-

-

- Etymology

“Nodule” originates from the Latin word nodulus, meaning a small knot. - AKA and abbreviation

Pulmonary nodule, solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN), multiple pulmonary nodules (MPNs), ground-glass nodule (GGN). - What is it?

A lung nodule is a rounded or irregular focal opacity in the lung parenchyma, measuring up to 3 cm in diameter. Nodules are categorized based on their imaging characteristics and clinical context. - Characterized by

- Size:

- Micronodules: <2 mm in diameter.

- Miliary nodules: Tiny, uniformly distributed nodules, typically <2 mm in size, comparable to the size of a millet seed.

- Nodules: 2 mm to 30 mm (3 cm).

- Masses: >3 cm in diameter.

- Opacity: Can be solid, ground-glass, or part-solid. Each of these types will be addressed separately due to differing implications and management strategies. Includes calcifications (central, eccentric, psammomatous), cavitation, and fat-containing nodules.

- Margins: Smooth, lobulated, spiculated, or irregular.

- Distribution: Solitary or multiple; localized or diffuse, random, bronchocentric, interlobular septum, or intralobular locations.

- Size:

- Caused by

- Most Common Cause(s): Benign etiologies such as granulomas (e.g., from tuberculosis or histoplasmosis) and hamartomas. Malignant causes include primary lung cancer or metastases.

- Other Causes Include:

- Infection: Fungal infections, bacterial abscesses.

- Inflammation/Immune: Sarcoidosis, rheumatoid nodules.

- Neoplasm: Adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, metastatic disease.

- Congenital: Bronchopulmonary sequestration, arteriovenous malformations.

- Resulting in:

- Potential for malignancy if persistent or showing growth.

- Misinterpretation leading to unnecessary investigations or interventions.

- Structural changes:

- Localized changes in lung parenchyma with varying degrees of surrounding fibrosis or inflammation.

- Pathophysiology:

- Benign nodules often represent focal granulomatous inflammation or congenital abnormalities.

- Malignant nodules develop due to uncontrolled cellular proliferation.

- Pathology:

- Benign: Granulomas, hamartomas, or inflammatory nodules.

- Malignant: Primary lung cancers (e.g., adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma) or metastatic lesions.

- Diagnosis:

- Clinical history: Risk factors such as smoking, exposure to carcinogens, or travel to endemic areas.

- Imaging: Chest X-ray, CT (standard and HRCT), and PET-CT.

- Biopsy: Indicated for nodules with high suspicion of malignancy.

- Clinical:

- Often asymptomatic and incidentally detected.

- Symptomatic nodules may cause cough, hemoptysis, or systemic symptoms if associated with malignancy or infection.

- Radiology Detail:

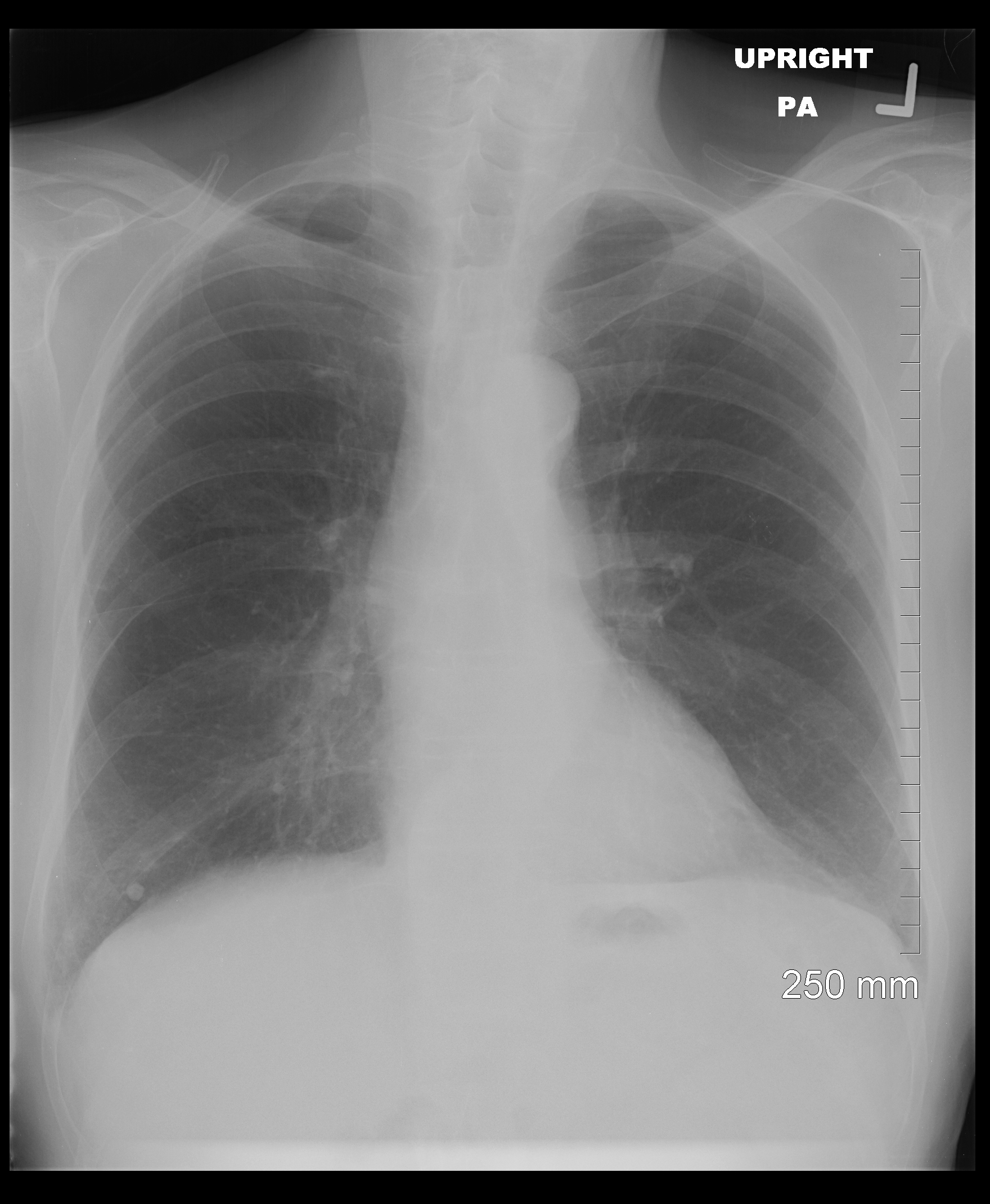

- CXR

- Findings: Solitary or multiple opacities.

- Associated Findings: Hilar lymphadenopathy, pleural effusion.

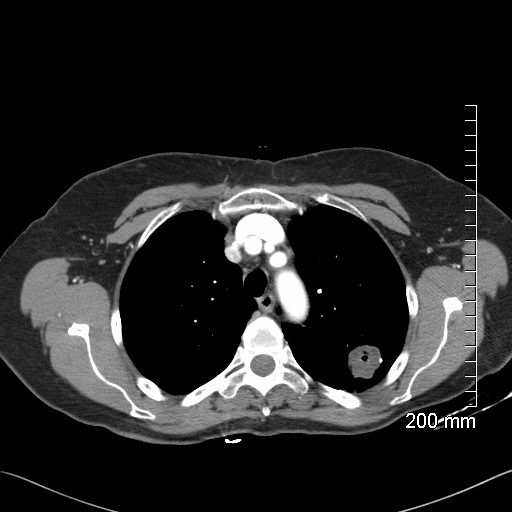

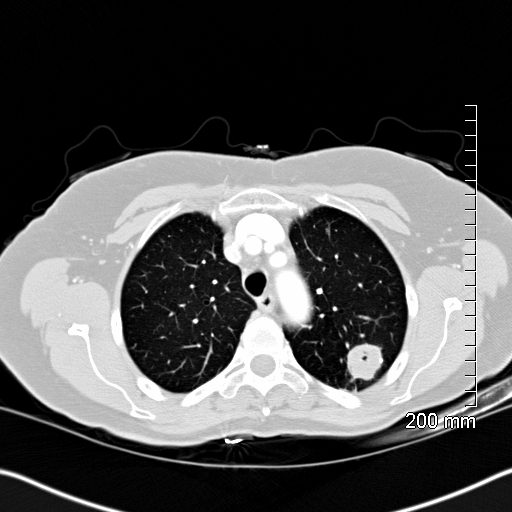

- CT

- Parts: Solitary or multiple.

- Size:

- Micronodules: <2 mm in diameter.

- Miliary nodules: Tiny, uniformly distributed nodules, typically <2 mm in size, comparable to the size of a millet seed.

- Nodules: 2 mm to 30 mm (3 cm).

- Masses: >3 cm in diameter.

- Shape: Round, oval irregular, spiculated or lobulated.

- Position:

- Centrilobular nodules: Associated with the small airways; common in conditions such as hypersensitivity pneumonitis, endobronchial spread of infection, or smoking-related diseases.

- Nodules in the interlobular septum: Often imply lymphatic or vascular spread and are seen in sarcoidosis, lymphangitic carcinomatosis, or pulmonary edema.

- Nodules associated with fissures: Suggest benign lymphoid tissue, sarcoidosis, or less commonly, pleural-based processes such as mesothelioma, metastatic disease, or subpleural lymphatic spread.

- Nodules near the pleura: Can indicate inflammatory conditions (e.g., rheumatoid nodules) or malignancies with pleural involvement.

- Random distribution of nodules: Seen in hematogenous spread, such as in metastatic disease or miliary tuberculosis, indicating systemic involvement.

- Miliary nodules appear as tiny, uniformly distributed nodules throughout the lung fields.

- Character: Solid, ground-glass, or part-solid. Includes calcifications (solid: central, eccentric, irregular, psammomatous), fat, necrotizing, and mixed components, as well as cavitation.

- Time: Stable, transient, or progressive. Malignant nodules typically double in size within 20-400 days. For example, a 5 mm malignant nodule may grow to 7 mm within 60-90 days if aggressively doubling. Benign nodules, such as granulomas, rarely grow significantly over time, while hamartomas may exhibit very slow growth, often negligible over years.

- Growth Rates:

- Malignant nodules typically double in size within 20-400 days, while benign nodules often remain stable. For example:

-

- A 3 mm malignant nodule may grow to approximately 4 mm to 5 mm within 60-90 days.

- A 5 mm malignant nodule may grow to approximately 6-7 mm within 60-90 days.

- A 7 mm malignant nodule may grow to approximately 9-10 mm within 60-90 days.

- A 10 mm malignant nodule may grow to approximately 12-14 mm within 60-90 days.

-

- GGNs grow more slowly than solid nodules, often necessitating prolonged follow-up to detect late malignant transformation.

- Malignant nodules typically double in size within 20-400 days, while benign nodules often remain stable. For example:

- Associated Findings: Calcifications, cavitation, spiculation, pleural retraction.

- Other relevant Imaging Modalities

- PET-CT: Recommended for nodules ≥7 mm with solid components or part-solid nodules with concerning features. PET-CT is less reliable for pure ground-glass nodules due to their paucicellular nature.

- MRI: Rarely used but can aid in characterizing soft tissue.

- CXR

- Pulmonary function tests (PFTs):

Usually normal unless associated with extensive disease or underlying lung pathology. - Recommendations

- Fleischner Guidelines:

- Solid nodules: Stable nodules ≤6 mm generally do not require follow-up unless risk factors are present, in which case the Fleischner guidelines recommend follow-up imaging at 12 months.

- GGNs >6 mm require follow-up at 6-12 months and, if stable, every 2 years for up to 5 years.

- Part-solid nodules: Nodules >6 mm with a solid component require close follow-up, including imaging at 3-6 months to confirm persistence and subsequent surveillance.

- Management:

- Biopsy or surgical resection for nodules with high suspicion of malignancy or significant growth.

- Serial imaging to monitor for stability or changes.

- Fleischner Guidelines:

- Key Points and Pearls

- The risk of malignancy increases with size, spiculation, and metabolic activity.

- Benign features include calcifications (central, eccentric, psammomatous), stability over time, and smooth margins.

- A structured approach to evaluation, including Fleischner guidelines, minimizes unnecessary procedures.

- Ground-glass nodules require longer follow-up compared to solid nodules due to their slower growth rate and potential for late malignant transformation.

- PET-CT is most effective for solid or part-solid nodules ≥7 mm and less reliable for pure GGNs.

- Etymology

- Centrilobular

-

Centrilobular Nodules

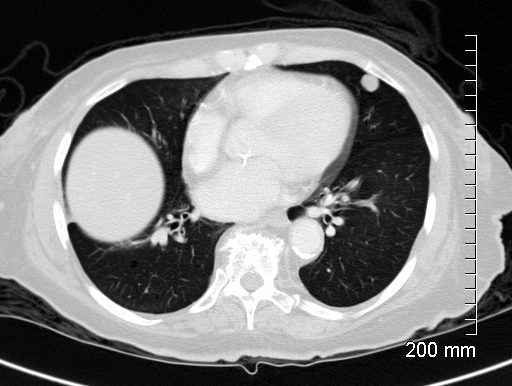

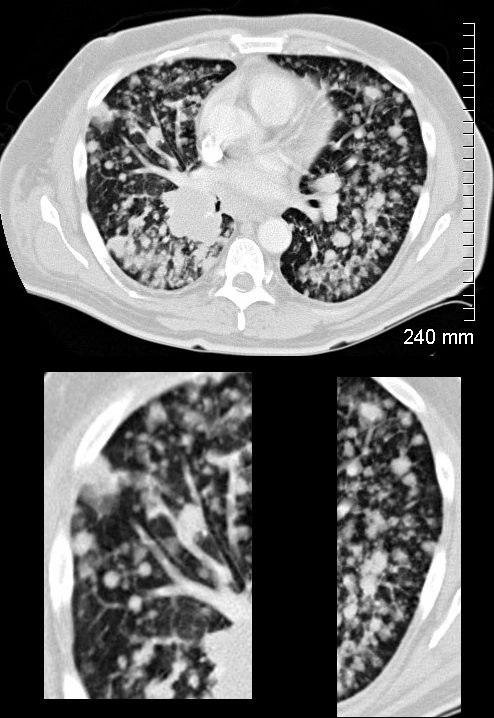

77F with long history of dyspnea and cough showing medium and small airway disease, centrii-lobular nodules, paraseptal nodules ground glass changes and mosaic attenuation Diagnosis includes Stage 3 sarcoidosis

Ashley Davidoff

TheCommonVein.net

-

-

Based on Character

- Solid

- Subsolid

- Ground Glass

- Calcified

Lung nodules, by definition are less than 3 centimeters in diameter and are quite common. Lung nodules can be categorized based on their appearance, size, and other characteristics. The most common types of lung nodules seen on CT scans include:

Solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN): This refers to a single lung nodule that appears as a well-defined round or oval lesion in the lung tissue.

Lung Nodule

- What is it:

- A lung nodule is a small, round or oval lesion within the lung parenchyma.

- It measures up to 3 cm in diameter; lesions larger than 3 cm are classified as masses.

- Etymology:

- Derived from the Latin word nodulus, meaning “small knot,” emphasizing its discrete and localized nature.

- AKA:

- Pulmonary nodule.

- Abbreviation:

- LN (Lung Nodule).

- How does it appear on each relevant imaging modality:

- Chest CT (preferred):

- Parts: Can be solid, subsolid (part-solid), or ground-glass (GGN).

- Size: Up to 3 cm in diameter; typically categorized into:

- Small nodules (<8 mm).

- Larger nodules (≥8 mm).

- Shape: Typically round or oval with smooth or irregular margins.

- concerning when it is spiculated

- Position: Can occur in any lung lobe; may be single or multiple.

- upper lung predominance

- Common Causes:

- Infection:

- Tuberculosis (TB): Upper lobes are frequently affected due to higher oxygen tension, which supports the growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

- Fungal infections (e.g., histoplasmosis, aspergillosis).

- Inflammation:

- Sarcoidosis: Typically shows nodules in a perilymphatic distribution, often involving the upper lobes.

- Neoplasm:

- Primary lung cancers (e.g., adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma): More common in upper lobes, especially in smokers.

- Pancoast tumors: Appear at the lung apex, a subset of upper lobe malignancies.

- Infection:

Lower Lobe Nodules

- Common Causes:

- Infection:

- Aspiration pneumonia: Often localized to the lower lobes due to gravity-dependent positioning.

- Pulmonary abscess.

- Inflammation:

- Rheumatoid nodules and interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) such as nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) commonly involve lower lobes.

- Neoplasm:

- Metastatic disease: Often found in the lower lobes due to the distribution of blood flow (hematogenous spread).

- Infection:

Peripheral vs. Central Distribution

- Peripheral nodules: Often associated with infections (e.g., fungal or septic emboli), metastatic disease, or inflammatory conditions like eosinophilic granuloma or organizing pneumonia.

- Central nodules: More likely to be due to malignancy (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma), endobronchial infections, or lymph node enlargement.

Diagnostic Implications of Position:

- Upper lobe nodules with a history of smoking or systemic symptoms are more concerning for malignancy or TB.

- Lower lobe nodules in patients with risk factors for aspiration or systemic infections (e.g., immunosuppression) are more likely infectious or inflammatory.

- Multiple nodules in specific regions (e.g., perilymphatic in sarcoidosis or random in metastasis) further refine the differential diagnosis.

- Common Causes:

- upper lung predominance

- Character:

- Calcifications:

- Central,

- laminated,

- popcorn-like (benign), or

- eccentric (malignant).

- Enhancement: Malignant nodules often show significant contrast uptake (>15 HU).

- Calcifications:

- Chest X-ray:

- Appears as a well-defined, round opacity; small nodules may not be detected.

- PET-CT:

- High SUV uptake (>2.5) suggests malignancy.

- False positives can occur with infectious or inflammatory nodules.

- Chest CT (preferred):

- Differential diagnosis

- Infection:

- Granulomas (e.g., tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis).

- Pulmonary abscess (in early stages).

- Inflammation:

- Rheumatoid nodule.

- Sarcoidosis.

- Neoplasm:

- Benign: Hamartoma.

- Malignant: Primary lung cancer (e.g., adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma), metastases.

- Mechanical: Rounded atelectasis.

- Circulatory: Pulmonary infarct (may mimic a nodule).

- Idiopathic: Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP).

- Iatrogenic: Post-radiation fibrosis with nodule formation.

- Infection:

- Recommendations:

- Further evaluation:

- Low-dose chest CT for characterization and follow-up.

- PET-CT for nodules ≥8 mm with suspicious features.

- Biopsy (CT-guided or bronchoscopic) for indeterminate or enlarging nodules.

- Surveillance:

- Follow-up intervals based on nodule size and risk factors per guidelines (e.g., Fleischner Society).

- Further evaluation:

- Key considerations and pearls:

- Nodules <8 mm are often benign but require surveillance in high-risk individuals.

- Calcifications and fat within a nodule strongly suggest benign etiology (e.g., hamartoma).

- Spiculated margins, rapid growth, and high SUV uptake are concerning for malignancy.

- Clinical history (e.g., smoking, prior malignancy, exposure to infectious agents) is essential for guiding the differential diagnosis.

Solid pulmonary nodule: These nodules appear as well-defined, dense lesions with a uniform density throughout. They can be benign or malignant.

Multiple pulmonary nodules: Sometimes, more than one nodule can be present in the lungs. These can be caused by various conditions such as metastases from cancer or infectious diseases.

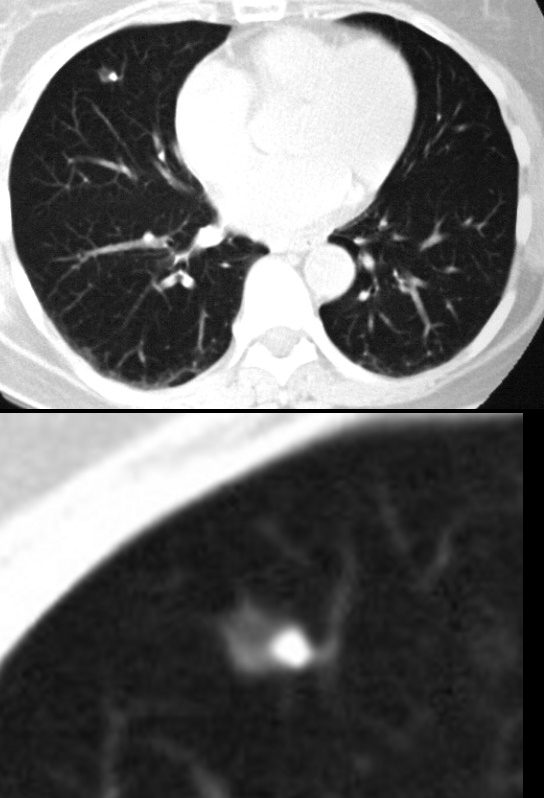

The lower panels demonstrate centrilobular distribution of someof the nodules

Ashley Davidoff MD

TheCommonVein.net

134336c

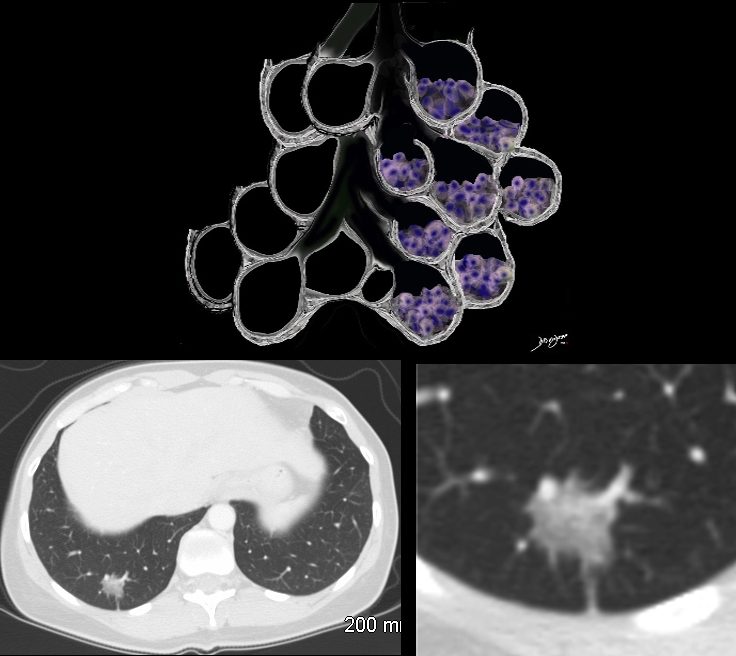

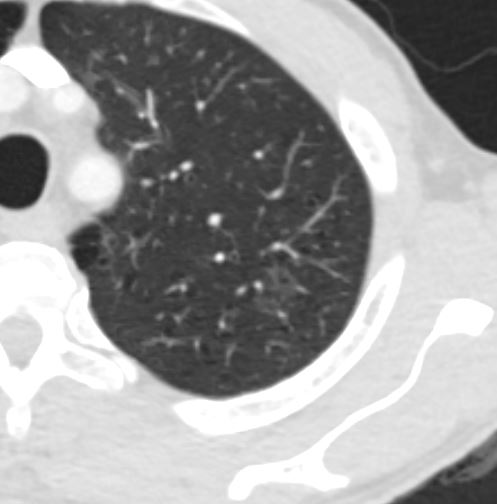

Ground-glass opacity (GGO): GGO appears as hazy, increased lung density that does not obscure the underlying bronchial structures. It can be a sign of various conditions, including early-stage lung cancer or inflammation.

1 year prior

Ashley Davidoff MD

TheCommonVein.net

-

- Ground Glass Opacity and Adenocarcinoma with Lepidic Growth

The Ground Glass Opacity (GGO) in this case is caused by partial filling of the alveolus with malignant cells Ground glass opacification may be caused by partial filling of the alveolus with cellular material resulting in partial replacement of air with solid material. The net density is gray rather than white in the situation where the alveolus is fully replaced with cells or fluid. There is blending of the black of the subtending airways and the white of the vessels with the gray density of the cellular infiltrate and hence the normal vessels are not visualized in ground glass opacities.

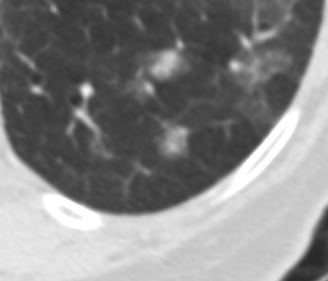

Part-solid nodule: Part-solid nodules have both solid and ground-glass components. These can also be associated with lung cancer, particularly adenocarcinoma.

Ashley Davidoff

TheCommonVein.net

Calcified nodules:

Some lung nodules may contain calcium deposits, causing them to appear as dense spots on the CT scan. These are often benign and can result from previous infections or scarring.

-

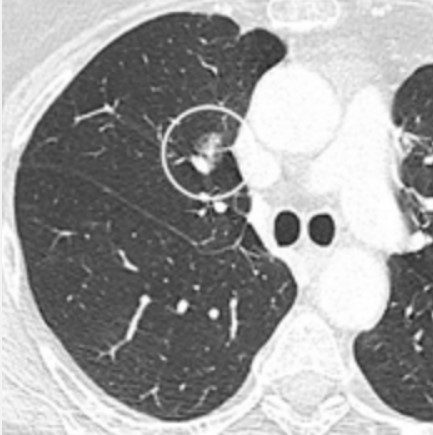

- Eccentric Calcification

-

- 56 F with a middle lobe nodule with eccentric calcification which turned out to be granulomatous in origin

-

- Ashley Davidoff

-

- TheCommonVein.net

- 30252c

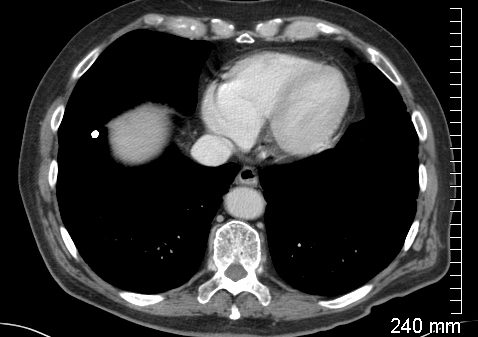

Cavitating Nodule

Pseudocavitation

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net