Hampton’s Hump: Radiology Perspective

Definition

- Hampton’s hump is a wedge-shaped, pleural-based opacity on chest imaging caused by pulmonary infarction, often secondary to pulmonary embolism (PE).

- Represents necrosis and hemorrhage in lung parenchyma due to ischemia.

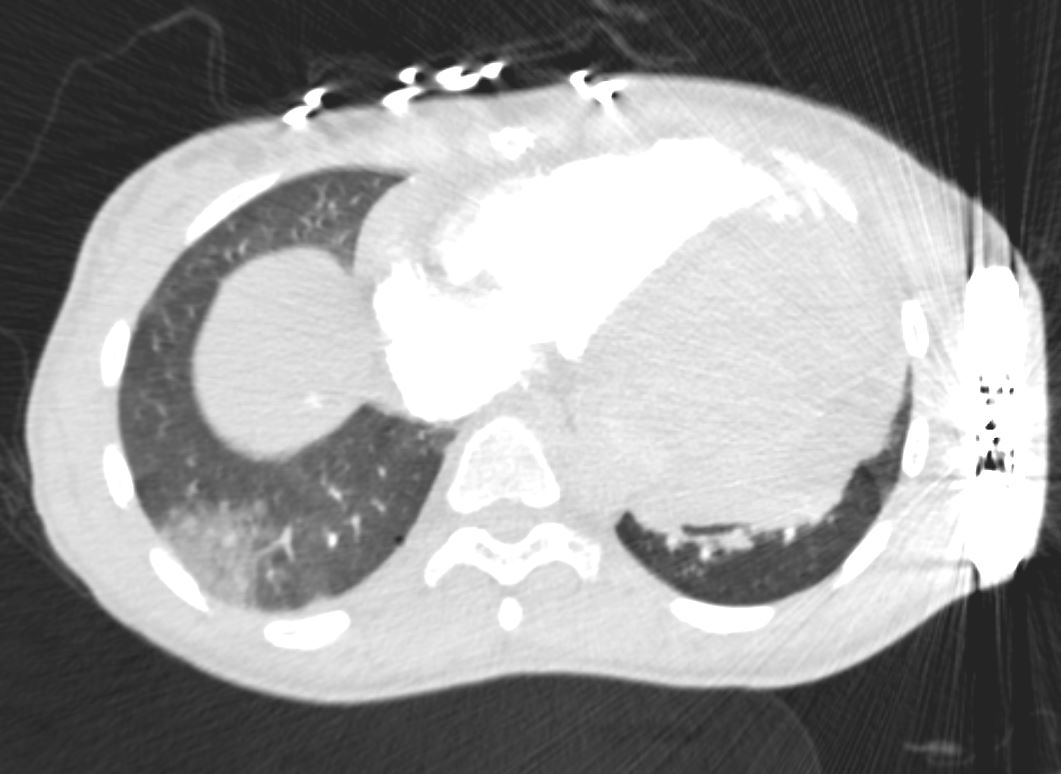

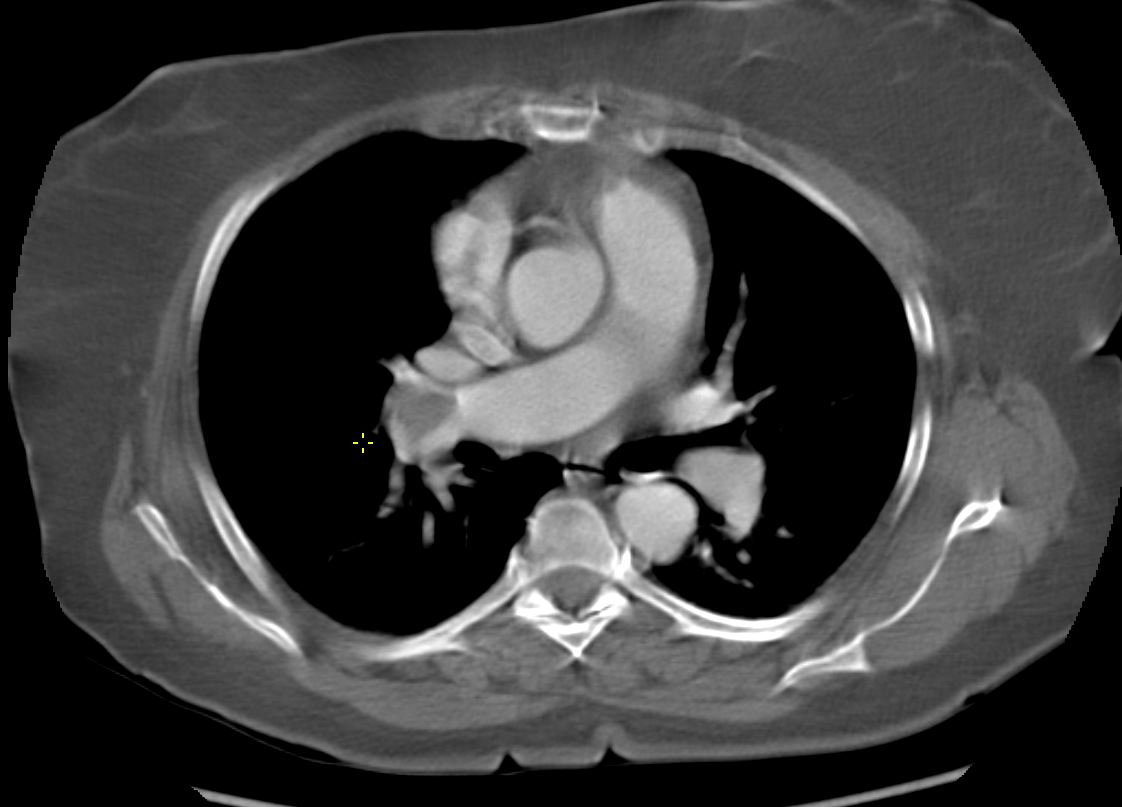

35-year-old female with an 8-year history of post- partum cardiomyopathy presents with a history of chest pain. CT of the chest with contrast in an axial projection, at the level of the heart, shows a subsegmental wedge shaped ground glass infarct in the posterior or lateral region of the right lower lobe likely reflecting a hemorrhagic infarct. An external defibrillator is present.

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net 258Lu 136169a

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonvein.net 24f PE Hampton’s hump 001

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonvein.net 24f PE Hampton’s hump 002

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonvein.net 24f PE Hampton’s hump 003

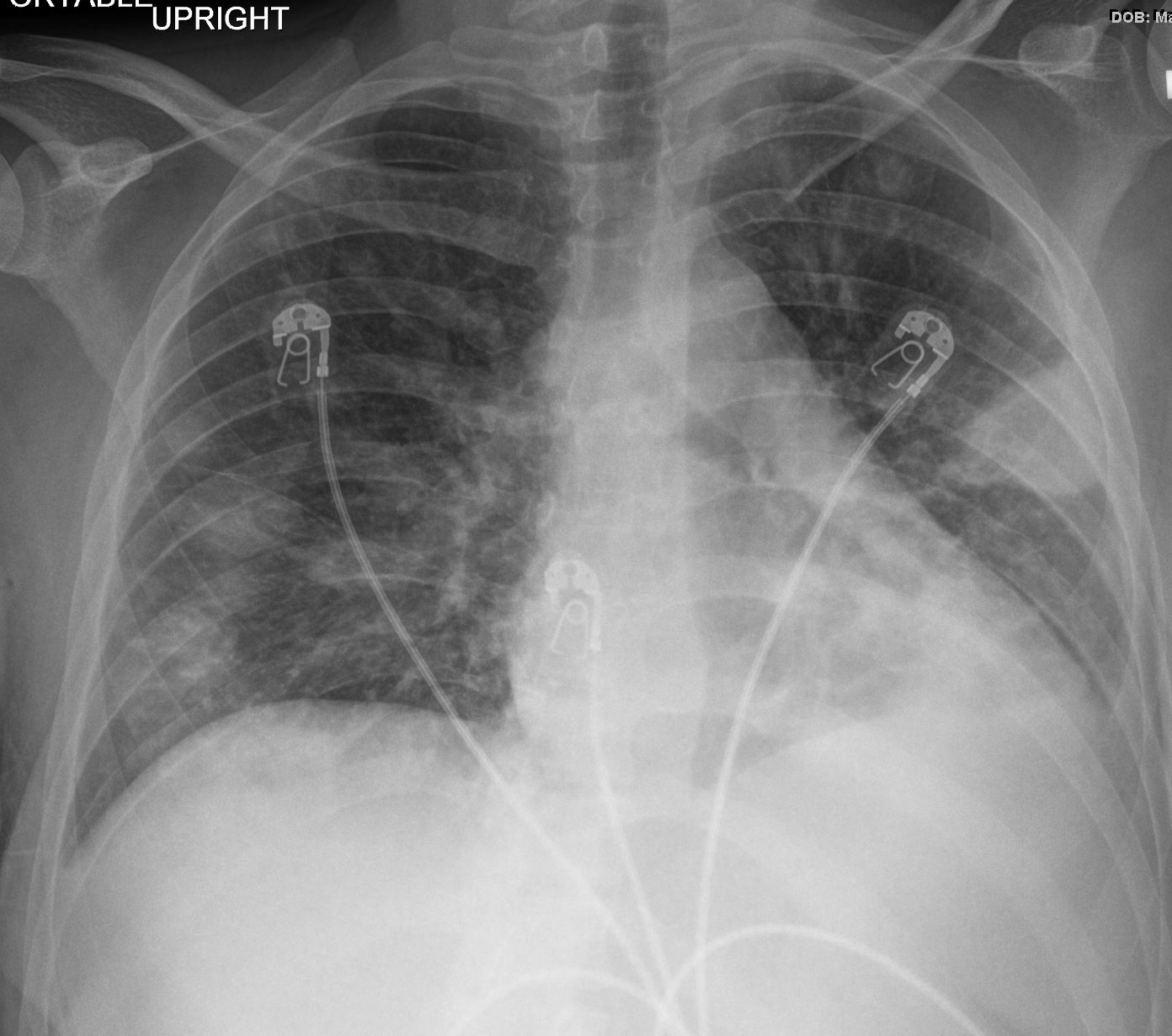

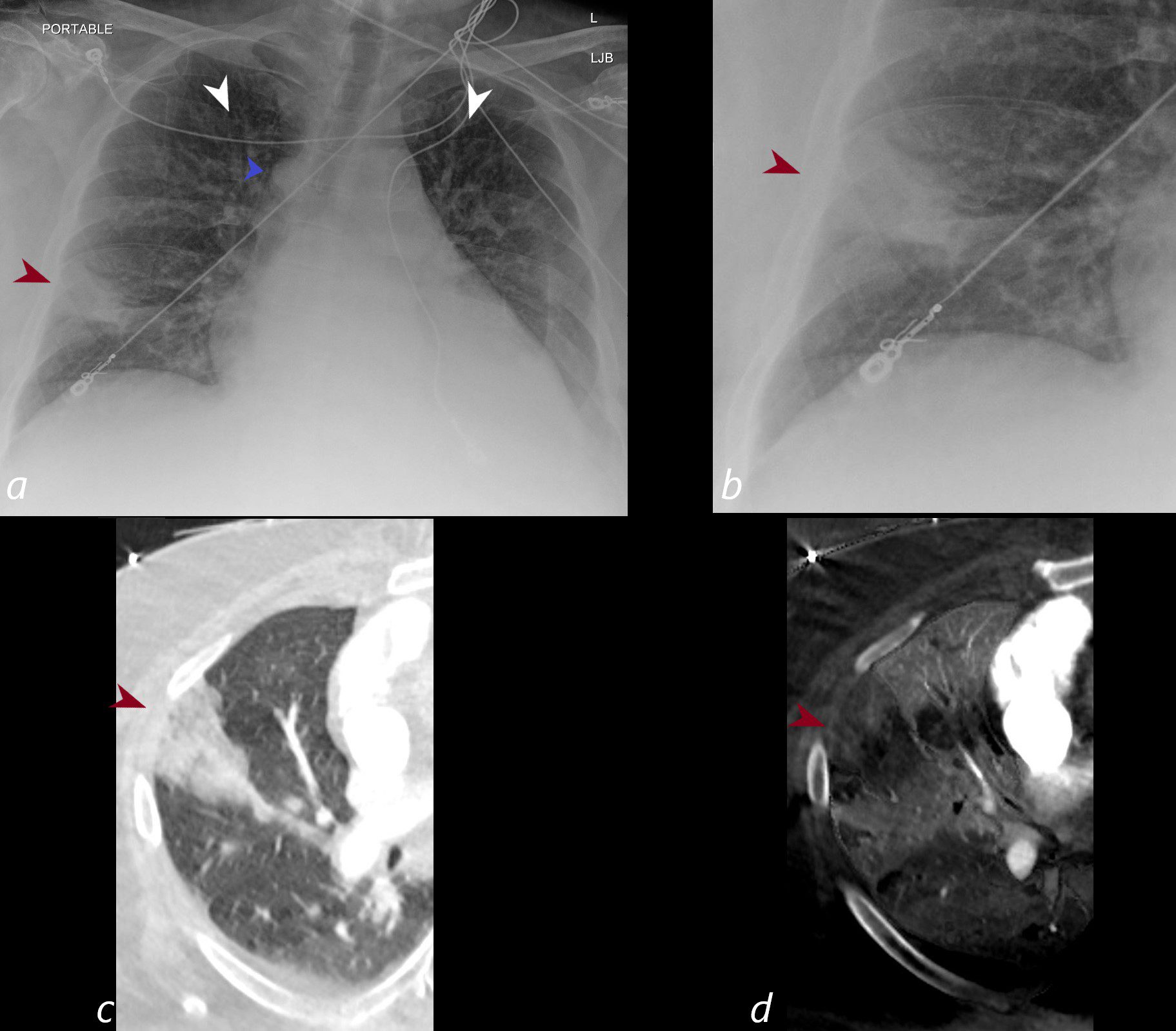

CXR shows a wedge shaped ground glass opacity in the middle lobe of the lung secondary to a pulmonary embolus (PE) characteristic of a Hampton’s hump (maroon arrowheads a,b) The infarction is confirmed on the CT with contrast (maroon arrowhead c) as well as the region of a perfusion defect (d- maroon arrowhead) In addition there is evidence of CHF on the CXR with cephalization of the vessels (white arrowheads c) cardiomegaly with left atrial enlargement, and enlargement of the azygous vein (blue arrowhead a)

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net)

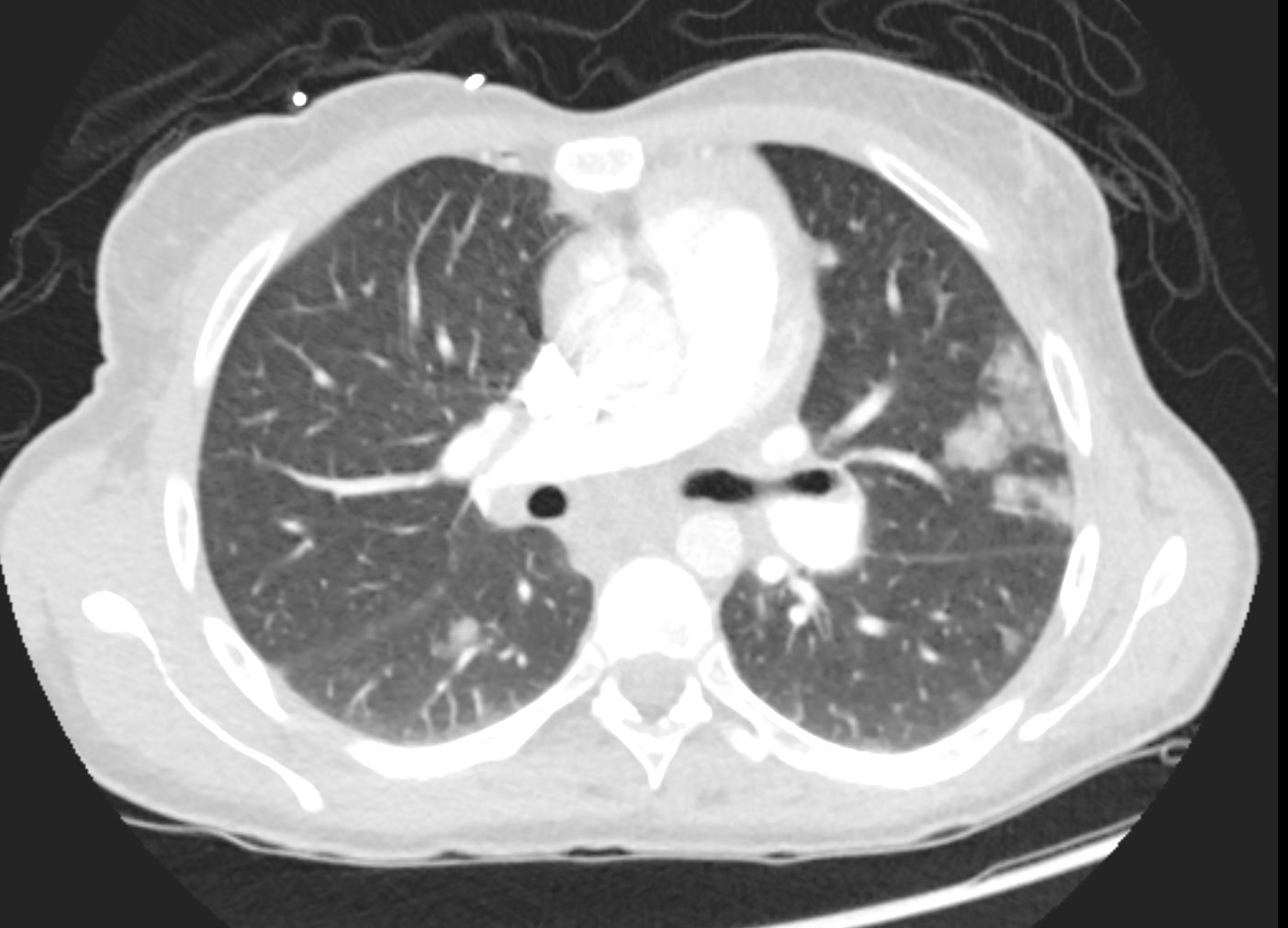

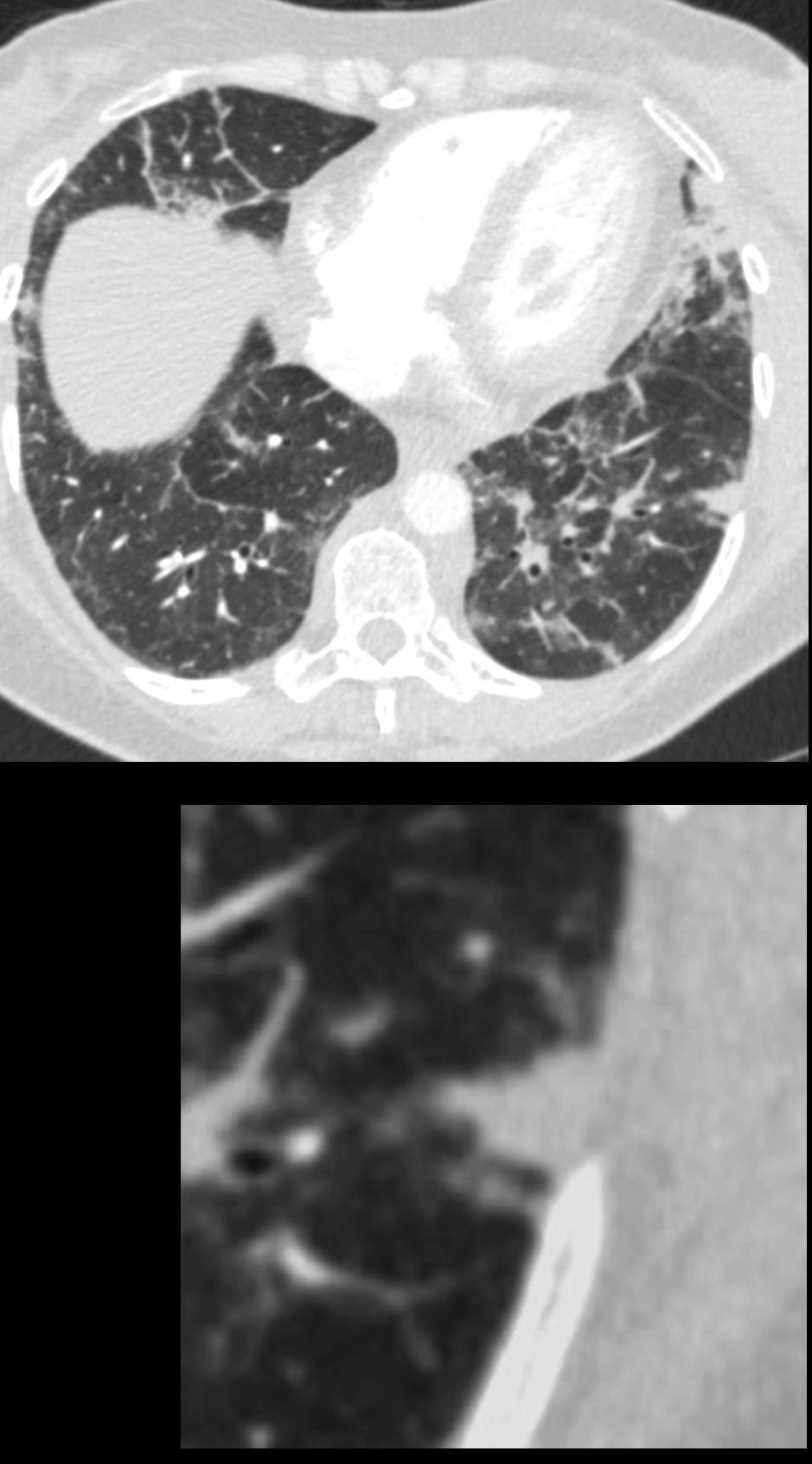

56 -year-old female with a history of amyloidosis presenting with tachycardia and dyspnea. Lung windows from the CTPA a subsegmental wedge shaped defect (Hampton’s hump) in the lateral segment of the left lower lobe. The lung parenchyma is intact in the left lower lobe in the region of lack of lobar perfusion on the dual energy iodine maps, indicating that despite the lack of perfusion there is no necrosis

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net 135742

56 -year-old female with a history of amyloidosis presenting with tachycardia and dyspnea. CTPA shows no contrast enhancement of the pulmonary arteries subtending the left lower lobe compared to the right and a subsegmental wedge shaped defect (Hampton’s hump) in the lateral segment of the left lower lobe

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net 135739c

CTPA 15 years ago shows a large thrombotic embolus in the right main pulmonary artery extending into the middle lobe artery

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net 136172

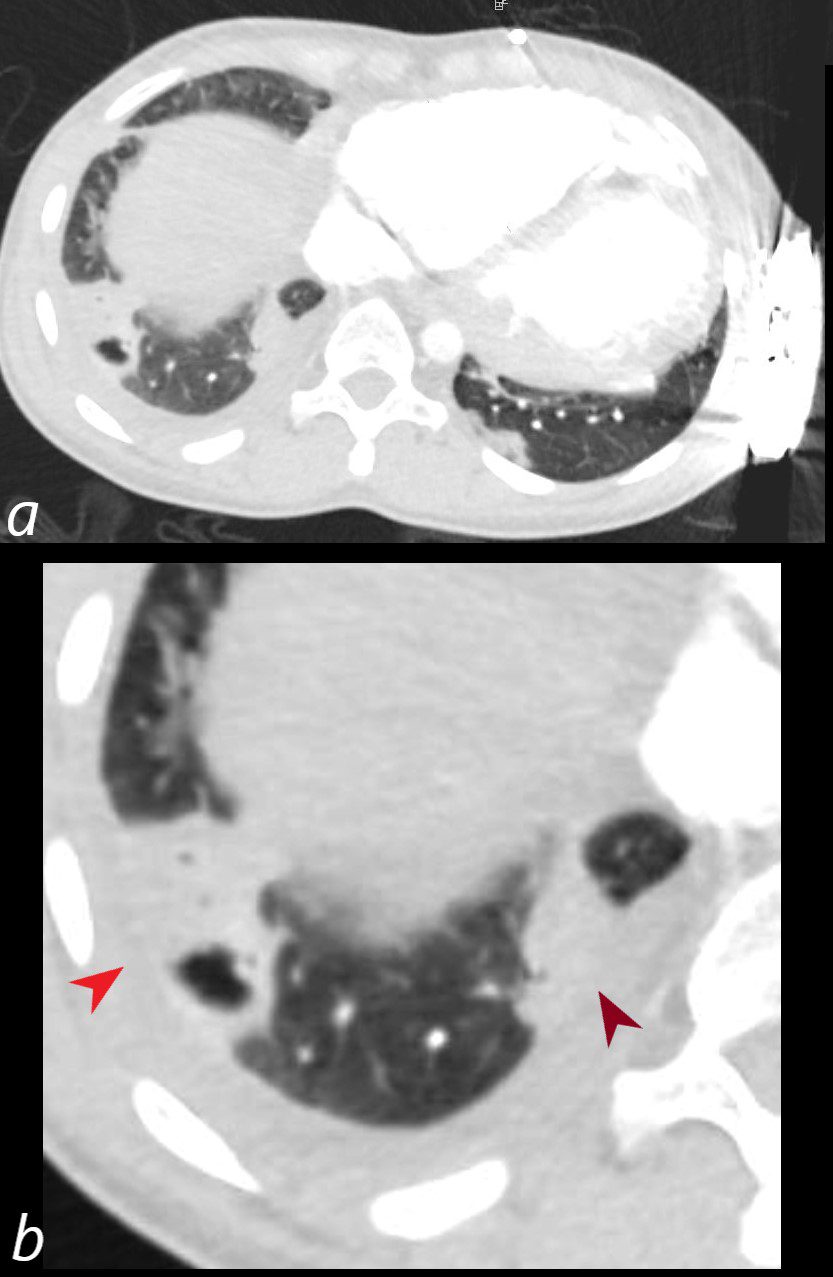

35-year-old female with an 8-year history of post- partum cardiomyopathy presents with a history of ongoing chest pain and fever 1 week following new cavitation of a pulmonary infarction. CT of the chest with contrast in an axial projection, at the level of the heart shows an enlarged right ventricle, evolution of the posterolateral infarction into an abscess with a bubble of air, enhancing wall, a small right pleural effusion with suggestion of pleural enhancement in the left lower lobe.

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net 253Lu 136174

35-year-old female with an 8-year history of post- partum cardiomyopathy presents with a history of ongoing chest pain 10 days following acute pulmonary infarction. CT of the chest with contrast in an axial projection, at the level of the heart shows an enlarged right ventricle, cavitation of the previously identified posterolateral infarction (b, red arrowhead), a persistent wedge shaped subsegmental infarct medially (b maroon arrowhead), a small right pleural effusion, and subsegmental atelectasis in the left lower lobe.

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net 258Lu 136173cL

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

Causes

- Pulmonary Embolism (PE): Most common underlying cause.

- Septic Emboli:

- Emboli arising from infected thrombi or cardiac vegetations (e.g., infective endocarditis).

- Common in intravenous drug users or patients with infected central venous catheters.

- Non-thrombotic Emboli:

- Fat embolism (e.g., trauma or orthopedic surgery).

- Amniotic fluid embolism.

- Tumor embolism.

- Risk factors for PE:

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

- Immobility, surgery, or trauma.

- Hypercoagulable states (e.g., malignancy, pregnancy, inherited clotting disorders).

Results

- Pulmonary infarction: Ischemic necrosis of lung tissue.

- Adjacent pleural inflammation causing pleuritic chest pain.

- May resolve or progress to scarring.

Diagnosis

- Clinical Presentation:

- Sudden onset of dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and hemoptysis.

- Signs of DVT or systemic infection (e.g., fever, sepsis) in cases of septic emboli.

- Imaging:

- Chest X-ray (CXR):

- Peripheral, pleural-based, wedge-shaped opacity.

- Base of the wedge contacts the pleura, apex points towards the hilum.

- May be subtle or absent in early PE.

- Chest CT Pulmonary Angiography (CTPA):

- Confirms PE by showing filling defects in pulmonary arteries.

- Better characterization of the infarcted region.

- Septic emboli: May show cavitation or nodular opacities associated with the wedge.

- Pleural effusion may accompany the finding.

- Nuclear Medicine V/Q Scan:

- Mismatched perfusion defect in cases of PE.

- Chest X-ray (CXR):

- Laboratory Tests:

- Elevated D-dimer (non-specific).

- Arterial blood gas: Hypoxemia, respiratory alkalosis.

- Blood cultures and inflammatory markers in suspected septic emboli.

- Coagulation studies to identify hypercoagulable states.

Treatment

- Anticoagulation:

- Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), or warfarin.

- Long-term therapy duration based on risk factors.

- Thrombolysis:

- For massive PE with hemodynamic instability.

- Antibiotics (for septic emboli):

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics tailored to identified pathogens.

- Supportive Care:

- Oxygen therapy for hypoxia.

- Pain management for pleuritic pain.

- Prevention of Recurrence:

- Inferior vena cava (IVC) filter in patients contraindicated for anticoagulation.

- Treat underlying risk factors (e.g., malignancy, immobility, or infection).

Pearls

- Hampton’s hump is a hallmark of pulmonary infarction but is seen in only a minority of PE cases.

- May mimic other conditions like pneumonia; clinical correlation is essential.

- Septic emboli may also result in cavitation, requiring differentiation from other causes of nodular or wedge-shaped opacities.

- Absence of Hampton’s hump on imaging does not rule out PE.

- CTPA is the gold standard for diagnosing PE and its associated findings.

Historical Perspective

The first documentation of the finding was made by Aubrey Otis Hampton, who was a practicing radiologist in the mid 1920s. He and his co-author Castleman first reported evidence of incomplete pulmonary infarction in the setting of PE in the 1940s.