, often on the parietal pleura and diaphragmatic surfaces.

- Diffuse Pleural Thickening.

- Volume Loss:

- Lower lobes may show reduced volume due to fibrosis.

- No Nodules:

- Unlike some other pneumoconioses, asbestosis does not typically present with discrete nodules.

- Reticular Opacities:

- High-Resolution CT (HRCT):

- Early Findings:

- Ground-Glass Opacities: Hazy areas indicating early fibrosis.

- Subpleural lines: Thin, linear densities parallel to the pleural surface.

- Interstitial Fibrosis:

- Reticulations: Thickened interlobular septa, predominantly in the subpleural and basal regions.

- Honeycombing: Clusters of cystic airspaces in the peripheral and basal lung regions in advanced cases.

- Pleural Findings:

- Pleural Plaques: Hyperdense areas of pleural thickening, often calcified.

- Rounded Atelectasis: Focal lung collapse associated with pleural thickening, forming a “comet-tail” appearance.

- Traction Bronchiectasis:

- Airway dilation due to surrounding fibrotic retraction.

- No Significant Nodularity:

- Helps differentiate asbestosis from silicosis or coal worker’s pneumoconiosis.

- Early Findings:

Associated Features

- Pleural Plaques:

- Hallmark of asbestos exposure but not diagnostic of asbestosis.

- Calcified or non-calcified, predominantly involving the lower thoracic cage and diaphragm.

- Asbestos-Related Lung Cancer:

- Increased risk, often seen as a mass lesion on imaging.

- Mesothelioma:

- Presents as diffuse pleural thickening or pleural masses.

Differential Diagnosis

When evaluating radiological findings, it is important to differentiate asbestosis from other interstitial lung diseases:

- Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF):

- Similar basal and subpleural fibrosis, but lacks pleural plaques or history of asbestos exposure.

- Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis:

- Centrilobular nodules and ground-glass opacities predominate.

- Sarcoidosis:

- Upper lobe predominant with perilymphatic nodules.

Radiological Stages

- Early-Stage:

- Ground-glass opacities and subpleural lines.

- Intermediate-Stage:

- Reticular opacities and traction bronchiectasis.

- Advanced-Stage:

- Honeycombing, extensive fibrosis, and architectural distortion.

Role of Imaging in Diagnosis

- Diagnosis:

- Requires integration of radiological findings with clinical history and evidence of asbestos exposure.

- Disease Monitoring:

- CT is preferred for early detection and follow-up of fibrosis progression.

- Screening for Complications:

- HRCT helps identify pleural mesothelioma or asbestos-related lung cancer.

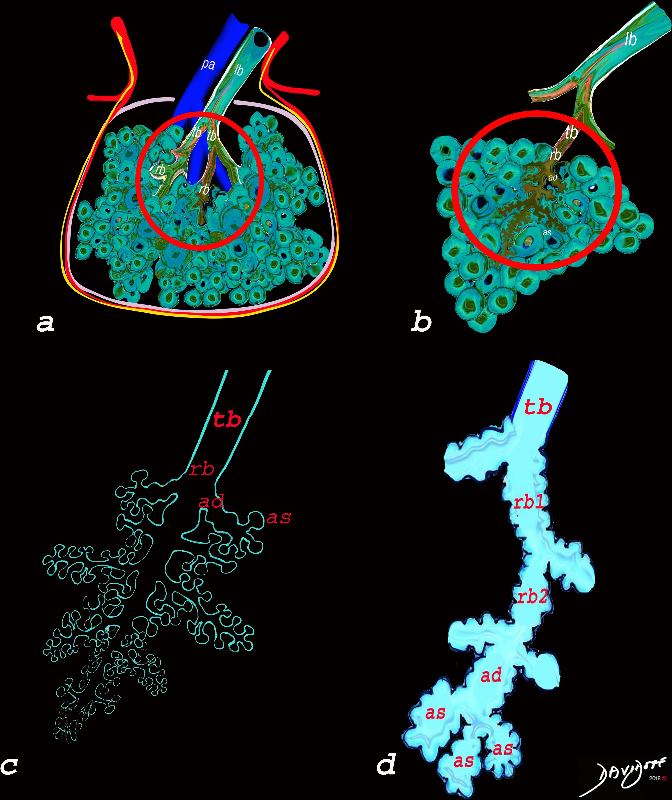

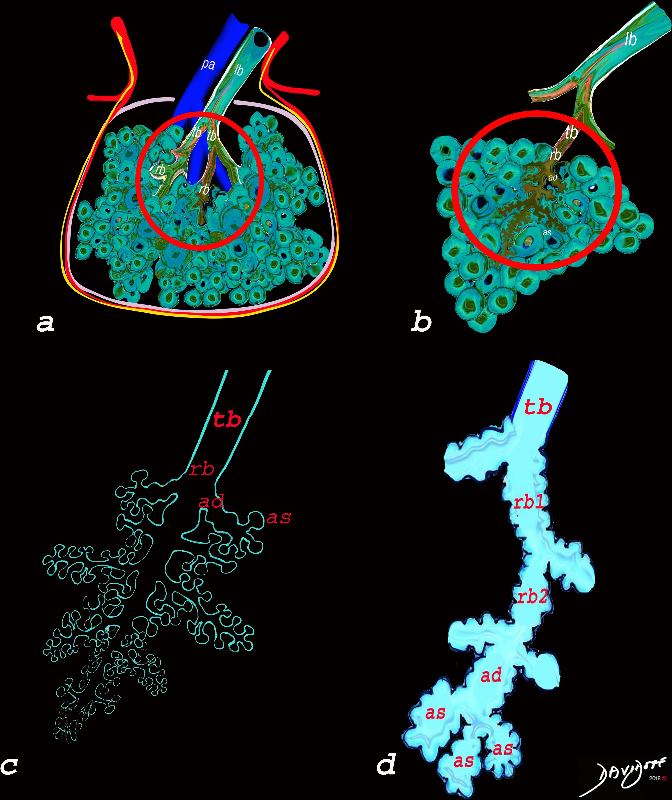

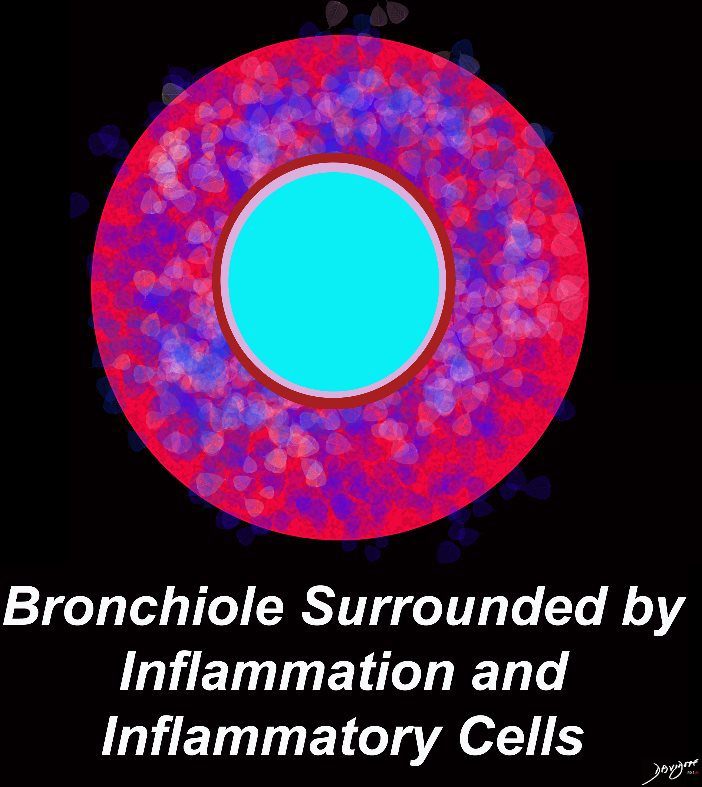

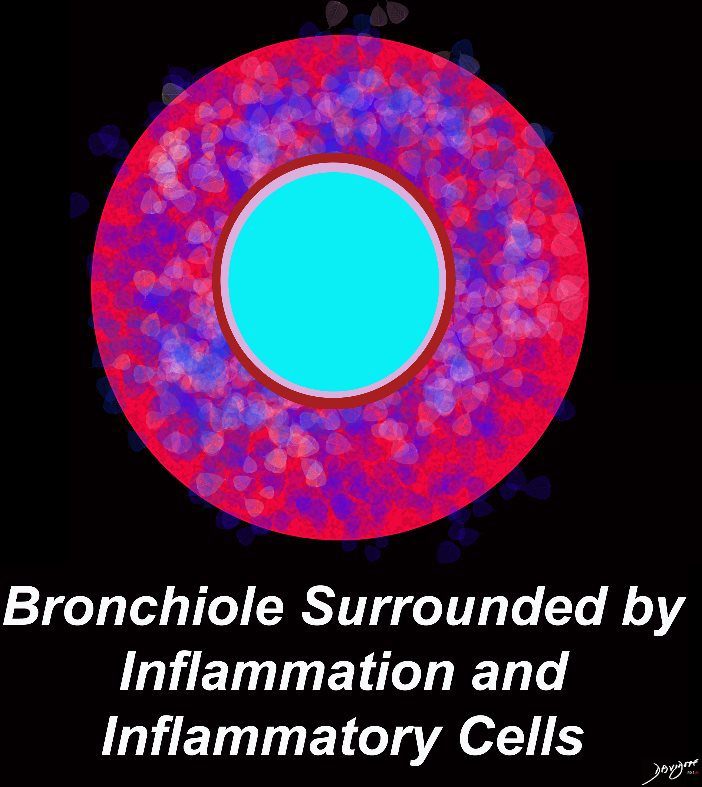

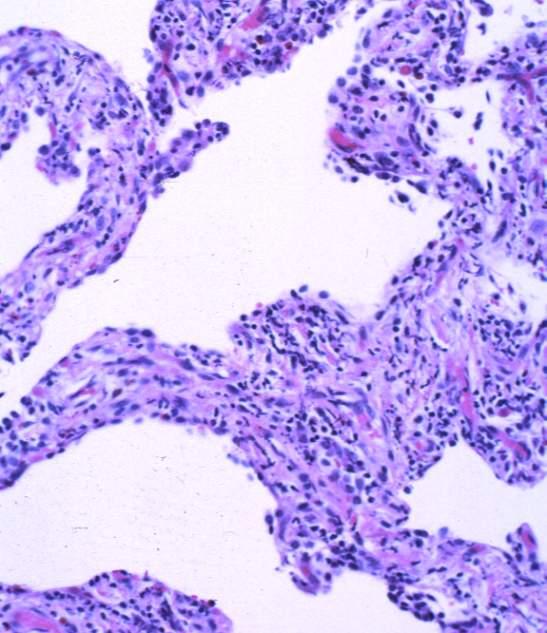

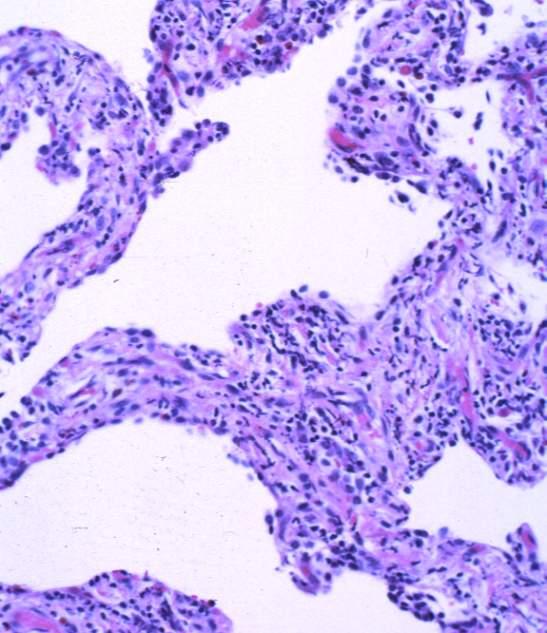

Anatomically

- Asbestosis is the scarring of lung tissue

- small airways including the

- alveolar ducts

- alveolar walls

- cause activation of the lungs

- immune system

- dominated by lung macrophages

- and provoke an

- inflammatory reaction

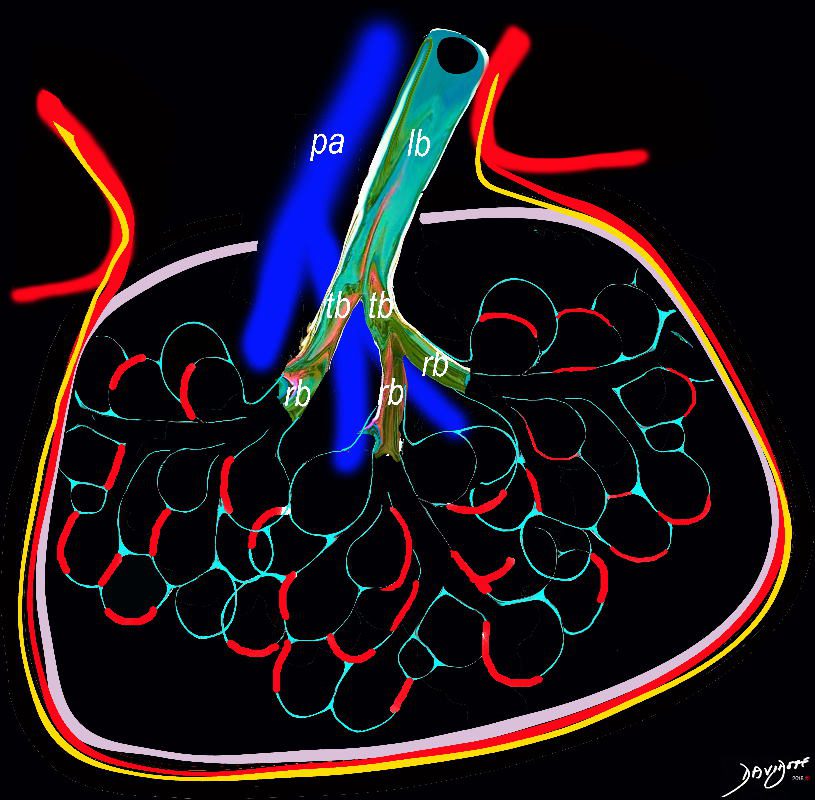

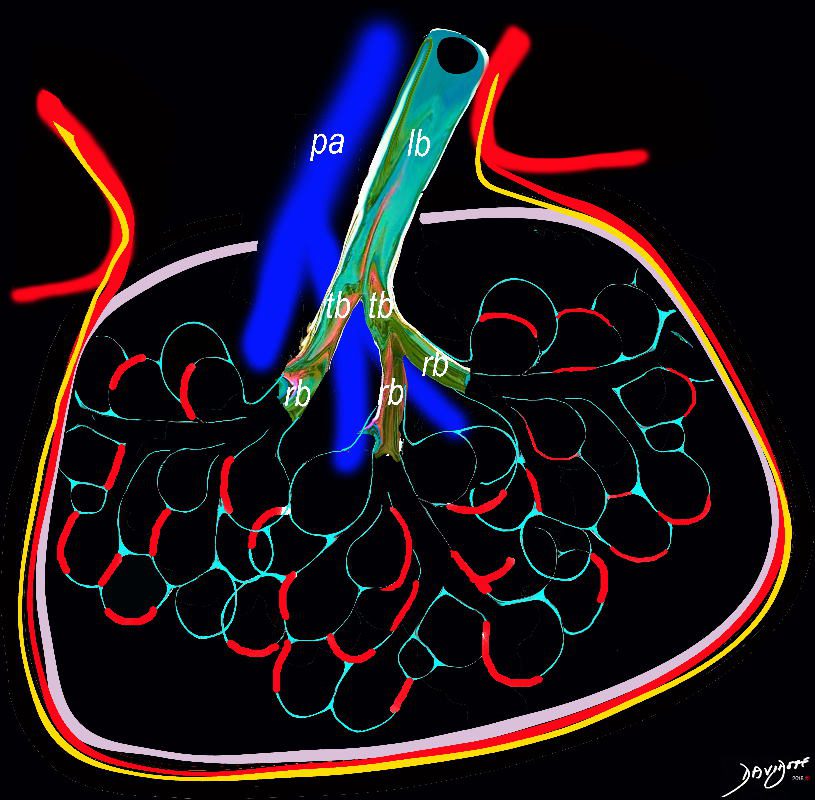

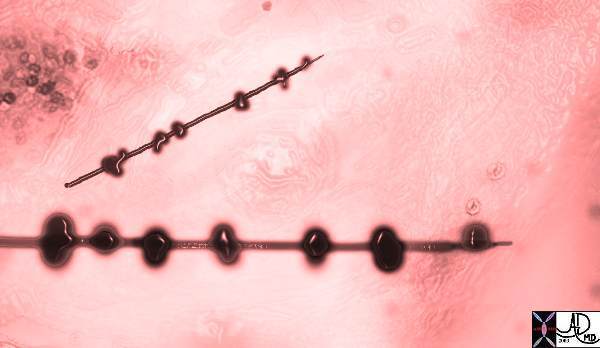

The diagram allows us to understand the the components and the position of the small airways starting in (a) which is a secondary lobule that is fed by a lobular bronchiole(lb) which enters into the secondary lobule and divides into terminal bronchioles (tb) which is the distal part of the conducting airways, and at a diameter of 2mm or less . It divides into the respiratory bronchiole (rb) a transitional airway which then advances into the alveolar ducts(ad) and alveolar sacs (as) Diseases isolated to the small airways do not affect the alveoli and hence there is peripheral sparing Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net lungs-0722

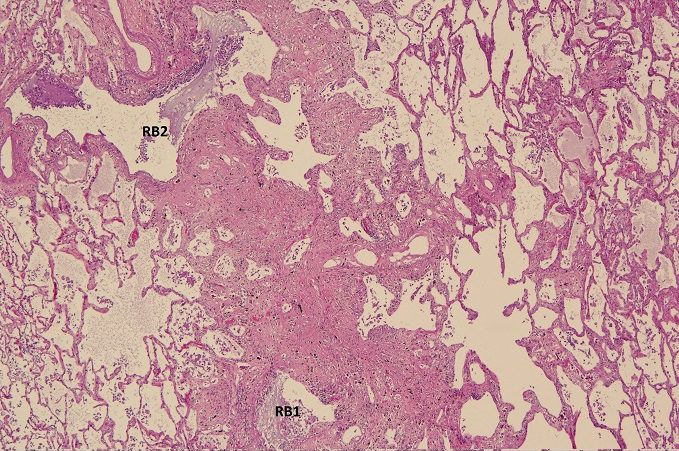

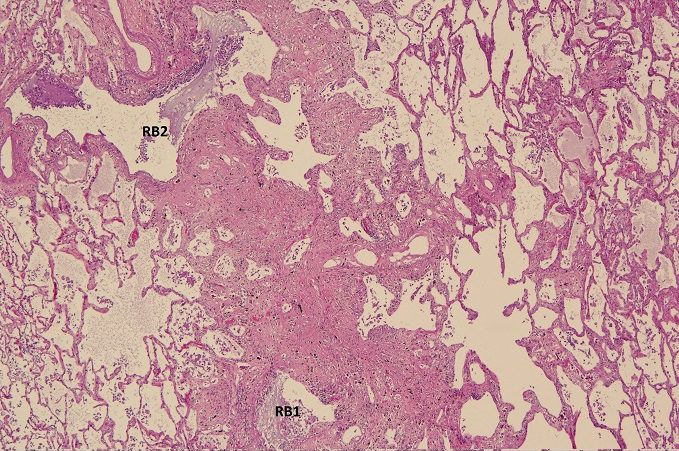

Peribronchiolar disease

Courtesy CDC

Penetrates the Interalveolar Septa

Ashley Davidoff TheCommonVein.net lungs-0736a01

Courtesy CDC

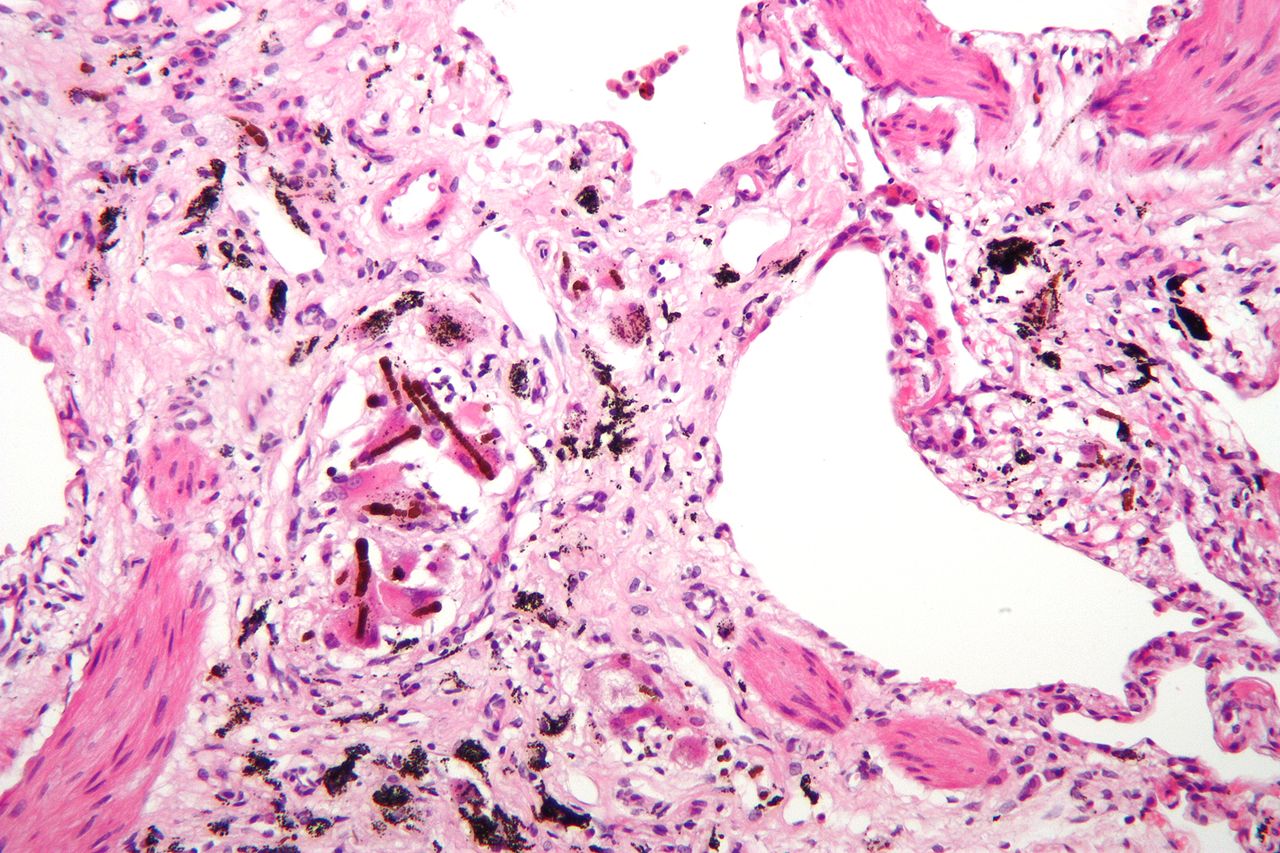

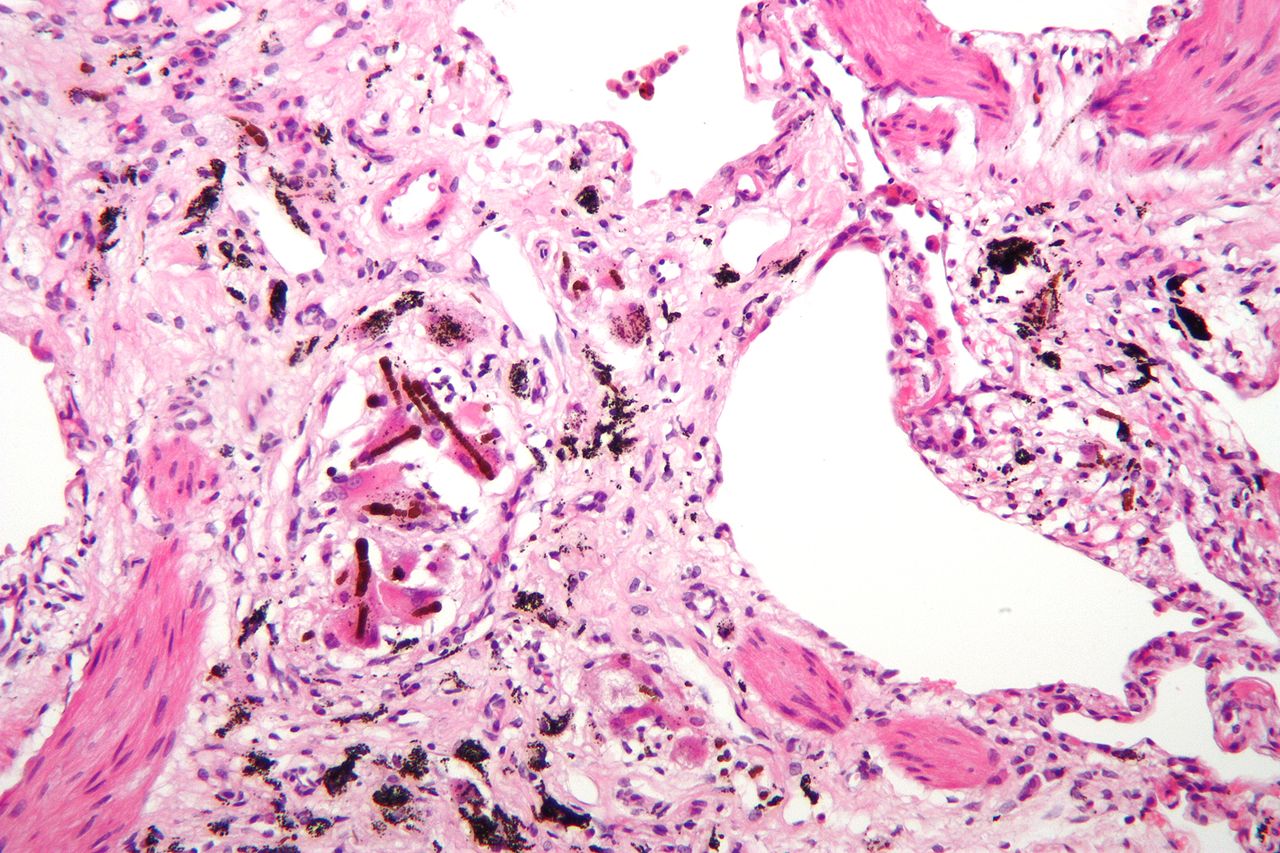

Courtesy Nephron –

Keywords:

lung pulmonary normal alveolus alveoli interalveolar septa thickened interstitium chronic inflammation asbestos UIP thickened histopathology

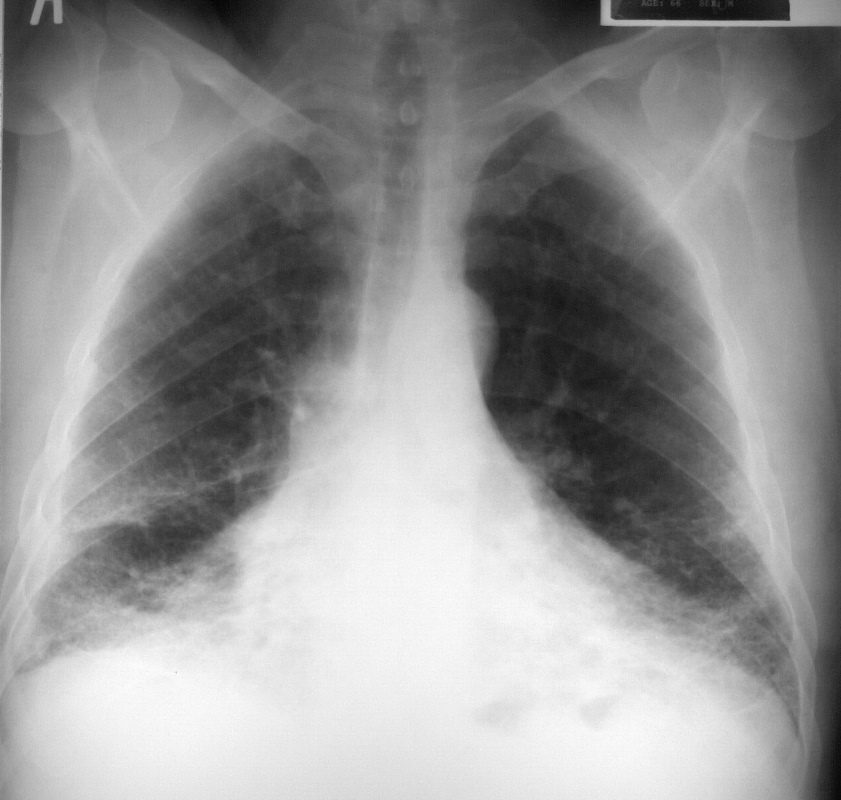

CXR

- Reticular opacities

- linear or branching opacities

- ground-glass opacities

- irregular or nodular opacities

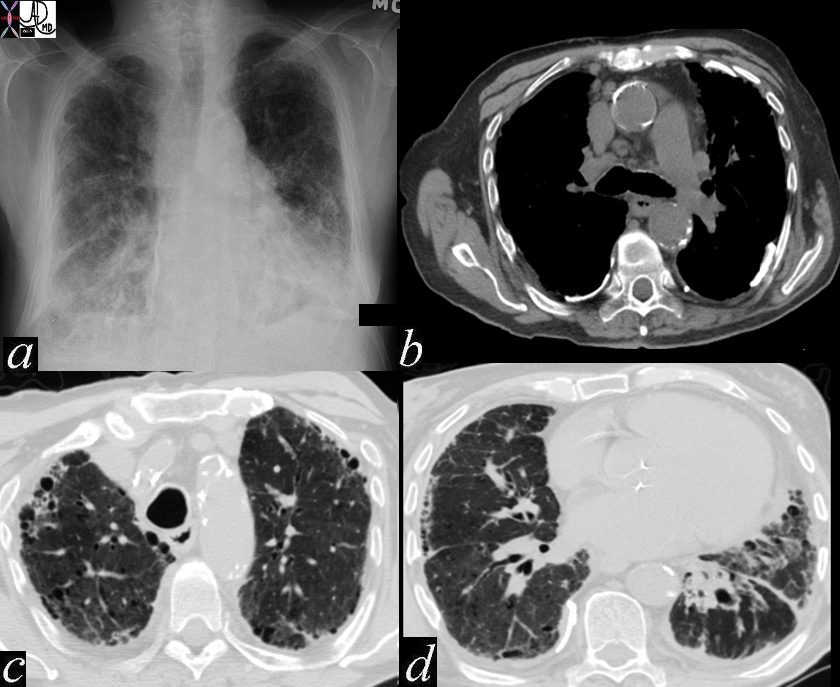

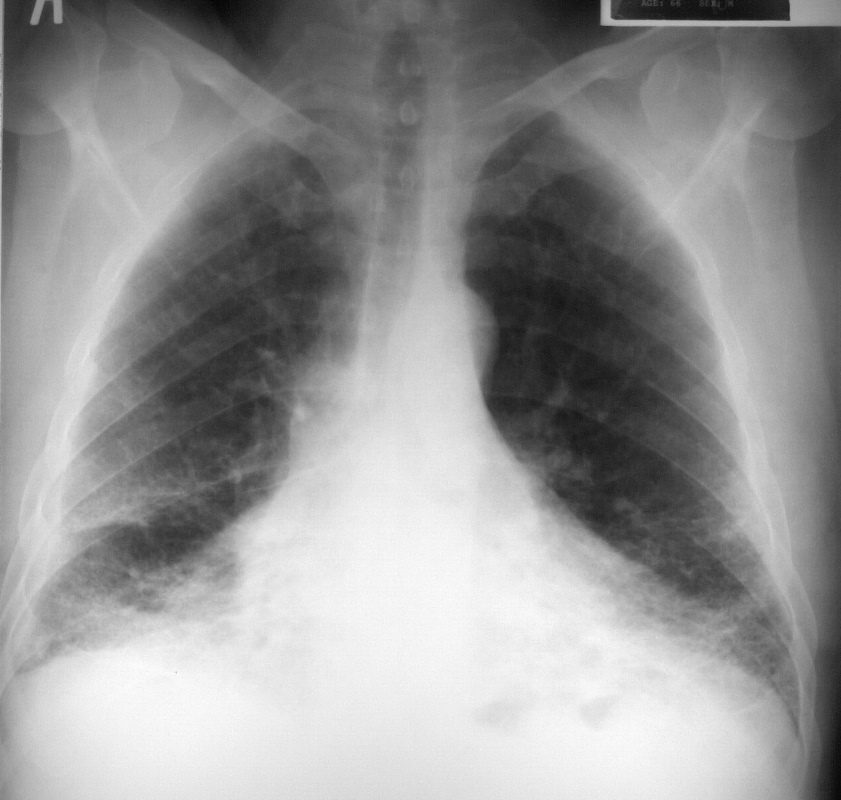

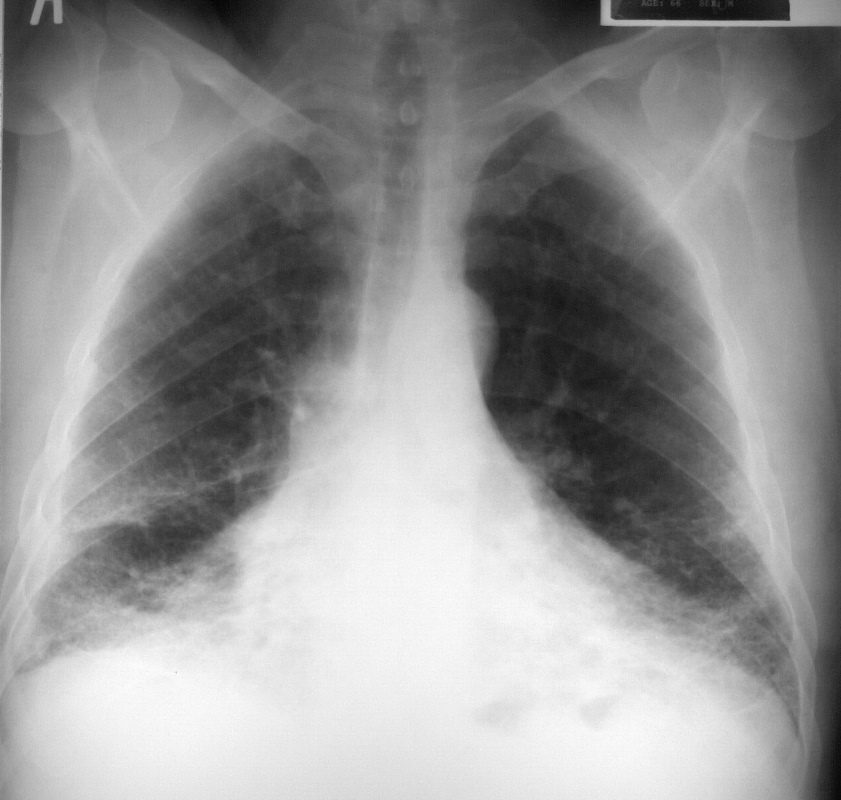

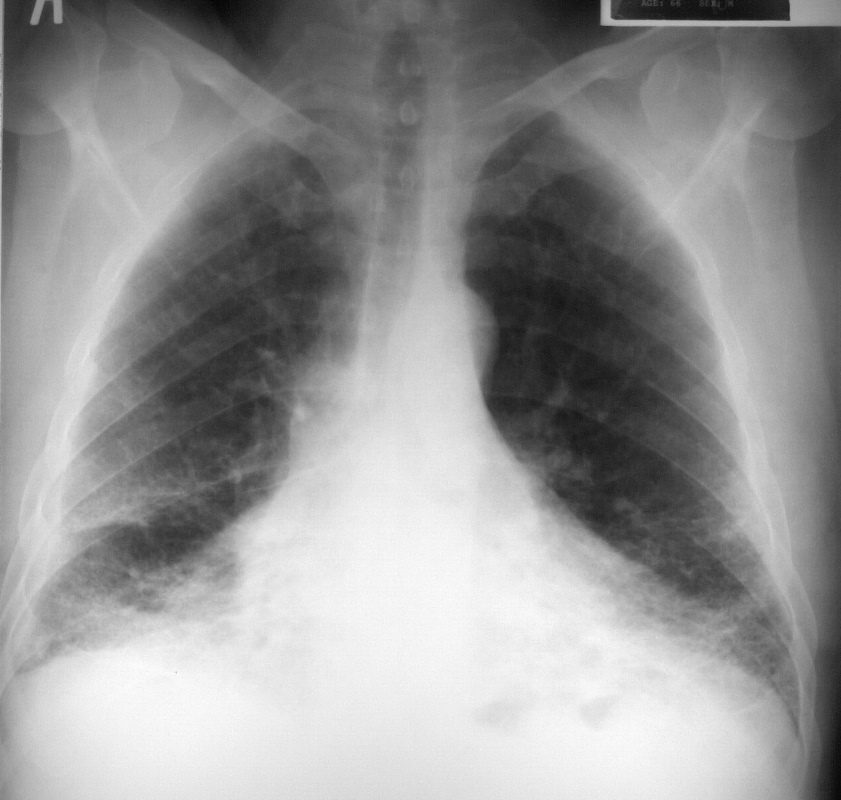

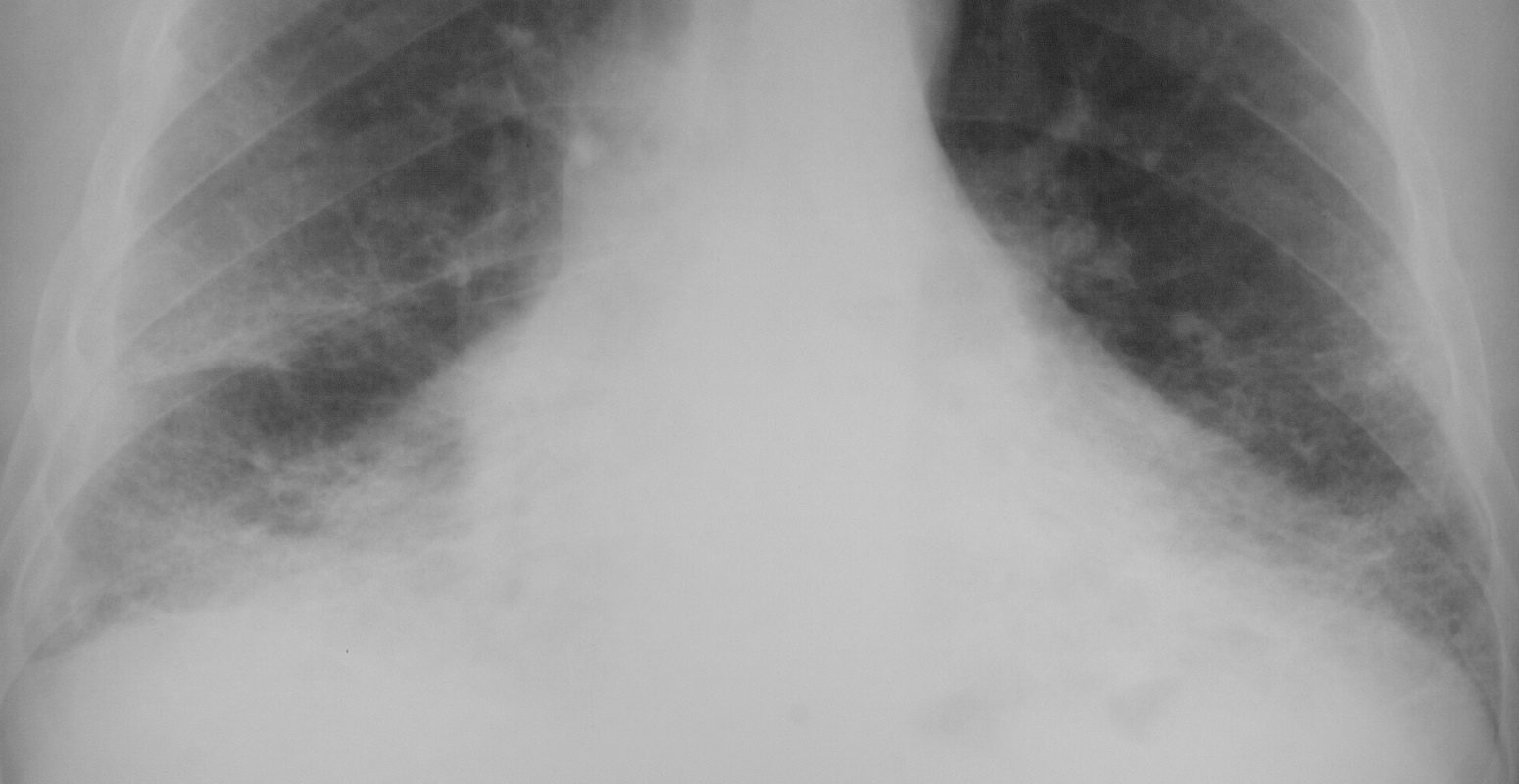

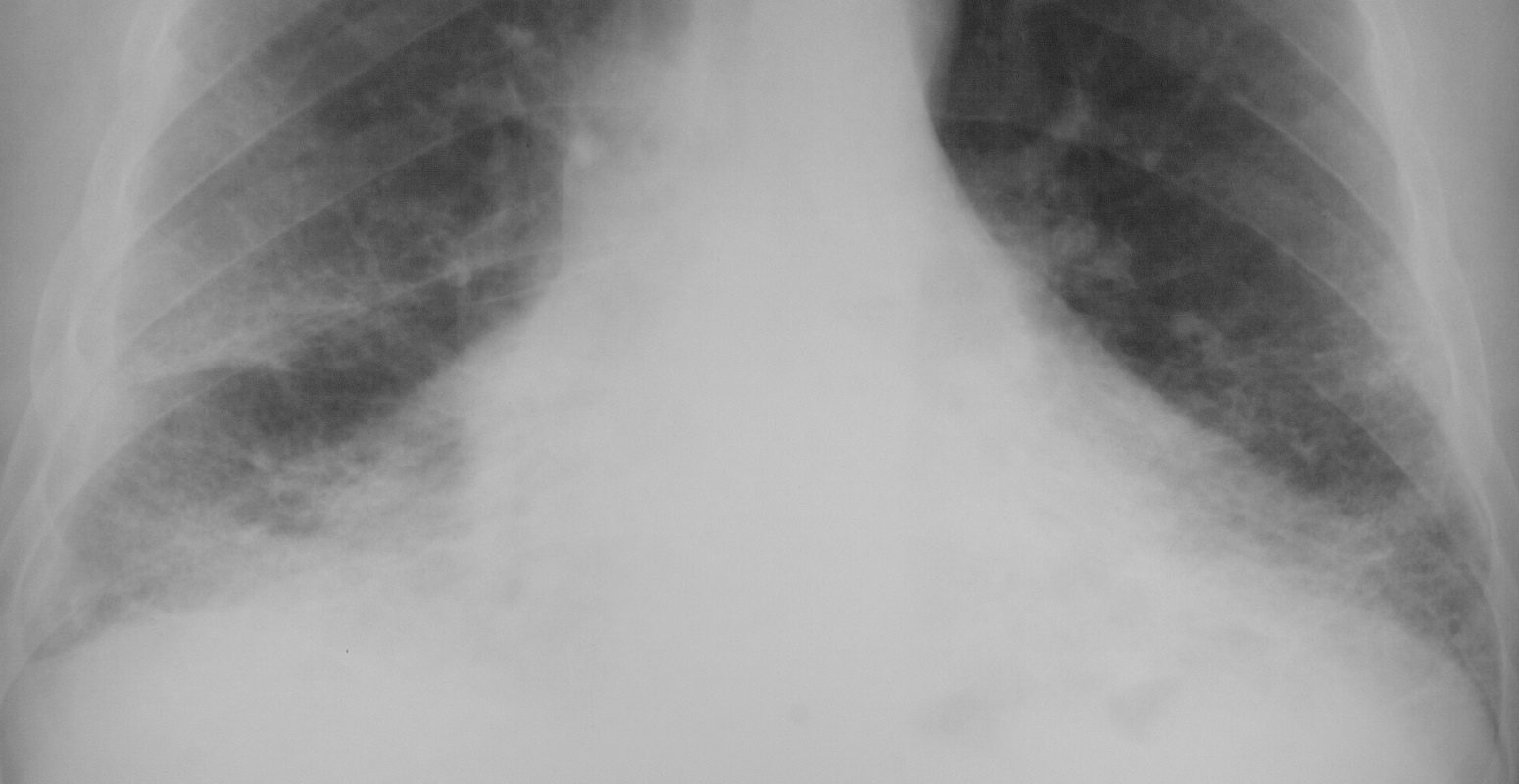

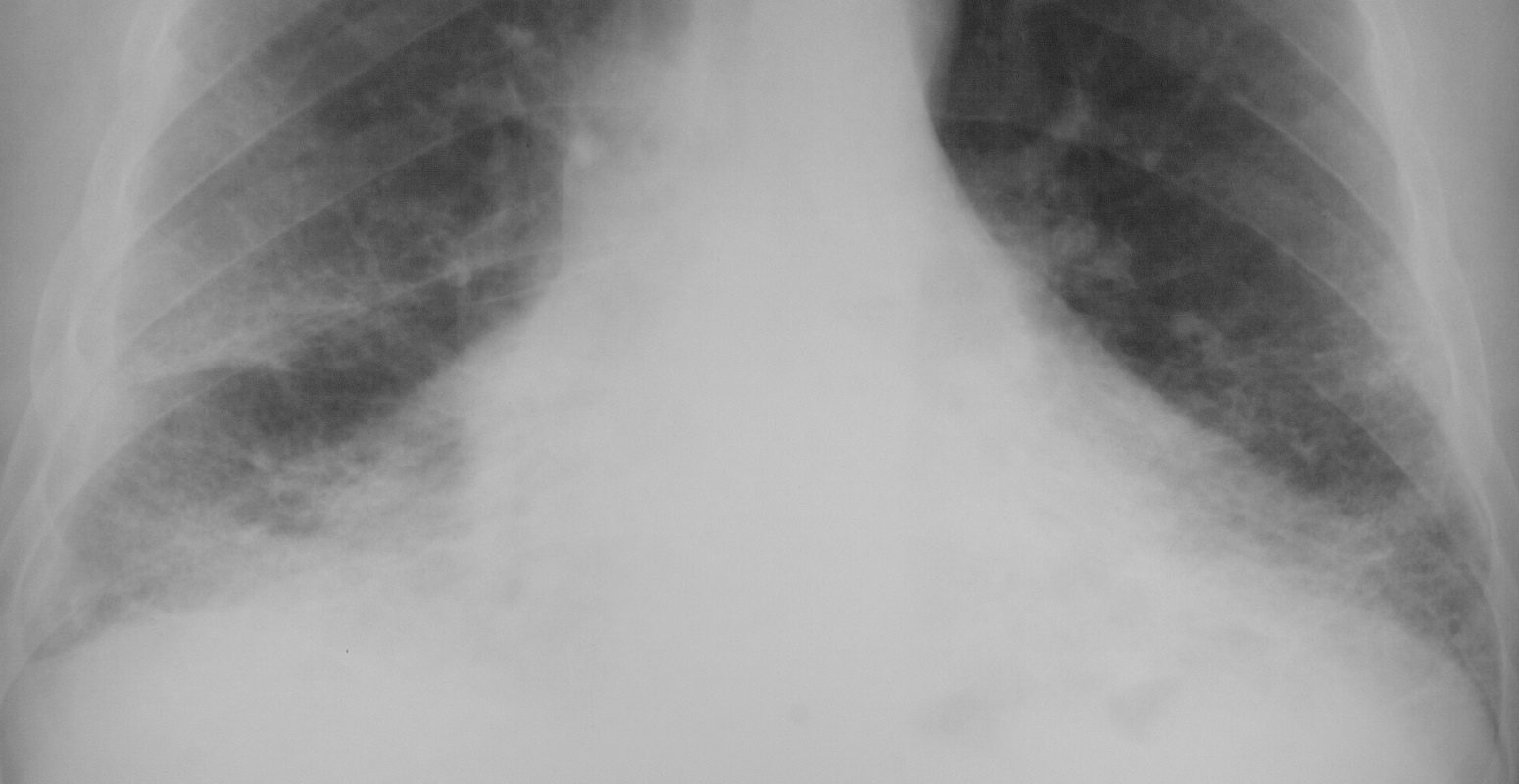

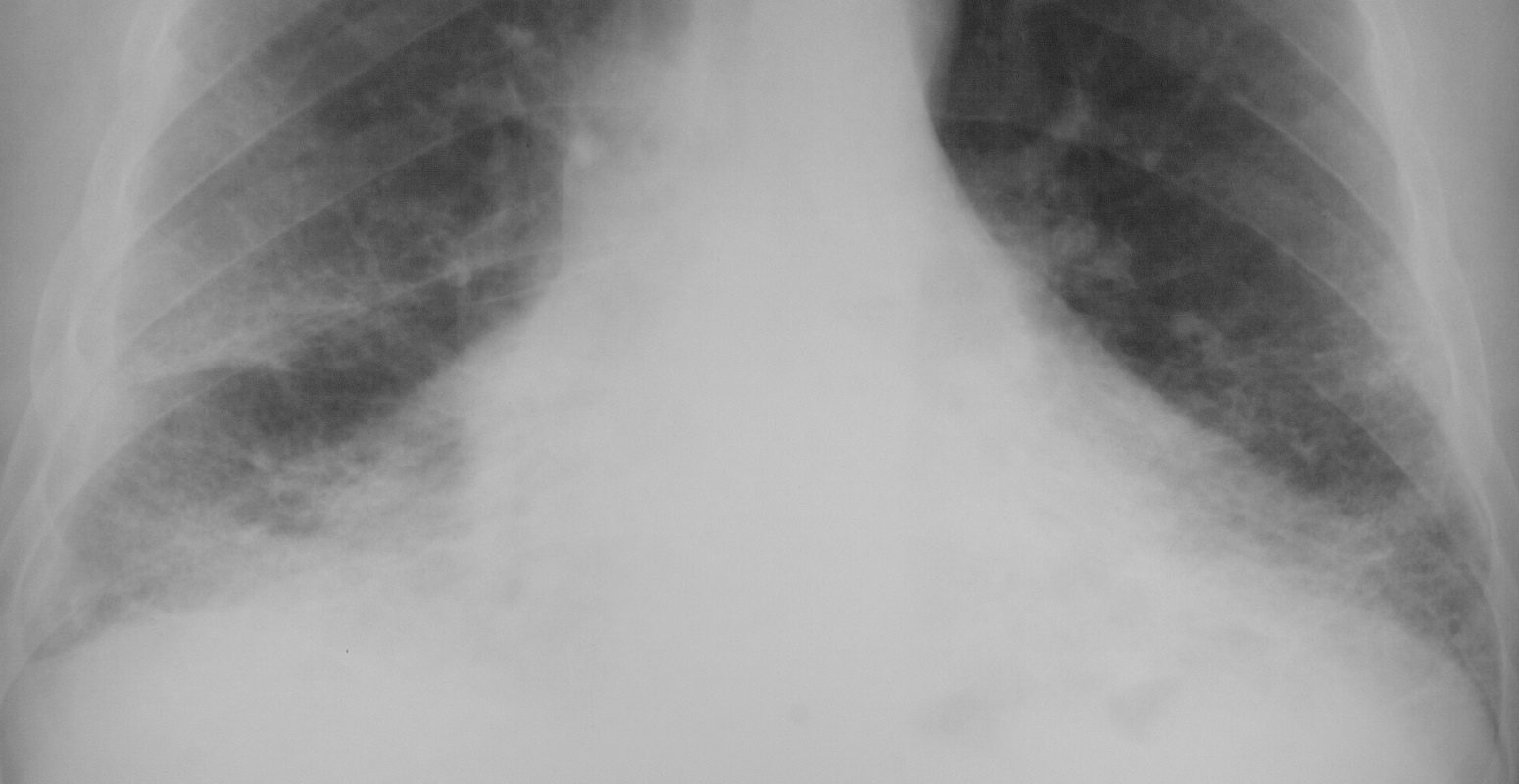

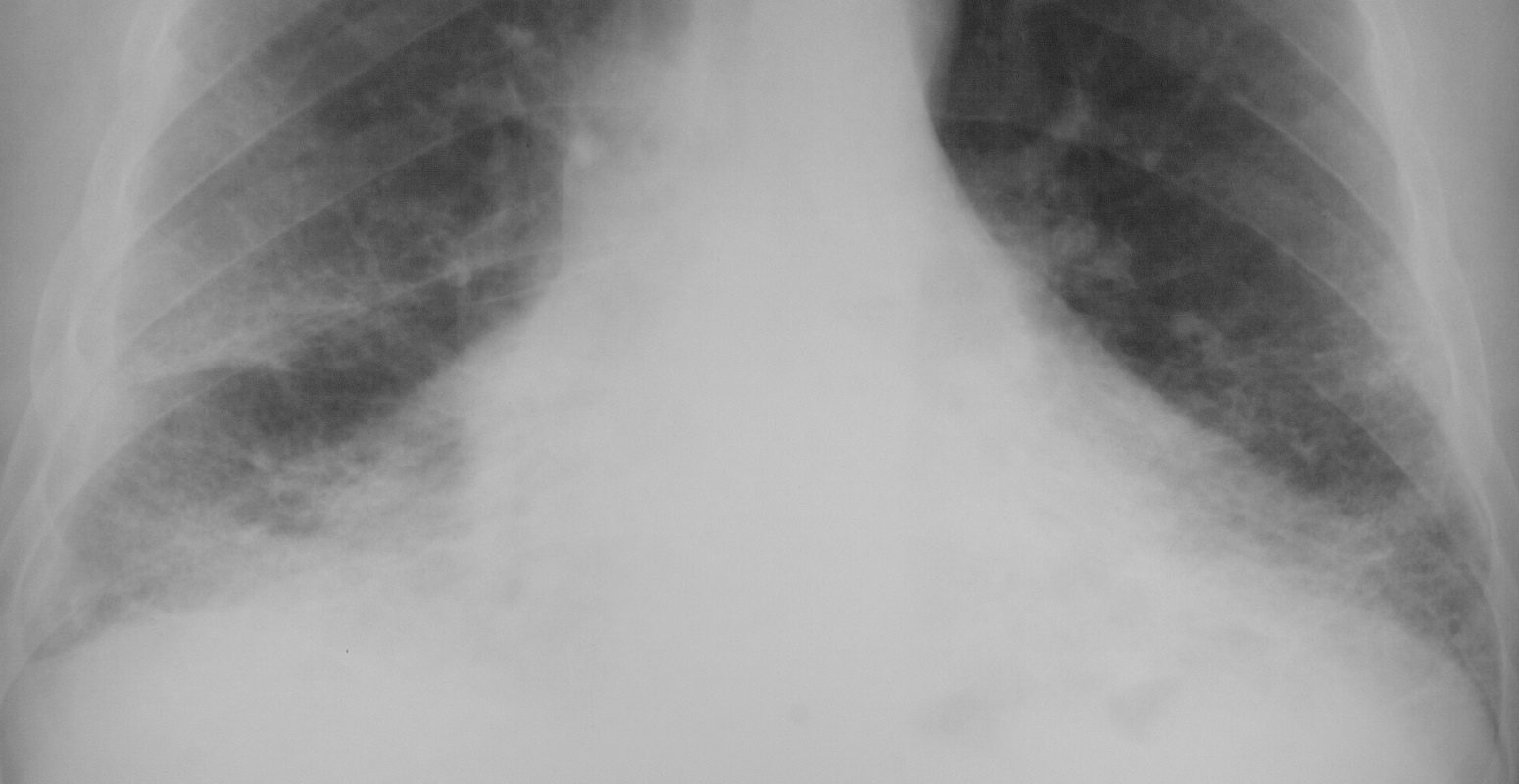

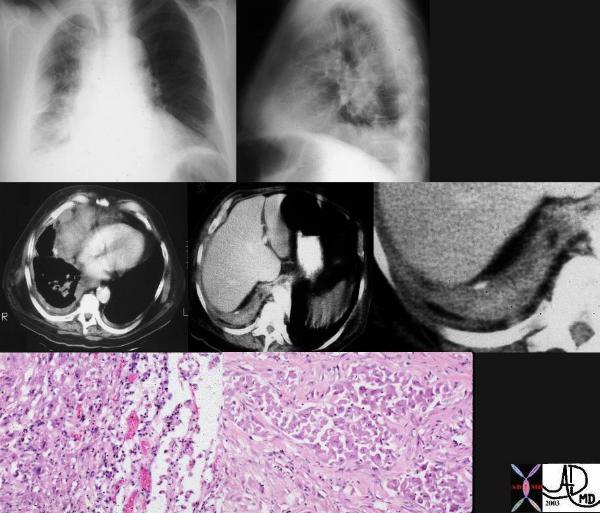

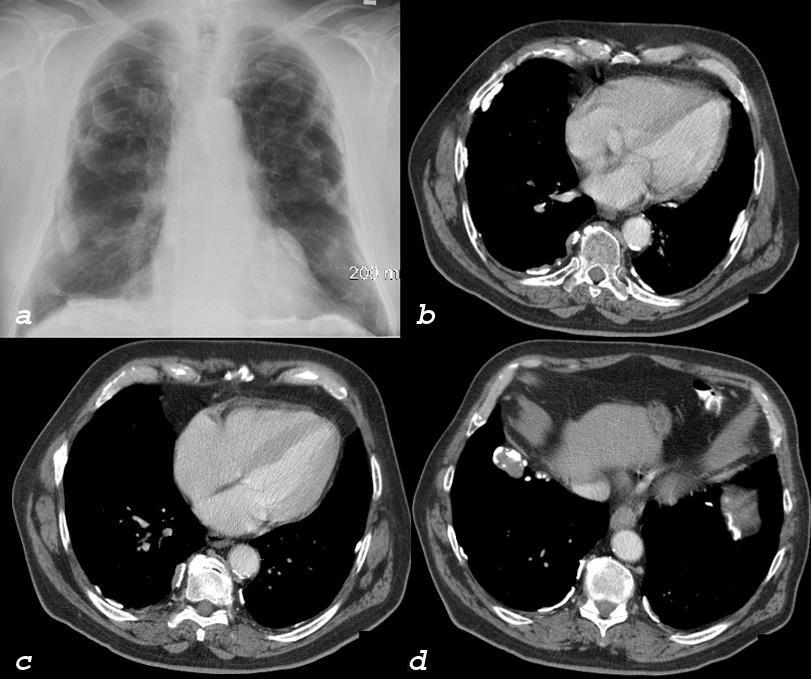

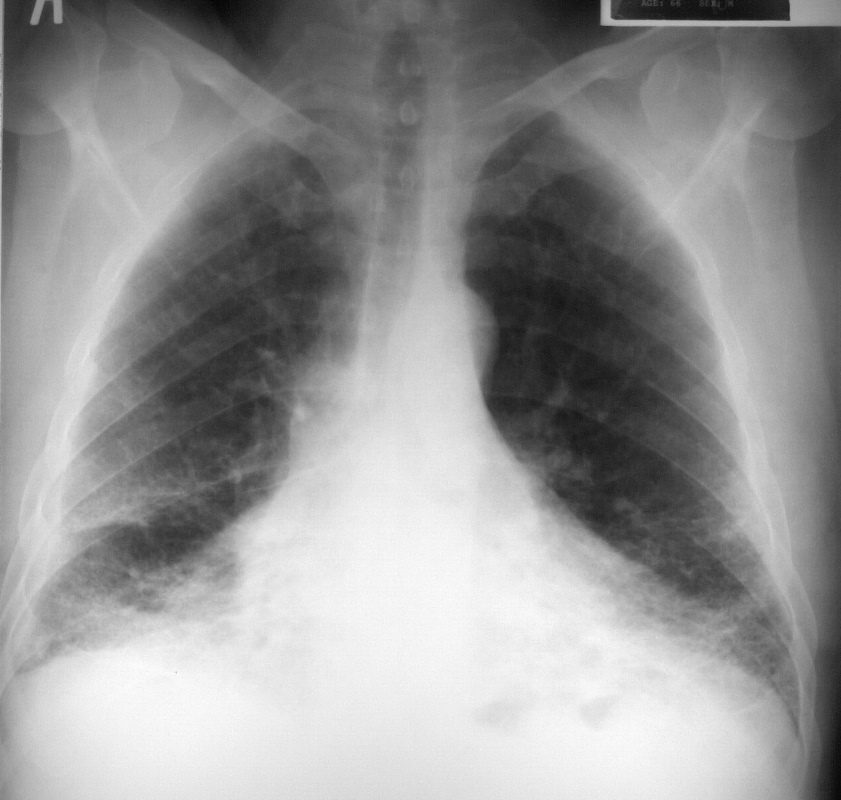

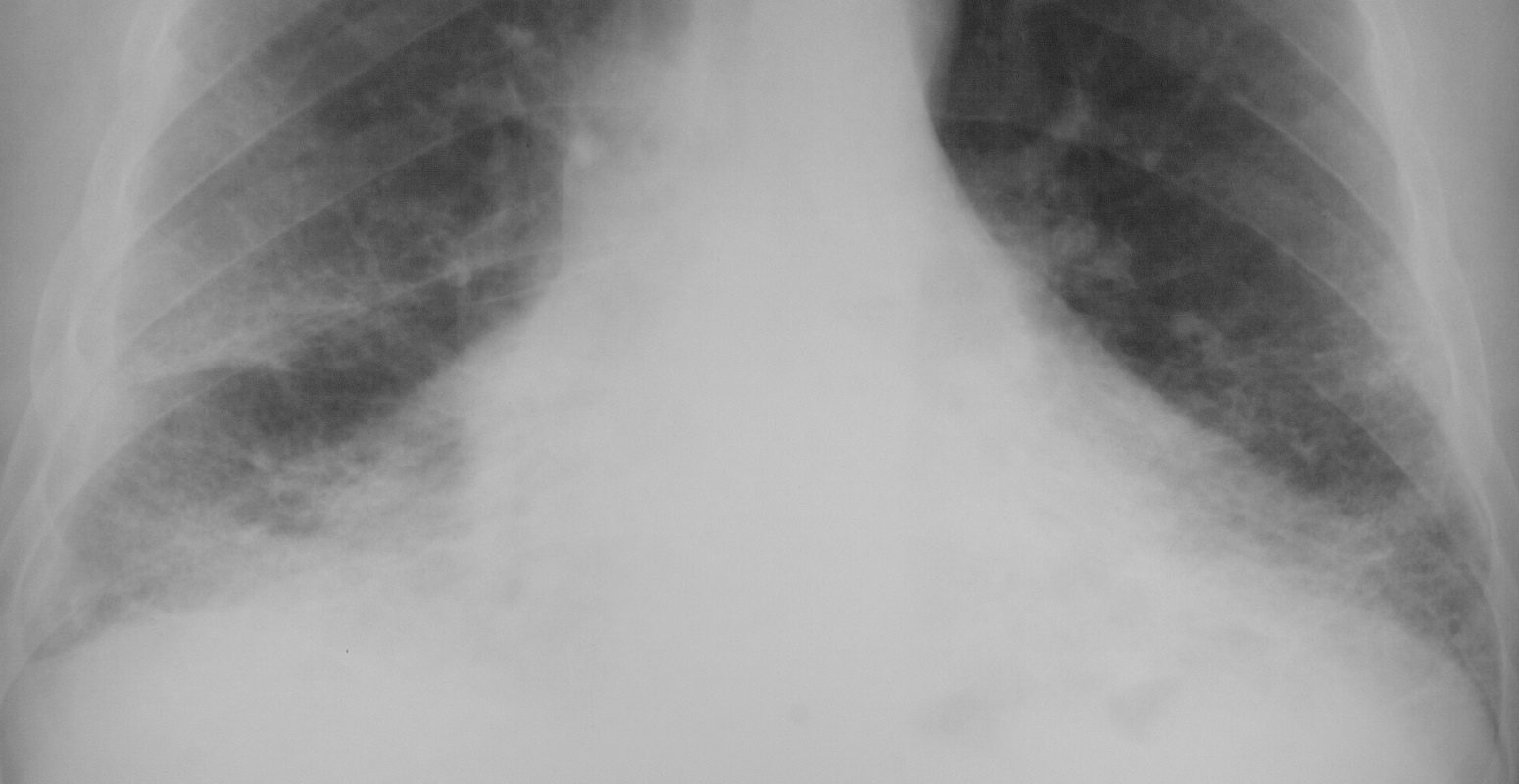

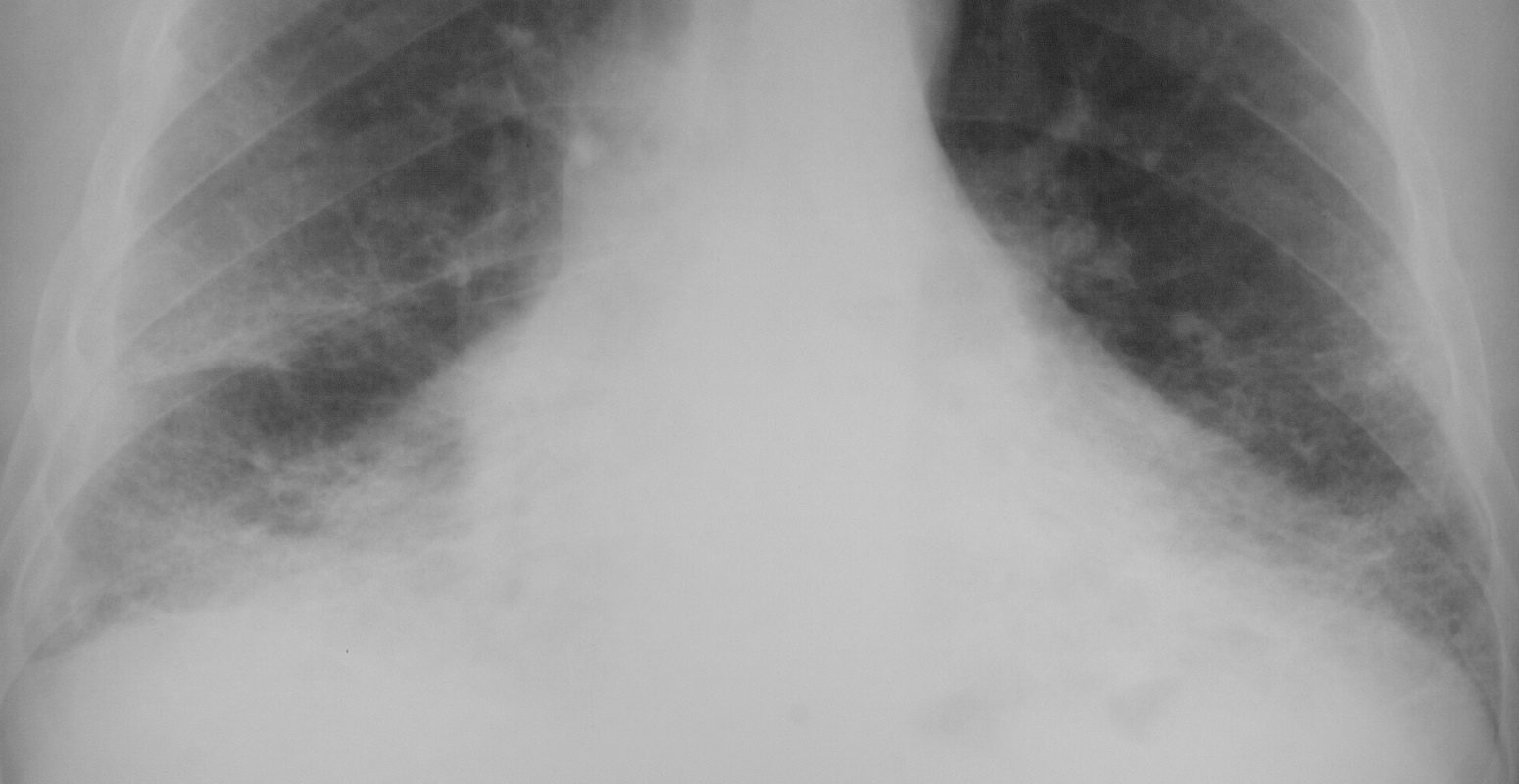

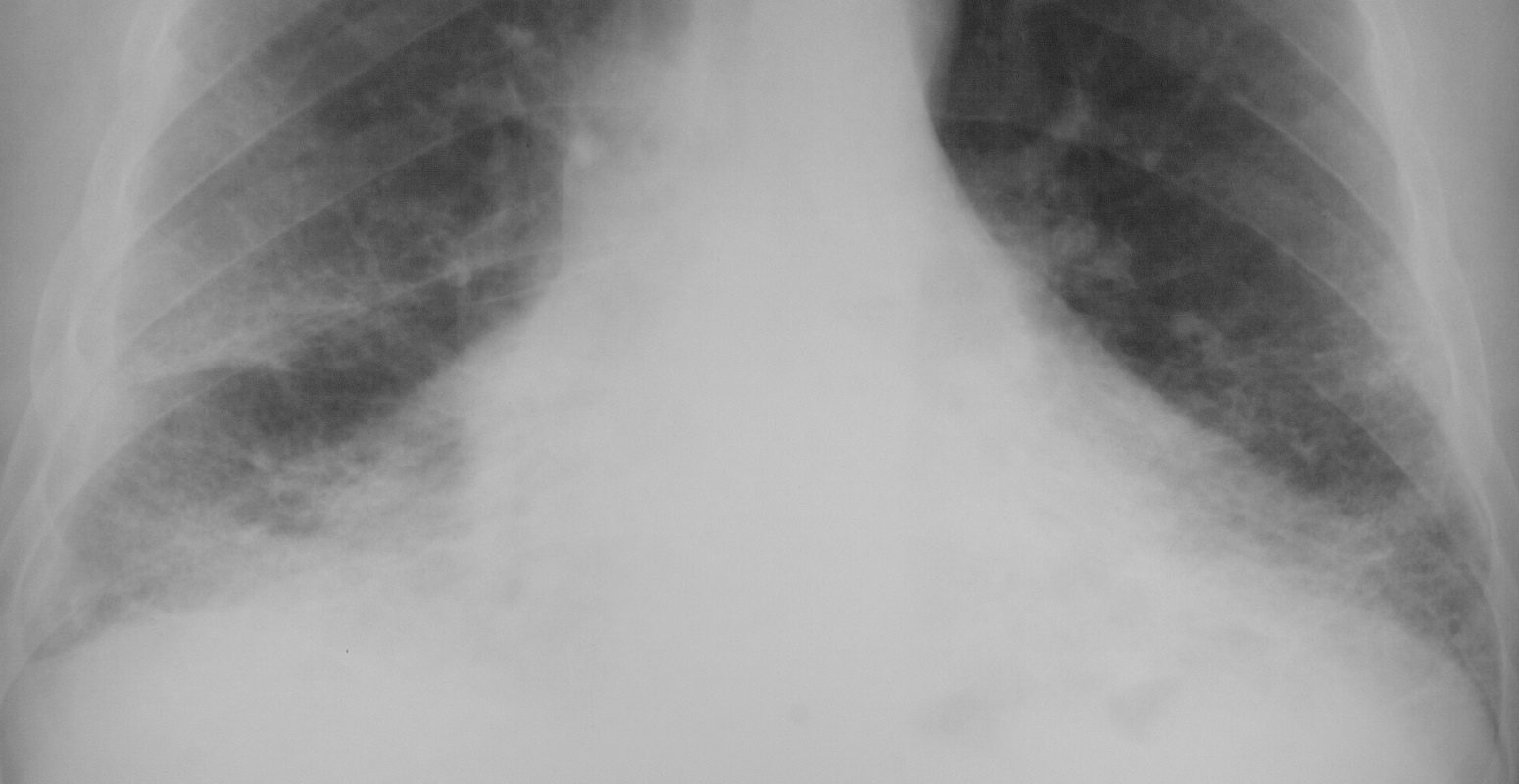

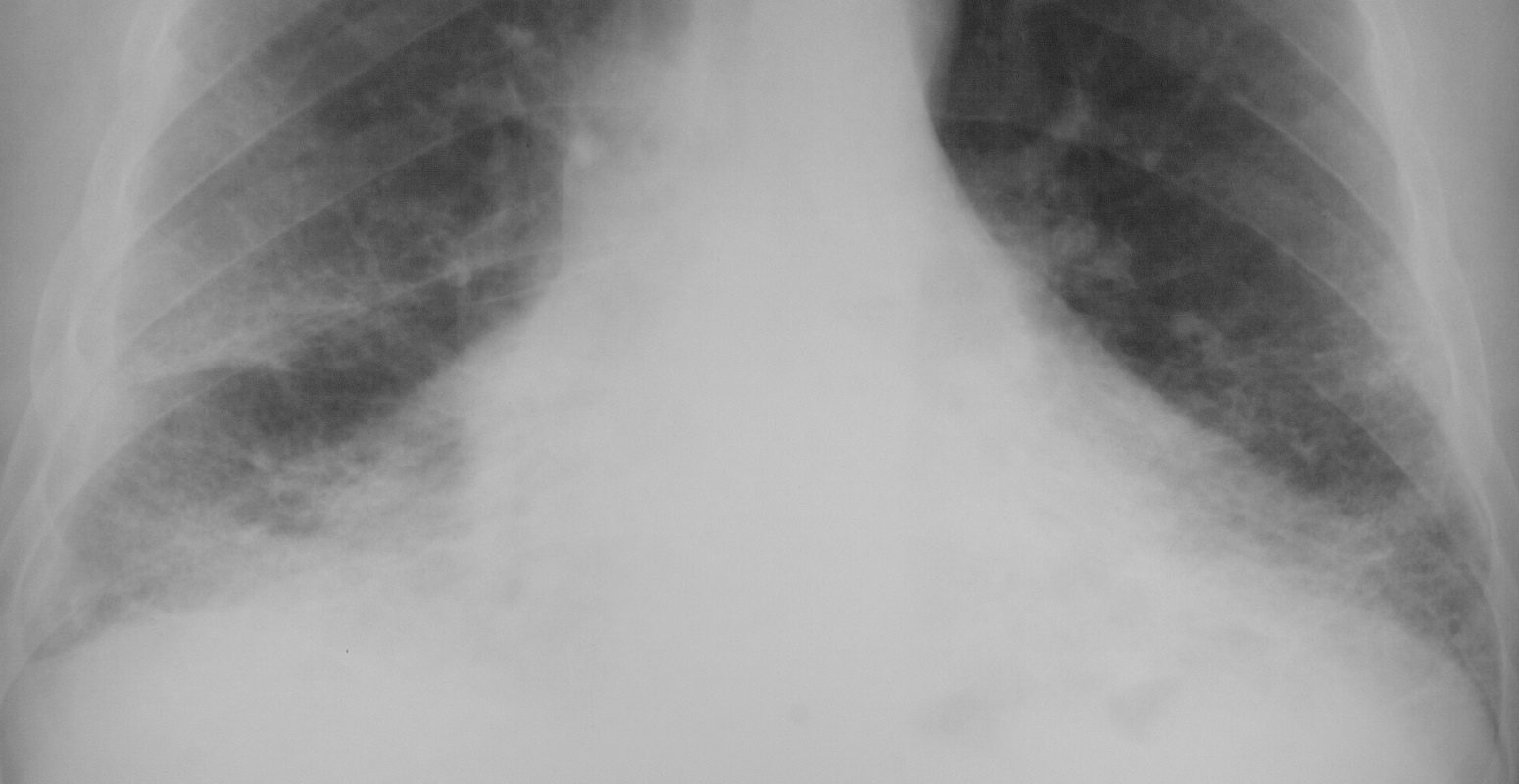

This is a frontal chest X-ray of a 66year old man who swept asbestos fibers off the floor for many years. The image characterises the “shaggy heart border” due to the interstitial process in the middle lobe lingula and lower lobes.

Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD 2019

32615.8

Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD 32617.8

Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net 32617.8

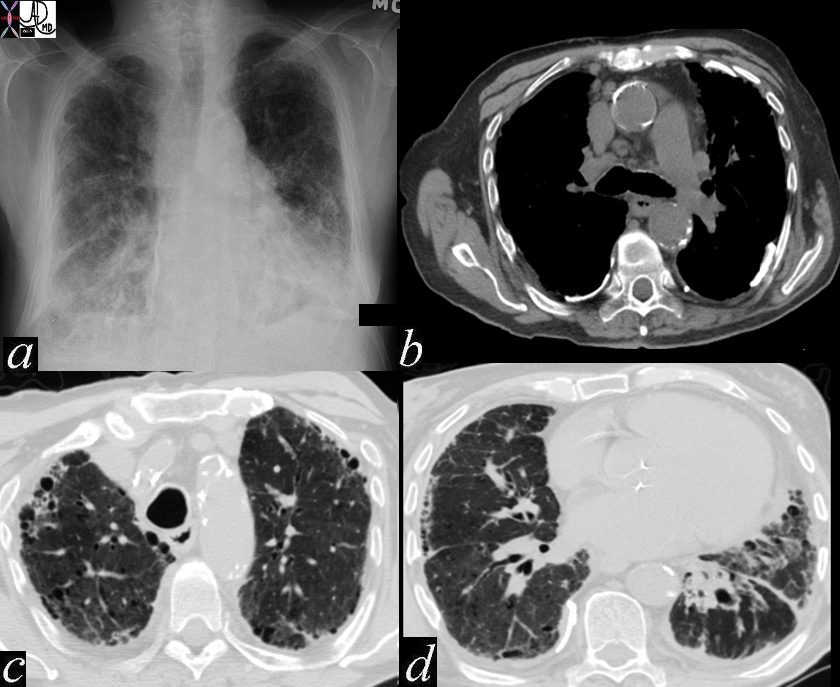

CT

- subpleural linear densities;

- interlobular septal thickening;

- centrilobular thickening;

- subpleural parenchymal bands

Ashley Davidoff MD thecommonvein.net 47060c01

keywords chest lung fx shaggy heart border reticular changes interstitial lung disease interstitium honeycombing pleural calcification fibrosis dx asbestosis

Introduction

Asbestos derived from the Greek, meaning “inextinguishable” or “unquenchable”.

It is a collective term for a group of of fibrous mineral silicates of the serpentine and amphibole groups that break into fibers when crushed rather than into dust They are heat and acid -resistant minerals.

Asbestos is a group of naturally-occurring minerals, such as chrysotile, amosite, and crocidolite. It is often used for insulation and in other building aspects. When these microscopic bundles of fibers are inhaled into the lungs, they can cause health problems such as asbestosis, mesothelioma, and cancer. Asbestos is a is a mineral that is as soft and flexible as cotton, yet it is fireproof.

The generic name “asbestos” belongs to a group of minerals called “asbestiform” minerals. Asbestos is a fibrous material which is mined from serpentine rock. Basically, rock was mined and crushed. When the rock was crushed, fibrous stands of asbestos were extracted from the rock. The strands where put in bags and shipped to manufacturing facilities were the asbestos was used as an ingredient in insulation and other materials. The three most commonly used forms of asbestos in product manufacturing were chrysotile, amosite and crocidolite.

Although asbestos products have not been used in construction since approximately 1975, the products in place present a clear danger to individuals involved in repair work and the demolition of structures containing asbestos products

|

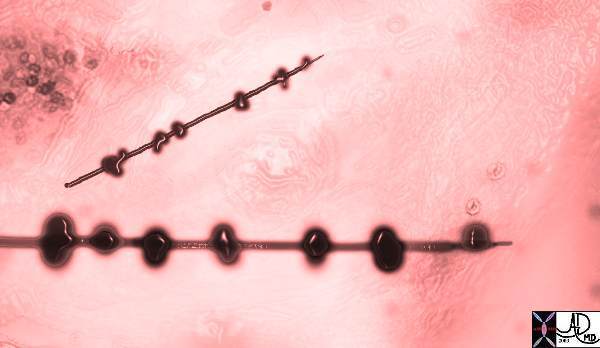

Asbestos bodies – an artistic impression Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD. 32697

Asbestosis

Asbestosis is a disease characterized by the signs and symptoms associated with the inhalation of asbestos particles. Asbestosis is the most common occupational lung disease among the inorganic dust-related chronic pulmonary conditions. Asbestos and asbestos related products were widely used for thermal and electric insulation as well an in the mining and construction industries.

Starting on the 1940’s asbestos products including the serpentine (chrysotile) and the amphiboles (i.e., crocidolite, amosite, tremolite, anthophyllite) were widely used in all previously mentioned fields of the industry until the 1970’s when it was mostly replaced with synthetic mineral fibers. Nowadays the field most at risk for asbestos exposure is the demolition industry. Asbestos use is now better regulated in developed countries but continues to be a threat to the health of working populations in less-developed countries where its use is poorly regulated.

Exposure to these mineral silicates was not limited to people dealing directly with the material. Although less frequently, there are cases of asbestosis correlated with moderate exposure as with second hand exposure due to sharing of the same work place or exposure to clothing of workers dealing with asbestos.

After asbestos exposure (usually for more than 10 years) the lungs may show a restrictive pattern which means that there is a decrease in lung volumes due to fibrosis. The degree of fibrosis is correlated with the intensity and duration of exposure.

Principles

Three types

blue (crocidolite), brown (amosite) and white (chrysotile

induces fibrosis in the interstitium

lower lung fields

follows a loss of elasticity in the lung tissue

The first lesions found in asbestosis are identified in the alveolar ducts and peribronchiolar regions (small airways). Deposited asbestos fibers attract alveolar macrophages which in turn induce the inflammatory and fibrotic lesions in the lungs.

Honeycombing occurs in the most extreme cases of the disease where there is extensive fibrosis and the lungs present small and stiff.

Historical Aspects

B.C.

The Greek geographer Strabo, and Pliny The Elder, Roman Historian, observed lung disease in slaves who wove asbestos into cloth. It was called “disease of slaves.” Pliny refers to the use of a transparent bladder skin as a respirator to avoid inhalation of dust by slaves.

1877

First Asbestos Mine opened in Canada

1882

Keasby & Mattison conceives idea of using heat resisting asbestos fibers as reinforcement agent in 85% magnesia pipe insulation.

1897

Jones reports that in New York, there were “hundreds of buildings plastered with asbestic.” “Asbestos and Asbestic”, J. Soc. Arts.

1918

Asbestosis reported in marine fireman, Pancost & Miller, Am. J. Roentgenol.

1924

Cooke reports death of young woman in a British asbestos factory due to “pulmonary asbestosis.”

1927, a foreman in an asbestos textile plant in Massachusetts filed the first workers’ compensation disability claim for asbestosis.

1928

Article entitled “Pulmonary Asbestosis” appears in Asbestos Magazine, a trade journal for the asbestos industry.

1929

Haddo reports case of asbestosis in person living next door to an asbestos factory.

1930

First U.S. autopsy established the existence of asbestos lung disease on this side of the Atlantic.

Chief Surgeon of U.S. Bureau of Mines reports case of asbestosis in a man who had been exposed to asbestos while doing maintenance work in a government hospital. The maintenance worker received compensation for his asbestosis. Wilcox, Proceedings of Conf. Re Effects of Dusts upon Respir. System. Wisconsin (1932).

1931

Great Britain enacts laws to regulate asbestos exposure levels for plant workers.

1932

Encyclopedia Britannica identifies asbestos fibers as a cause of lung cancer.

1932

Concerns raised about potential for disease among office workers and commuters in buildings and tunnels where sprayed on asbestos materials were present. Lancet and McLaughlin, Lancet (1953).

1934

Ellman reports asbestosis in an insulation worker. Br. J. Radiol.

1935

Lynch and Smith report cases of asbestosis and lung cancer in American Journal of Cancer. As little as 19 months exposure. Gloyne also reports asbestosis-cancer deaths in Tubercle.

1942

Holleb and Angrist report two cases of bronchogenic carcinoma associated with asbestosis. Am. J. Pathol.

1944

Hutchinson warns of asbestos risk in U.S. industrial journal for construction workers. Heating and Ventilating.

1944

Editorial in Journal of American Medical Association linking asbestos and lung cancer

1946

Eight (8) cases of asbestosis and lung cancer in insulator by Chief Inspector of Factories.

1947

Pleural mesothelioma reported in an insulator. New Engl J. Med.

1949

Annual Report of the Chief Inspector of Factories for the Year 1947, Great Britain, reports survey of asbestos related cancer deaths in English asbestos factories. Warns of need for dust control among construction workers.

1951

Stoll, Bass and Angrist report case of lung cancer and asbestosis in insulator and emphasized “the hazards of industrial exposure…. and need for preventive measures.” Arch. Int. Med.

1954

Steamfitters, plumbers and pipefitters identified as potentially hazardous trade because of asbestosis and lung cancer in California. Authors suggest further studies. Breslow et al, Am. J. Publ. Health.

1955

Doll reports on Mortality from Lung Cancer in Asbestos Workers. Br. J.Indust. Med. Doll observed 113 factory workers between 1935 and 1953 and reported 39 deaths.

1956

Chief Inspector of Factories in Great Britain calls attention to hazards of asbestos cement work, demolition and with breaking of sacks of asbestos cements. Annual Rept. Of Chf.. Insp. Of Factories.

1962

Pleural mesotheliomas reported in long time shipyard workers. McCaughey, Br. Med. J.

1930 Second article bearing same name appears in Asbestos Magazine.

1929-1931 Metropolitan Life Insurance Company (“Met Life”) conducts industrial hygiene surveys of Johns-Manville Corporation and Raybestos-Manhattan Corporation facilities.

1934 Met Life study, entitled “Effects of Inhalation of Asbestos Dust on the Lungs of Asbestos Workers” reports that prolonged exposure to asbestos dust causes pulmonary fibrosis and that asbestosis could in severe cases, be fatal.

1941 Asbestos Textile Institute (“ATI”), a trade association of producers of asbestos-containing cloth, is formed.

1941 Industry sponsored medical research in Saranac Lake, New York demonstrates health hazards of asbestos.

1940’s ATI documents reflect frequent

1950’s Discussions and presentations pertaining to appropriate medical practices and to the funding of a study to possibly refute reports of the asbestos/cancer link.

1942 Manufacturer of asbestos insulation products compiles its “weapon in reserve”, over 600 pages of medical articles about the dangers of asbestos.

1943 Saranac Lake scientists inform asbestos insulation manufacturers that their products “have the makings of a first-class hazard”.

1940’s Despite this knowledge, asbestos industry continues to manufacture and sell asbestos insulation products.

1957 ATI decides to reject asbestos/cancer study because it would serve only to “stir up a hornet’s nest and put the whole industry under suspicion”.

1958 Published version of Quebec Asbestos Mining Association report concludes that asbestos miners did not suffer from higher incidence of lung cancer than did general population. Unpublished version, concealed by asbestos industry, shows that opposite is true

Classification

Asbestosis is a diffuse interstitial disease. It can be classified on the basis of its forms. It is the form of asbestosis that determines whether the disease occurs.

Asbestose primarily has two forms: The serpentine form which has curly and flexible fibers or the amphibole form which has straight and brittle fibers.

The amphibole form has a greater pathogenicity. Though both the forms increase fibrosis in the lung, the amphibole form is also linked to mesotheliomas.

Statistics

It has been estimated that over 25 million people have been exposed to asbestos in the past 40 years. In 1992, there were 959 deaths from asbestosis.

White: 898 (93.6%)

Black: 57 (5.9%)

Other: 4 (0.4%)

Geographic Considerations

Asbestos minerals:

– Serpentine

Chrysotile (white asbestos)

Location of major deposits:

Canada (Quebec, British Columbia, Yukon, Newfoundland ), Russia, China (Szechwan), Brazil, Mediterranean countries (Cyprus, Corsica, Greece, Italy), southern Africa (South Africa, Zimbabwe, Swaziland)

Commercial use:

Asbestos cement products (pipes, gutters, tiles, roofing); insulation, fireproofing, reinforced plastics (fan blades, electric switchgear); textiles; friction materials; paper products; filters, spray-on products

– Amphibole

Crocidolite (blue asbestos)

Location of major deposits:

South Africa (Northwest Cape ), western Australia

Commercial use:

Used in combination, mostly in cement but also in many of the products listed above

Amosite (brown asbestos)

Location of major deposits:

South Africa (northern province, former Transvaal)

Anthophyllite

Location of major deposits:

Finland

Commercial use:

Filler in rubber and plastics

Tremolite (No commercial use)

Contaminates ore in certain asbestos, talc, iron, and vermiculite mines; also found in some agricultural soils

May or may not be removed in processing; has rural domestic uses (e.g., stucco)

Cummington-grunerite (No commercial use)

Contaminates ore in certain iron mines (often not fibrous

Population Groups

From 1991-1992 there were 578 deaths from asbestosis in studied states. The most frequently recorded occupations on death certificates of deceased from asbestosis were:

Plumbers, pipefitters, steamfitters: 46

Electricians: 31

Insulation workers: 29

Carpenters: 25

Laborers (excluding construction): 24

Supervisors, precision production workers: 18

Boilermakers: 18

Managers, administrators: 17

Welders, cutters: 17

Janitors, cleaners: 15

Other/not reported: 338

The most frequently recorded industries on death certificates of deceased from asbestosis were:

Construction: 149

Ship and boat building/repairing: 50

Industrial/miscellaneous chemicals: 23

Miscellaneous nonmetallic mineral stone products: 23

Railroads: 17

General government: 17

Yarn, thread, and fabric mills: 11

Other rubber products, plastic footwear, belting: 9

Unspecified manufacturing industries: 9

Trucking service: 9

Other/not reported: 261

Among those at risk are persons engaged in milling the ore, the manufacture of asbestos products, lagging, asbestos spraying, building, demolition, and laundering of asbestos worker’s overalls.

Sex Distribution

In 1992, there were 959 deaths from asbestosis in the US.

Male: 923 (96.2%)

Female: 36 (3.8%)

Age Distribution

In 1992, there were 959 deaths from asbestosis.

15-34: 0 (0%)

35-44: 3 (0.3%)

45-54: 13 (1.4%)

55-64: 124 (12.9%)

65-74: 371 (38.6%)

75-84: 355 (37%)

85+: 93 (9.7%)

Etiologic Agent

Asbestosis, similar to the other pneumoconioses, depends on the interaction of inhaled fibers with lung macrophages and other parenchymal cells. The initial injury occurs at bifurcations of small airways and ducts, where the stiff fibers land and penetrate. Macrophages both alveolar and interstitial attempt to ingest and clear the fibers and are activated to release chemotactic factors and fibrogenic mediators that amplify the response. Chronic deposition of fibers and persistent release of mediators eventually leads to generalized interstitial pulmonary inflammation and interstitial fibrosis. It is not completely understood why silicosis is a nodular fibrosing disease and asbestosis a diffuse interstitial process. The more diffuse distribution may be related to the ability of asbestos to reach alveoli more consistently or its ability to penetrate epithelial cells, or to both.

Pathogenesis

Once inhaled, the asbestos fibers deposit in the respiratory bronchioles and alveolar ducts. Fibrosis is initiated in the peribronchiolar area of the lung. As the disease progresses, the fibrotic process extends into adjacent alveoli. There is an approximately 15 year lag between the time of exposure and symptoms – often being closer to 20 years.

Complications

|

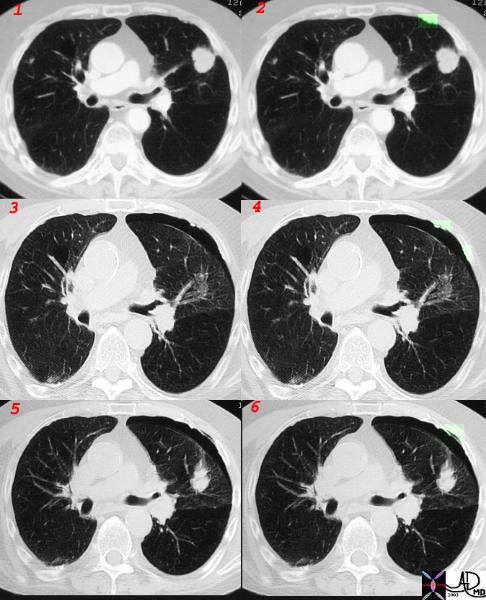

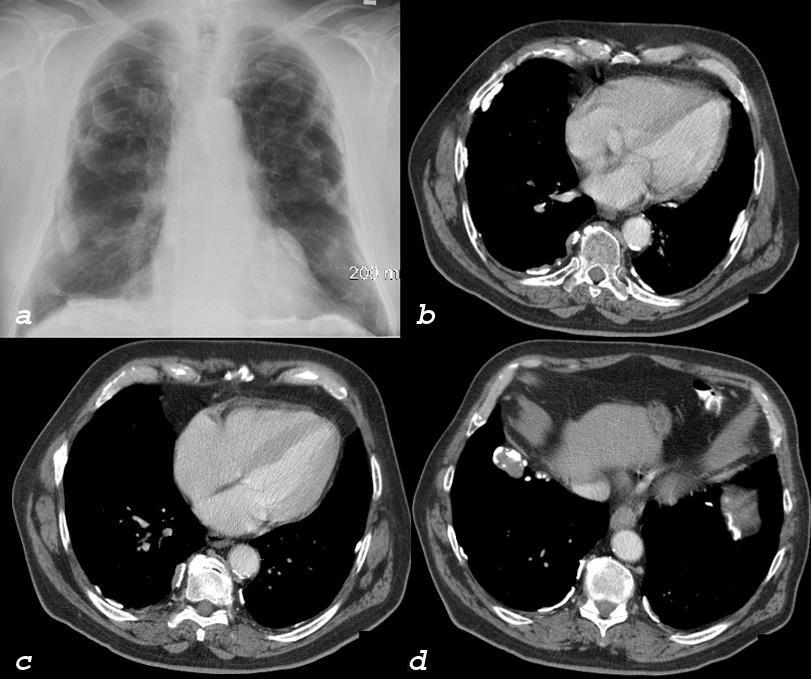

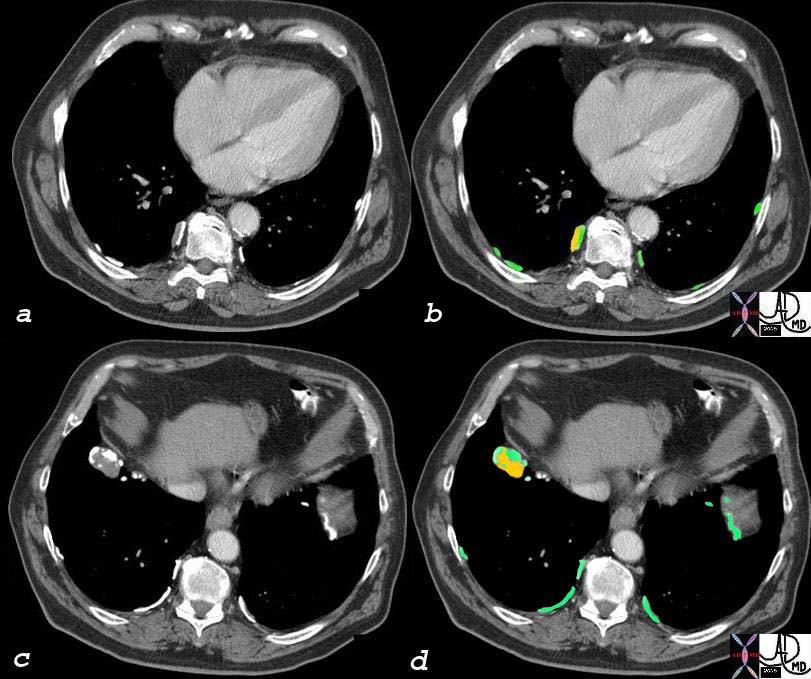

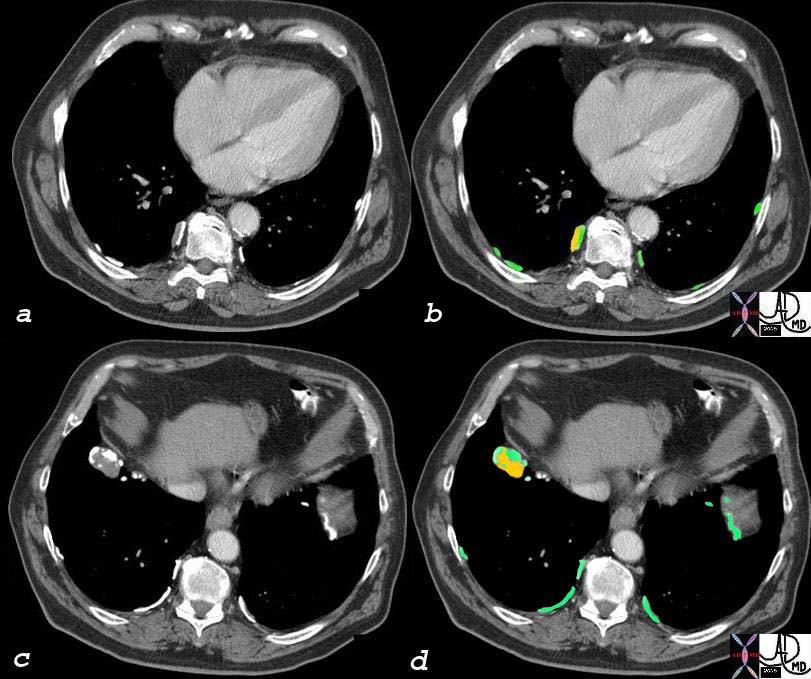

This combination image is a CT through a mass in the LUL showing focal pleural calcification overlayed in green (2) in this patient with asbestos related disease. A pneumothorax followed the biopsy revealing that the pleural plaques are positioned on the parietal pleura.(3,4) A small amount of air introduced from the xylocaine injection outlines the parietal pleura.(5,6) Courtesy Jorge Medina MD. 32017c.jpg

|

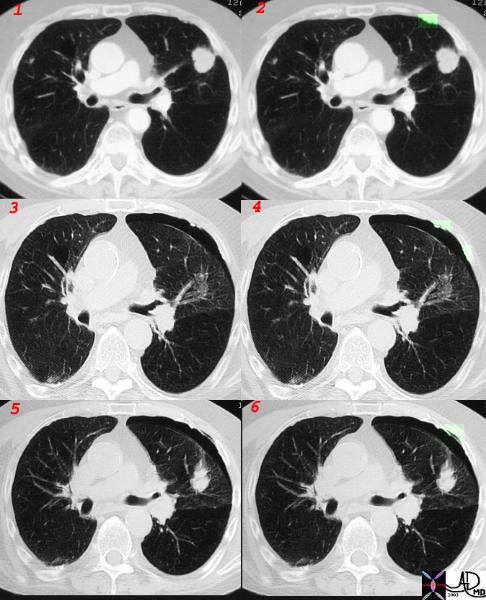

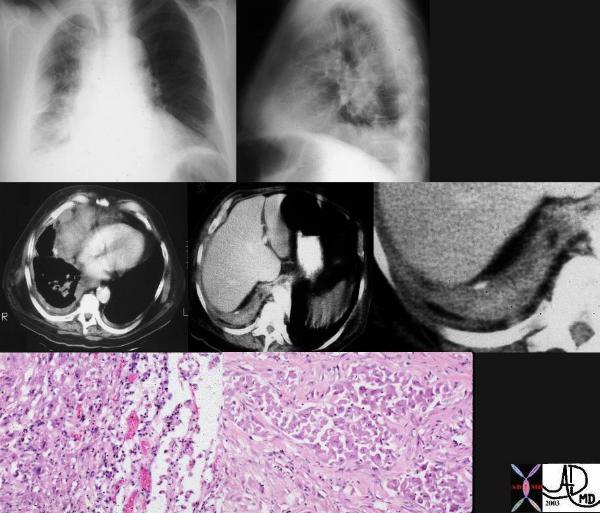

This combination of images are from a patient with mesothelioma associated with asbestos related disease. Note the pleural plaques in images 3,4,5, the contracted hemithorax (1), the pleural origin of the density (2) characterised by blunted costophrenic angle, and the rind of soft tissue around the heart (3) and in the posterior costophrenic spavce. (3,4). The pathology shows a combination of malignant proliferation of stromal and glandular elements (7) abutting relatively normal lung (6) Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD. 32215c code lung pleura mesothelioma mass malignant heart pericardium mesothelioma cardiac imaging radiology CXR plain film CT histopathology CTscan

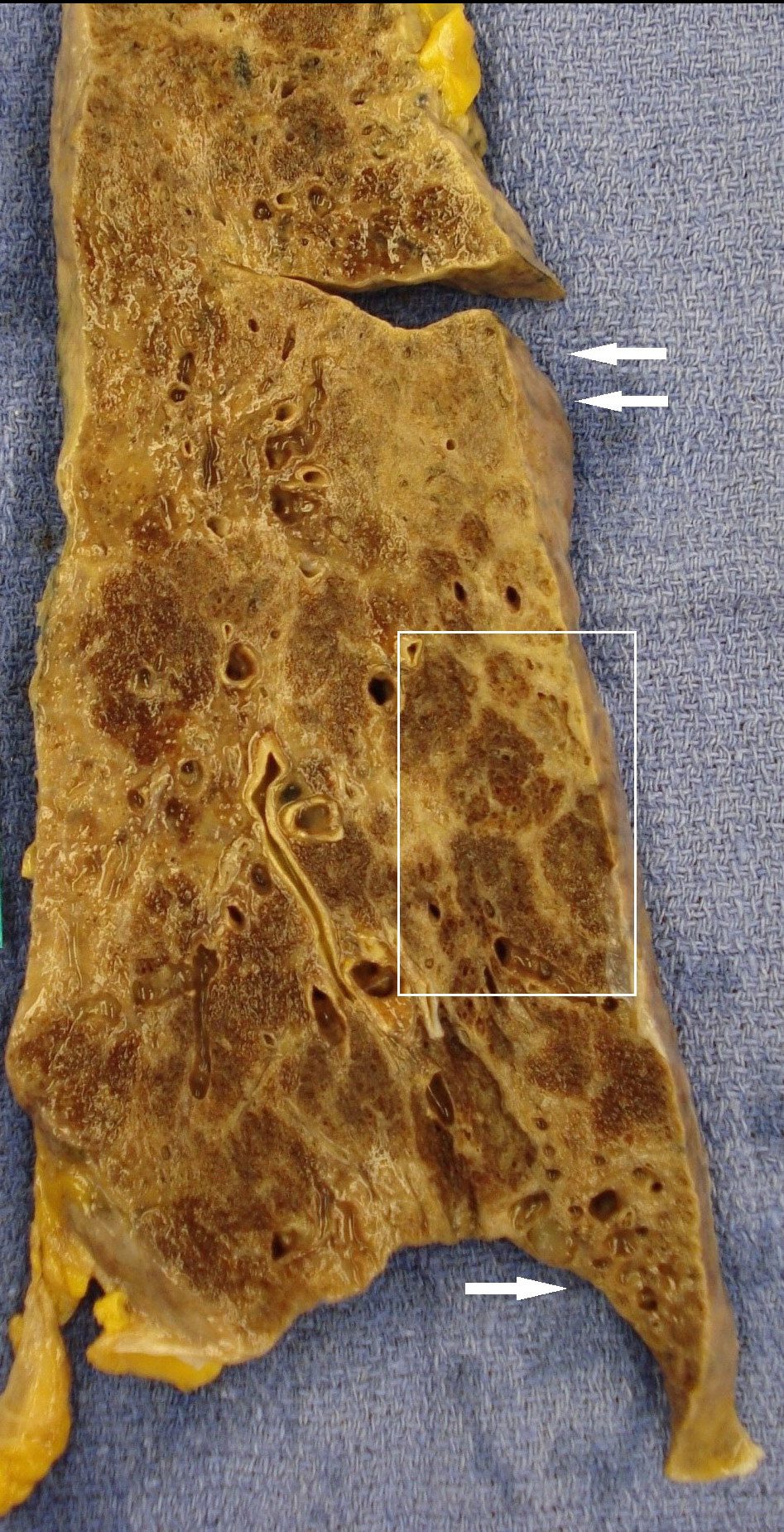

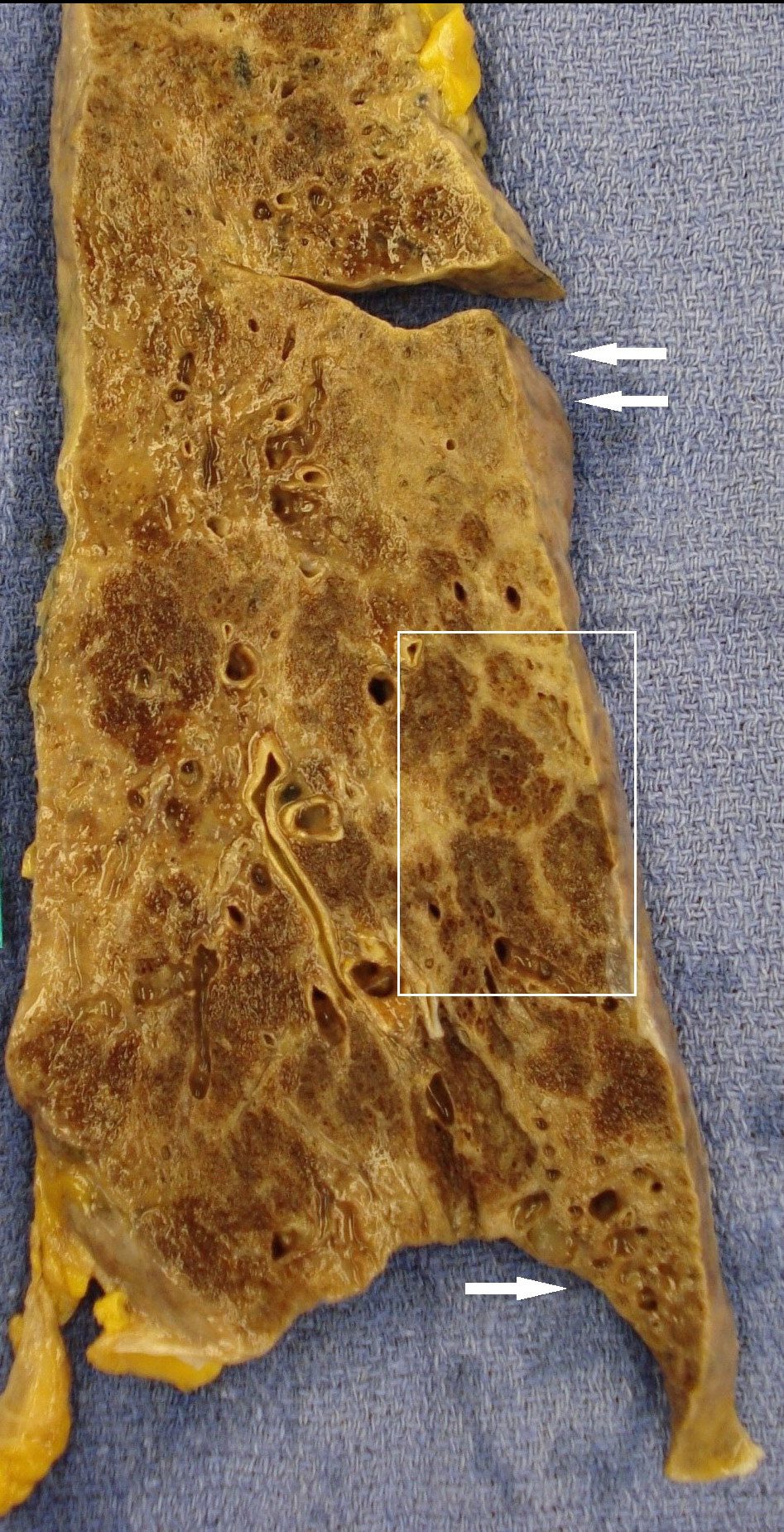

Gross pathology

PLEURAL DISEASE

Pleural plaques are abnormal collections of collagen that are attached to the parietal pleura, most commonly involving the posterolateral aspect of the thorax. 85% of the parietal pleural plaques are calcified. The calcification is recognized in only 15% of cases radiographically.

PARENCHYMAL DISEASE

The degree of fibrosis is related to both the duration and the magnitude of exposure.

This is a post mortem specimen shows a yellowish white pleural plaque in this patient with asbestos related disease. The plaque is on theparietal pleura. Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD. a87-156 32222 |

Imaging

PLEURAL DISEASE

The finding of bilateral calcified plaques on chest x-ray is a relatively specific marker for asbestos exposure.

Histologically 85% of the parietal pleural plaques are calcified; however, this calcification is recognized in only 15% of cases radiographically

pleura diaphragm calcification fibrous plaque asbestos related disease

CTscan CXR

Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD

75892c04

pleura

diaphragm

calcification

fibrous plaque

asbestos related disease

CTscan

Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD

75892c03

This collection of images show posteromedial bilateral focal regions of pleural thickening felt to represent non calcified pleural plaques, of asbestos related disease. Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD.

32401c

PARENCHYMAL DISEASE:

The chest x-ray is the most diagnostic examination The classical findings include irregular and linear opacities of the lower lobes. Middle lobe and lingula are also commonly involved giving rise to the “shaggy” heart border.

This is a frontal chest X-ray of a 66year old man who swept asbestos fibers off the floor for many years. The image characterizes the “shaggy heart border” due to the interstitial process in the middle lobe and lingula.

Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD 2019

32615.8

Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD 32617.8

Asbetosis Radiopedia