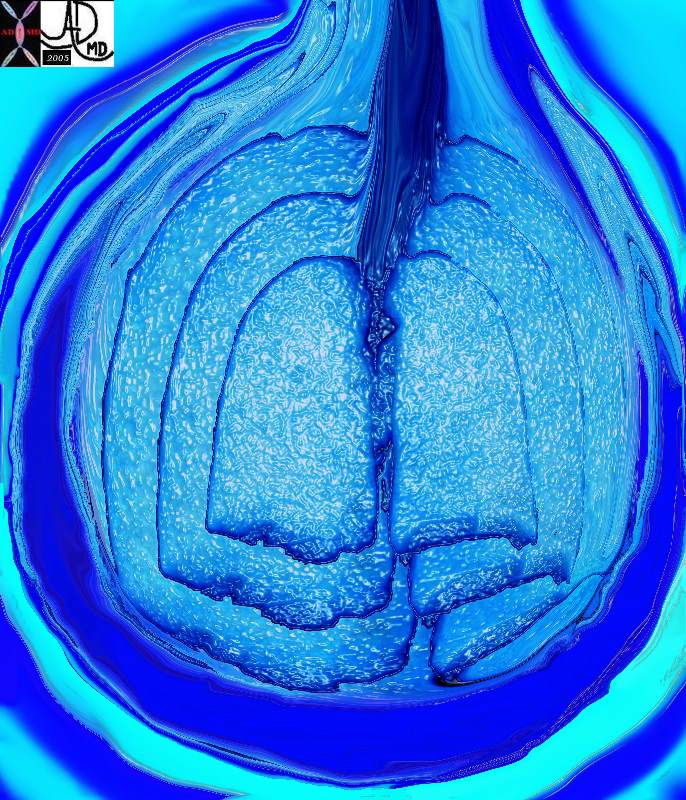

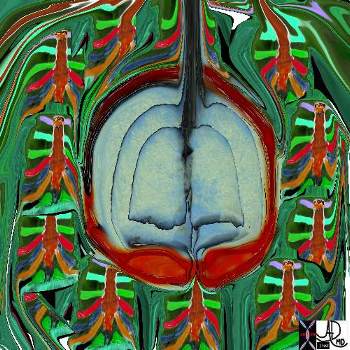

The chest quietly expands and contracts under basal conditions in order to serve the alveoli. At first glance it seems like a simple bellows-like process, but as one delves into the layers of detail, the complexity of the structural design unfolds as a combination of physical and chemical forces.

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net 42530b05b09b28

Courtesy of: Ashley Davidoff, M.D. TheCommonVein.net

42529b06aa04

The five major layers that keep the air moving include the outer bony cage, the muscular layer represented in maroon, the pleural complex (orange yellow orange) the lung (blue) and surfactant within the alveolus. (pink)

42530b05b09b01a08

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net

Courtesy of: Ashley Davidoff, M.D. TheCommonVein.net

42530b08

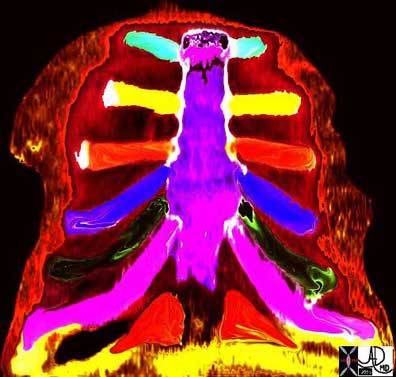

The chest is surrounded by a ring of muscle (maroon) made up of a various groups which work in concert. The diaphragm is the workhorse of the respiratory muscles and is shown as a thick maroon band inferiorly. Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net 42530b05b09b14

Ashley Davidoff, M.D.

42540b06

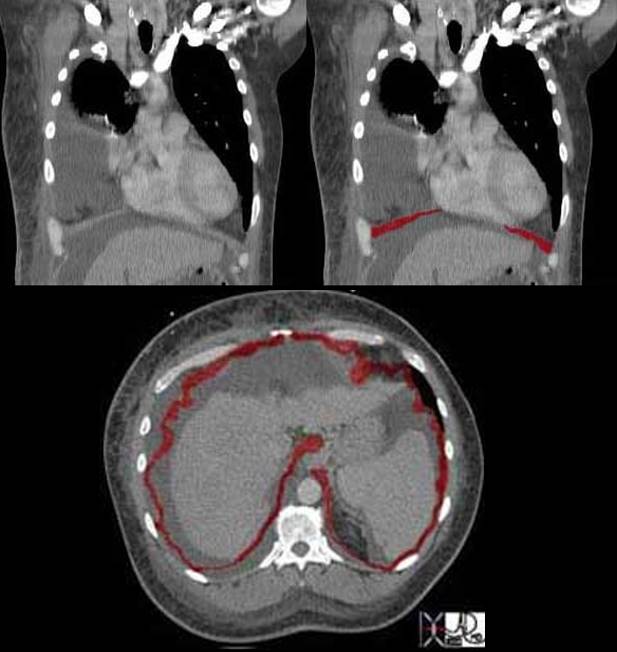

The diaphragm plays the most important role in breathing. Although it covers a large area it is relatively thin and therefore it usually cannot be fully appreciated on axial cuts. Can you see the diaphragm in this coronal image, and if so why is it so well seen? Additionally why do you think it does not continue all the way across the midline?

The reason we see the diaphragm so well is because there is fluid in both the chest cavity and abdominal cavity and the interface of fluid density on the contrasting soft tissue density of the diaphragm makes it more easily discernible. The central part of the diaphragm is called the central tendon of the diaphragm and it is in continuity with the pericardium. True to its name it is tendinous and therefore very thin and difficult to image.

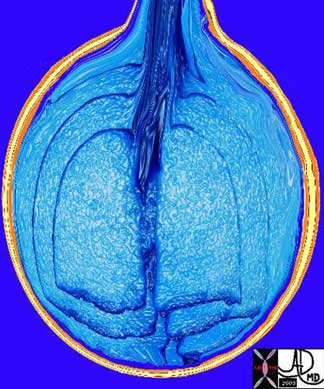

In this cross sectional image of the same patient the diaphragm is seen as an undulating thin muscle. Since it is dome shaped with its attachments inferiorly only parts in this particular cross section are seemingly attached to the ribs. The undulations are caused by tendinous attachments that extend from the ribs to the central tendon. The full diaphragm was not visualized in this patient and the digitally manipulated image has interpolated the data to provide a circumferential view.

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net 42557b04c