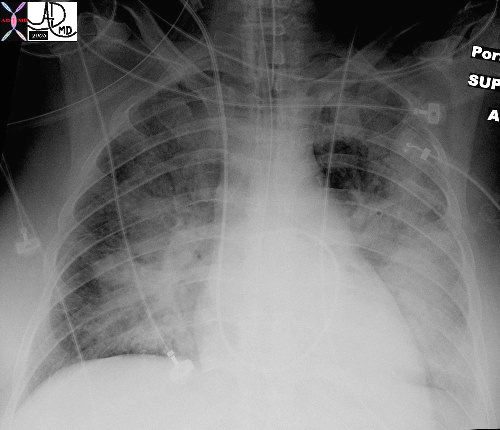

In this patient with acute congestive cardiac failure the consolidation that has hilar distribution has reminded radiologists of bat wings and butterfly wings and is caused by alveolar edema. As a result of the fluid in the alveoli, gas exchange across the respiratory membrane is reduced resulting in a decrease in oxygen saturation, and thus requiring intubation to improve the gas exchange process. Note the endotracheal tube as well as the central venous line that is used to assess the heart pressure and monitor the congestion.

Ashley Davidoff MDTheCommonVein.net 42073b01

In this patient with acute congestive cardiac failure the consolidation that has hilar distribution has reminded radiologists of bat wings and is caused by alveolar edema. As a result of the fluid in the alveoli, gas exchange across the respiratory membrane is reduced and required intubation to improve the gas exchange process. Note the endotracheal tube as well as the central venous line that is used to assess the heart pressure and monitor the congestion.

Ashley Davidoff MD

TheCommonVein.net 42073b01

Memory Image Neelou Etesami MS4 PhD

References

- Clinical and Radiologic Features of Pulmonary Edema. Gluecker T, Capasso P, Schnyder P, et al. Radiographics : A Review Publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 1999 Nov-Dec;19(6):1507-31; discussion 1532-3. doi:10.1148/radiographics.19.6.g99no211507.

- CT Signs and Patterns of Lung Disease. Collins J. Radiologic Clinics of North America. 2001;39(6):1115-35. doi:10.1016/s0033-8389(05)70334-1.

- Radiographic Features of Cardiogenic Pulmonary Oedema in Cats With Left-Sided Cardiac Disease: 71 Cases. Diana A, Perfetti S, Valente C, et al Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 2022;24(12):e568-e579.

- Chest CT Signs in Pulmonary Disease: A Pictorial Review. Raju S, Ghosh S, Mehta AC. 2017;151(6):1356-1374. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2016.12.033.

- Hydrostatic Pulmonary Edema: Evaluation With Thin-Section CT in Dogs. Scillia P, Delcroix M, Lejeune P, et al. 1999;211(1):161-8. doi:10.1148/radiology.211.1.r99ap07161.

- Ultrasound of Extravascular Lung Water: A New Standard for Pulmonary Congestion., Picano E, Pellikka PA. European Heart Journal. 2016;37(27):2097-104. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw1647.Diseases Involving the Lung Peribronchovascular Region: A CT Imaging Pathologic Classification. Le L, Narula N, Zhou F, et al 2024;166(4):802-820. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2024.05.033.

- Lung Morphology and Surfactant Function in Cardiogenic Pulmonary Edema: A Narrative Review. Nugent K, Dobbe L, Rahman R, Elmassry M, Paz P. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 2019;11(9):4031-4038. doi:10.21037/jtd.2019.09.02.

- .Radiographic Appearance of Presumed Noncardiogenic Pulmonary Edema and Correlation With the Underlying Cause in Dogs and Cats. Bouyssou S, Specchi S, Desquilbet L, Pey P. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound : The Official Journal of the American College of Veterinary Radiology and the International Veterinary Radiology Association. 2017;58(3):259-265. doi:10.1111/vru.12468.

- CT Approach to Lung Injury. Marquis KM, Hammer MM, Steinbrecher K, et al. Radiographics : A Review Publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2023;43(7):e220176. doi:10.1148/rg.220176.

- Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (An Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2022;205(9):e18-e47. doi:10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST.

- Diagnosis and Evaluation of Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Fernández Pérez ER, Travis WD, Lynch DA, et al. 2021;160(2):e97-e156. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.03.066.