Nutshell

-

- perilymphatic particularly if clustered

- axial interstitium

- mid upper lung

- mediastinal and hilar adenopathy

- usually affects the bronchioles and not small airways

Upper lung field distribution

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonvein.net lungs-0774

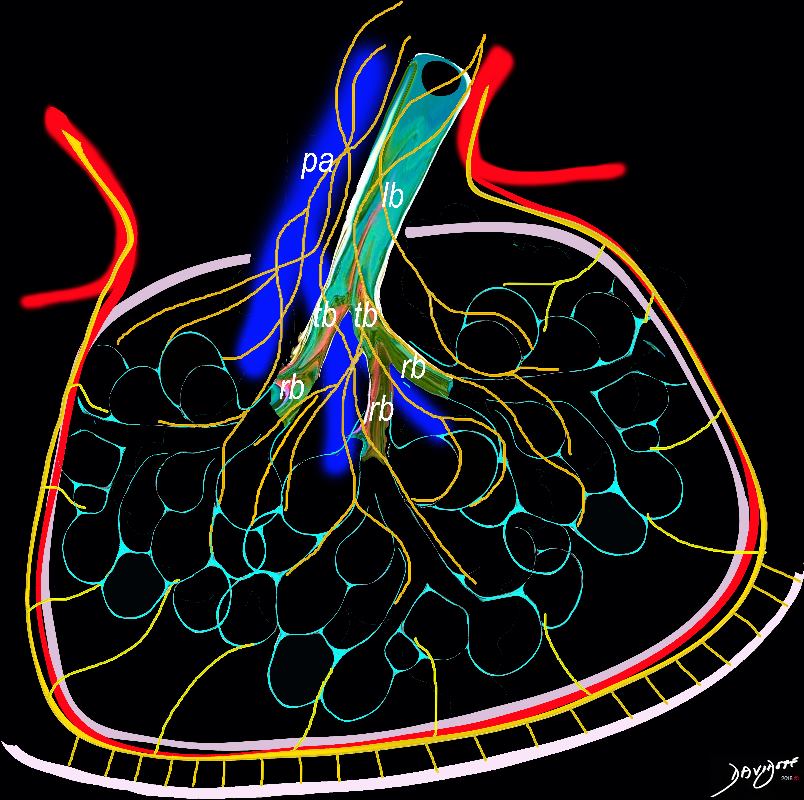

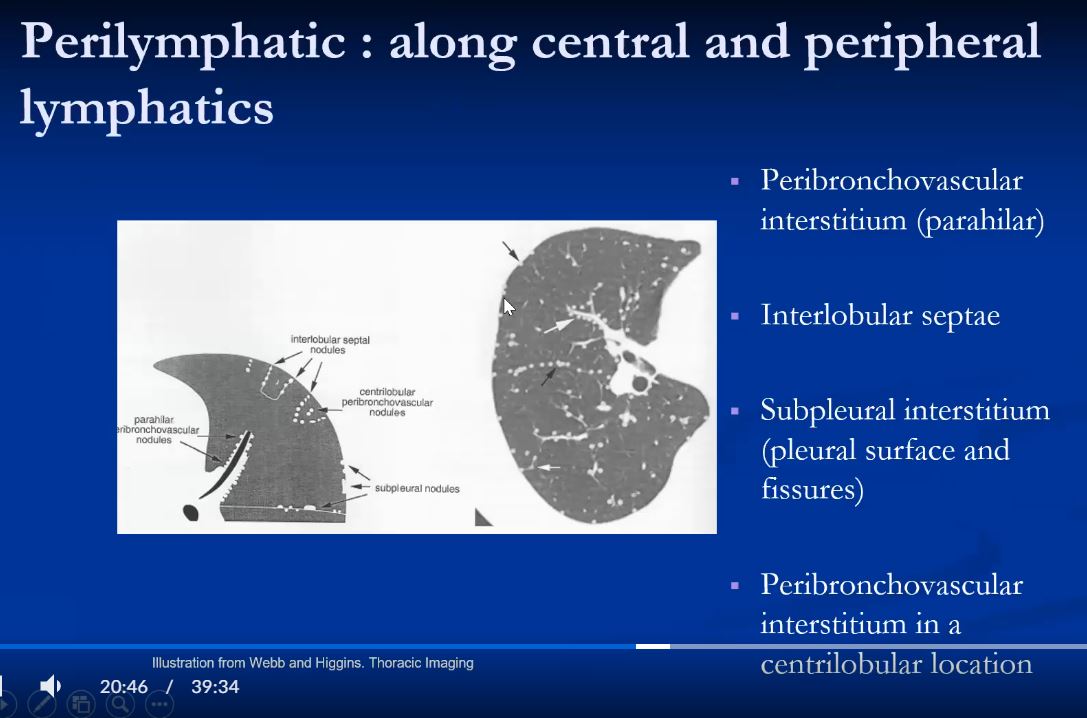

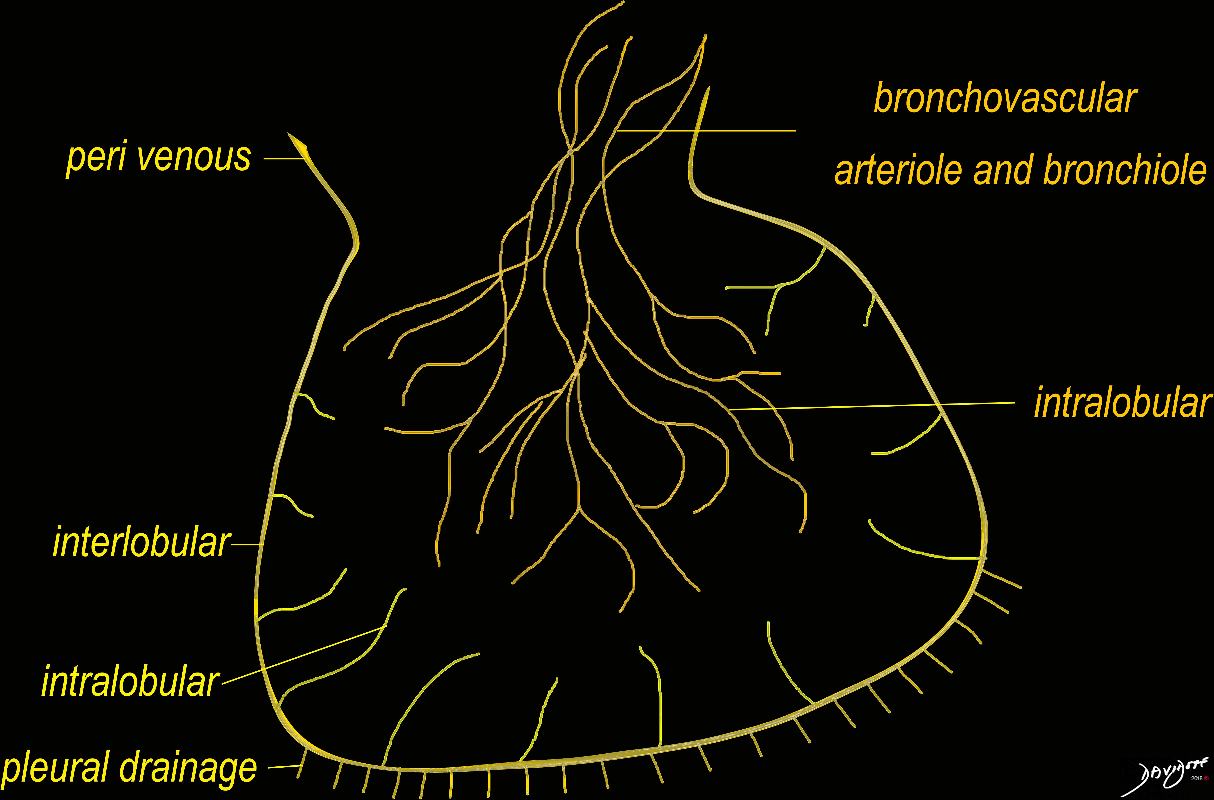

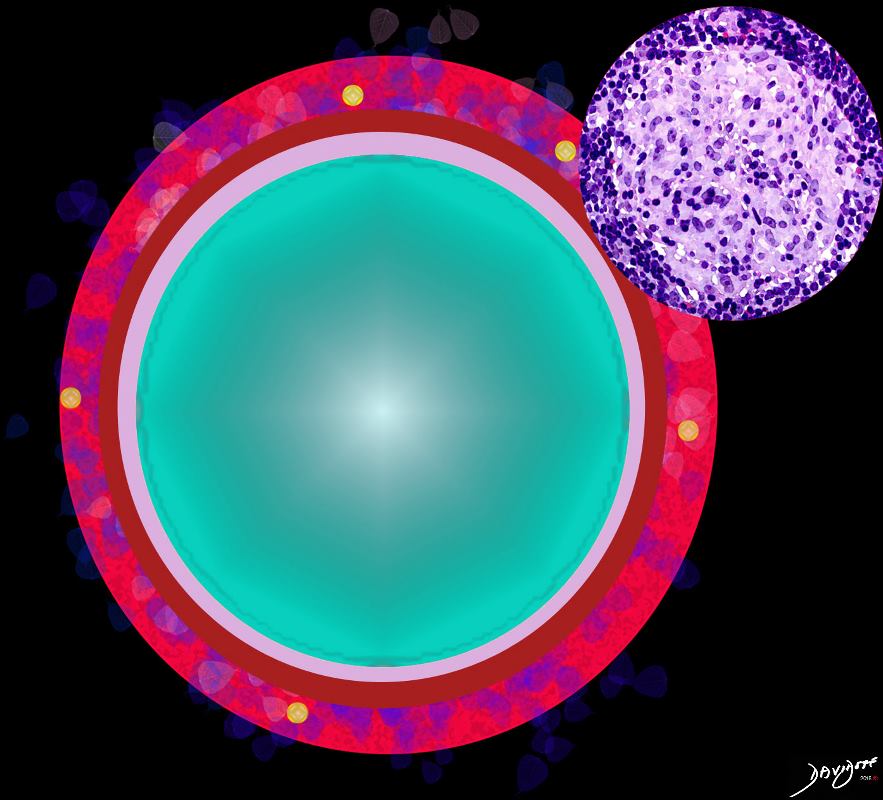

Lymphatics

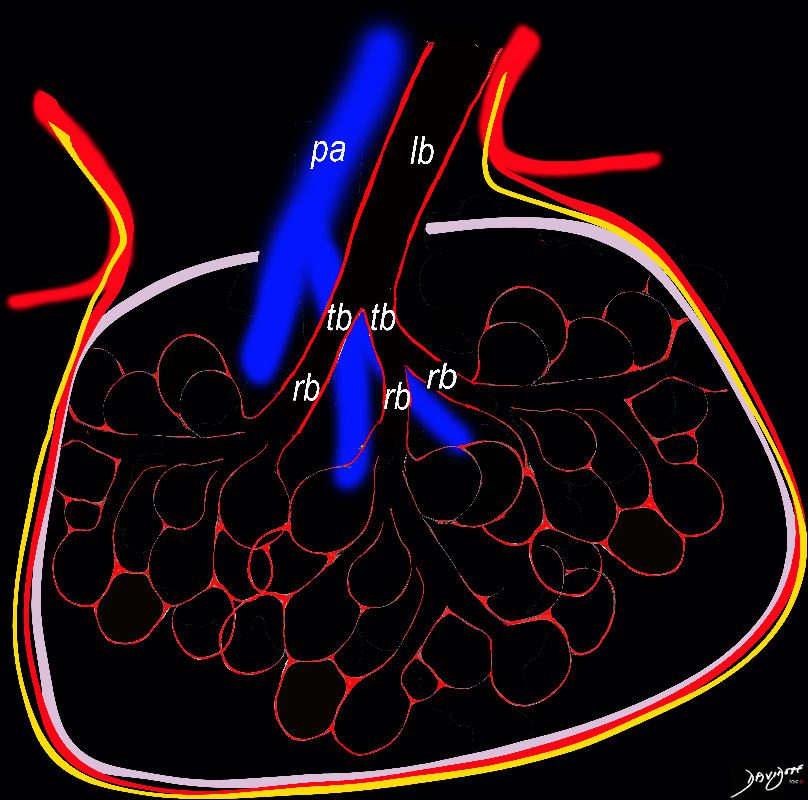

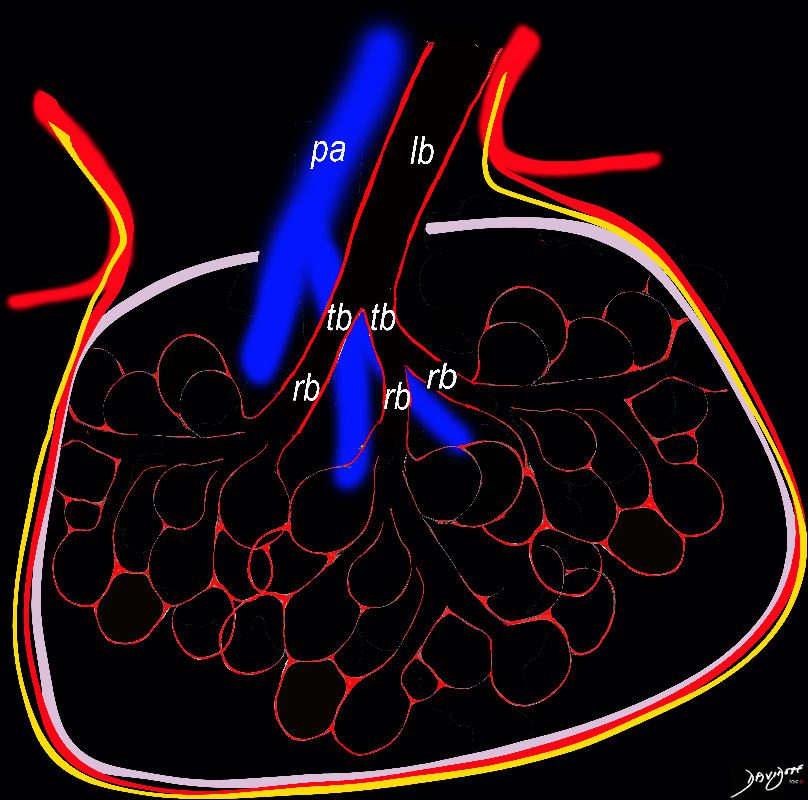

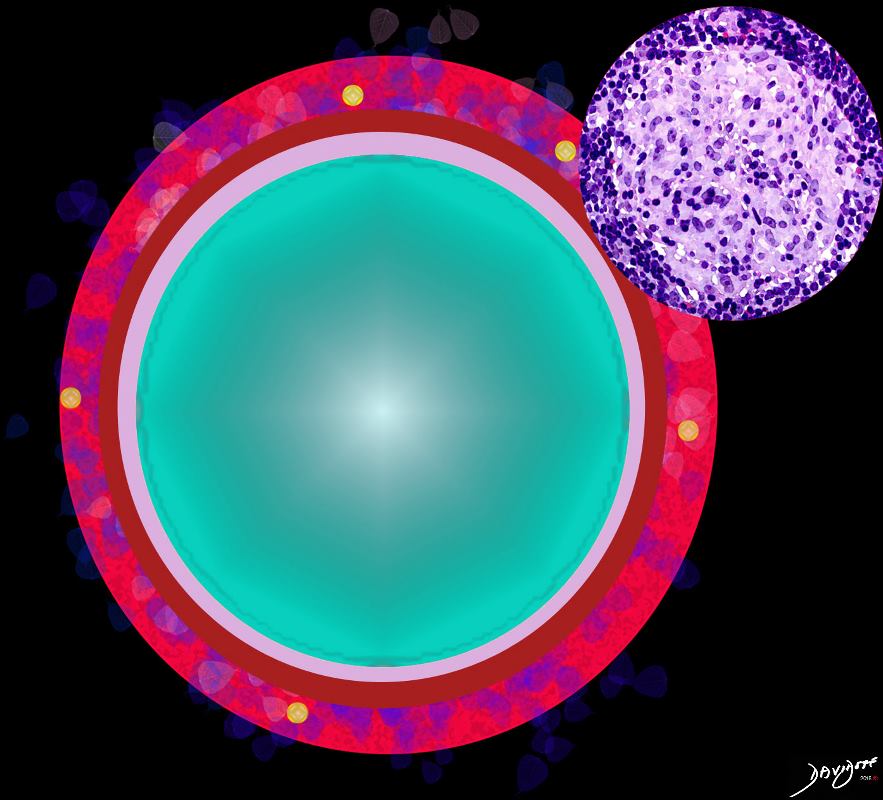

The diagram shows the 2 systems of lymphatic drainage at the level of the secondary lobule. The superficial system drains some of the interstitium of the secondary lobule, runs in the interlobular septa and drains all the pleura. Thee pathway to the lymph nodes in the mediastinum is via the pulmonary veins. The deeper system drains the interstitium in the interalveolar septa, and then they travel along the bronchovascular bundle accompanying the bronchi and pulmonary artery and into the lymph nodes of the hila and mediastinum

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net lungs-0767

Bronchioles

Ashley Davidoff MD The CommonVein.net lungs-0766

Nutshell

-

- perilymphatic particularly if clustered

- axial interstitium

- mid upper lung

- mediastinal and hilar adenopathy

- usually affects the bronchioles and not small airways

- Late

- midlung fibrosis

- honeycombing

- 90% have pulmonary involvement and only 45% are symptomatic

- interstitial disease is most common

- other pulmonary manifestations i

- pneumothorax,

- pleural thickening,

- chylothorax, and

- pulmonary hypertension

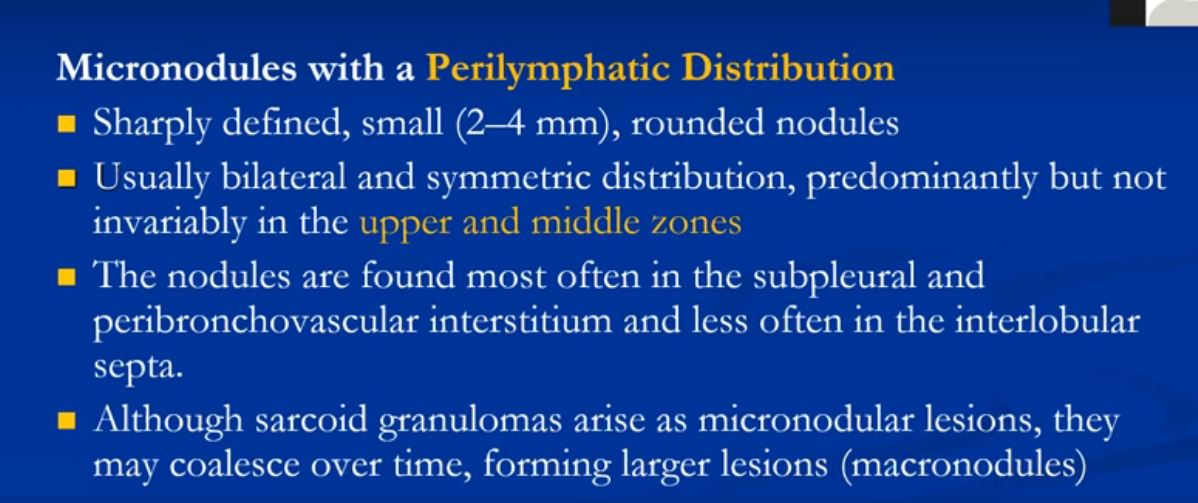

Micronodular Form of Sarcoidosis

Introduction

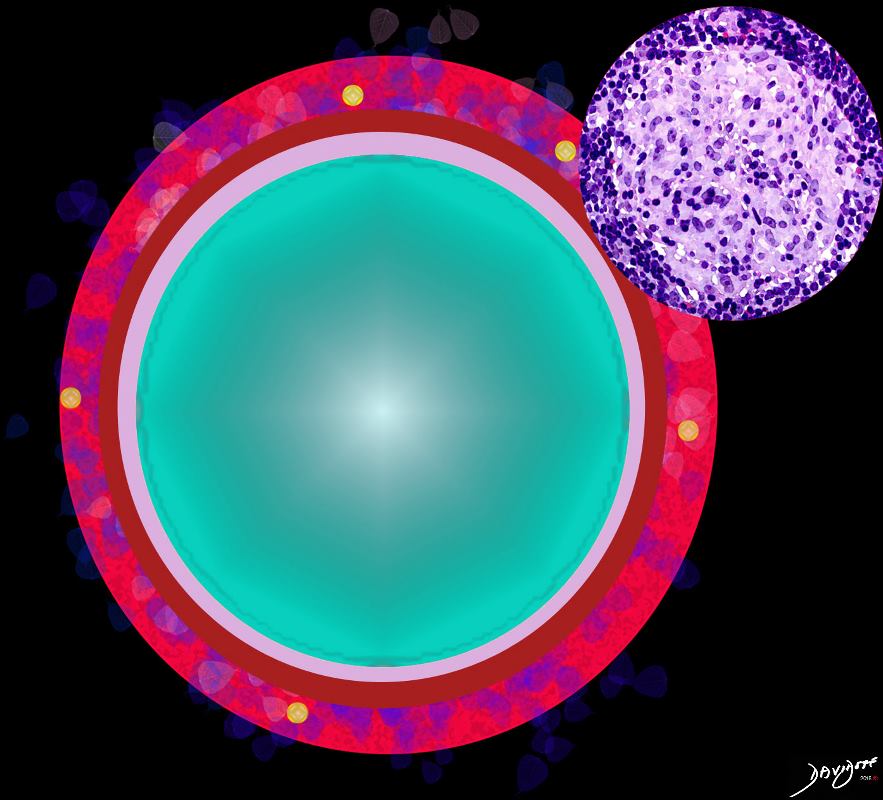

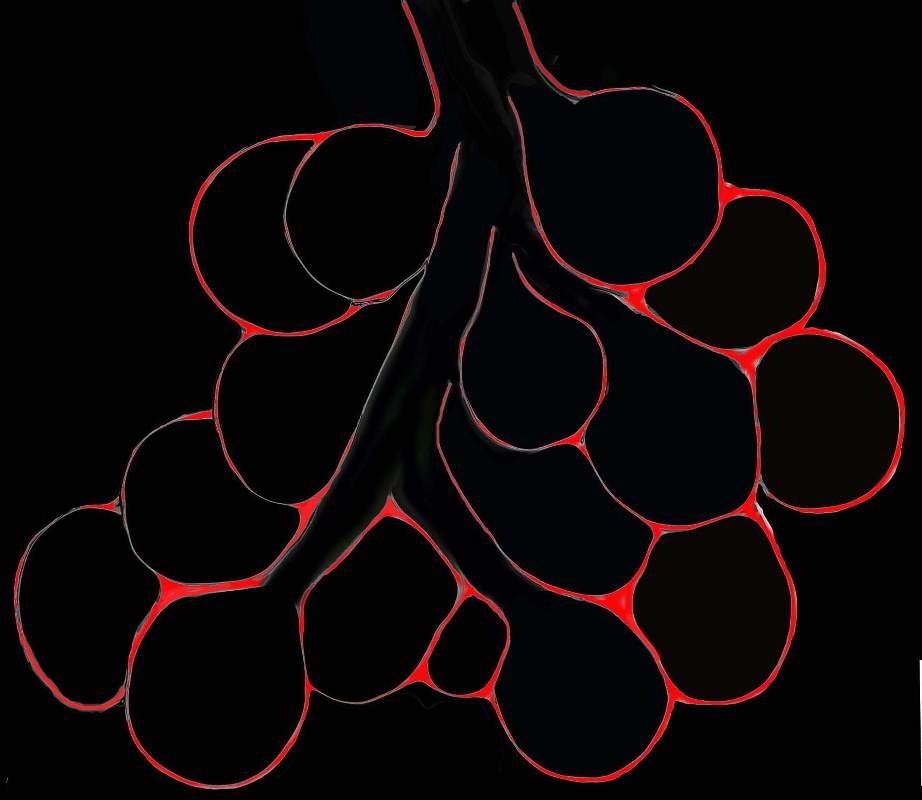

Early stages Alveolitis

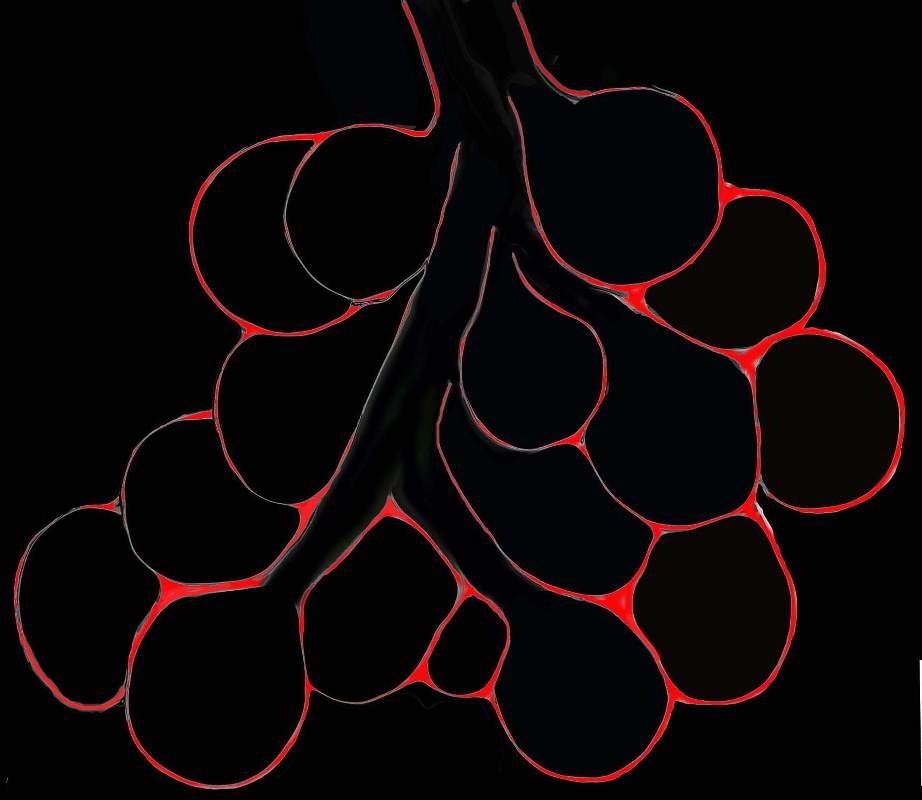

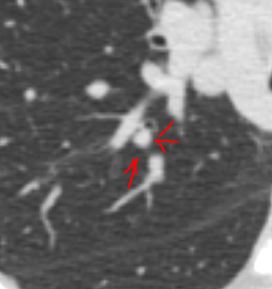

Diagram shows inflammation (red ) in the walls of the alveoli. The increased density in the interalveolar septa results in a ground glass opacity on T scan

Ashley Davidoff TheCommonVein.net

lungs-0736b

Diagram shows inflammation (red ) in the walls of the alveoli. The increased density in the interalveolar septa results in a ground glass opacity on T scan

Ashley Davidoff TheCommonVein.net

lungs-0736

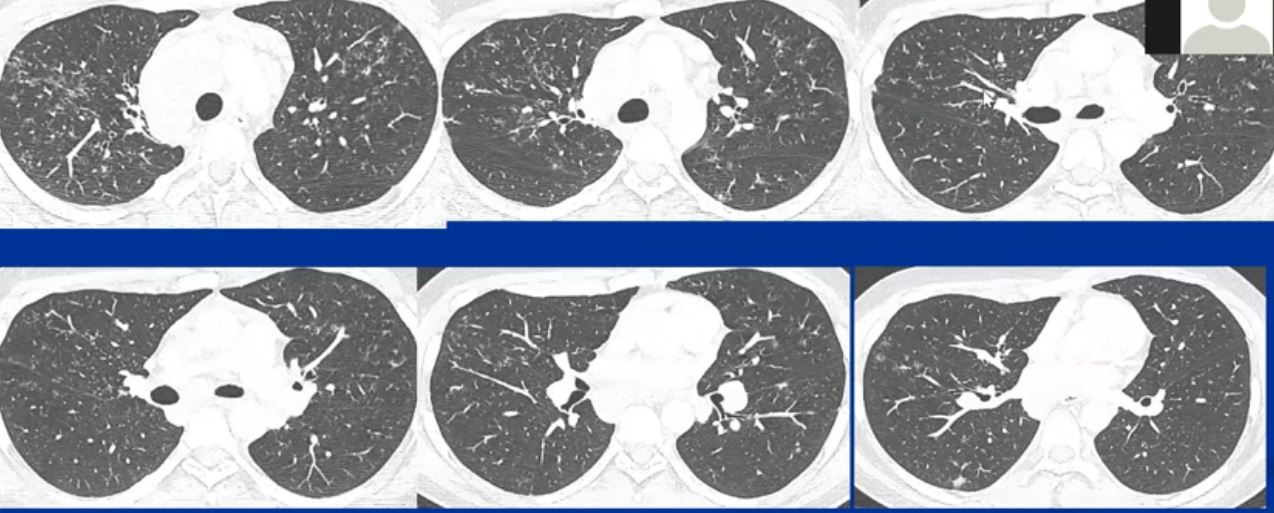

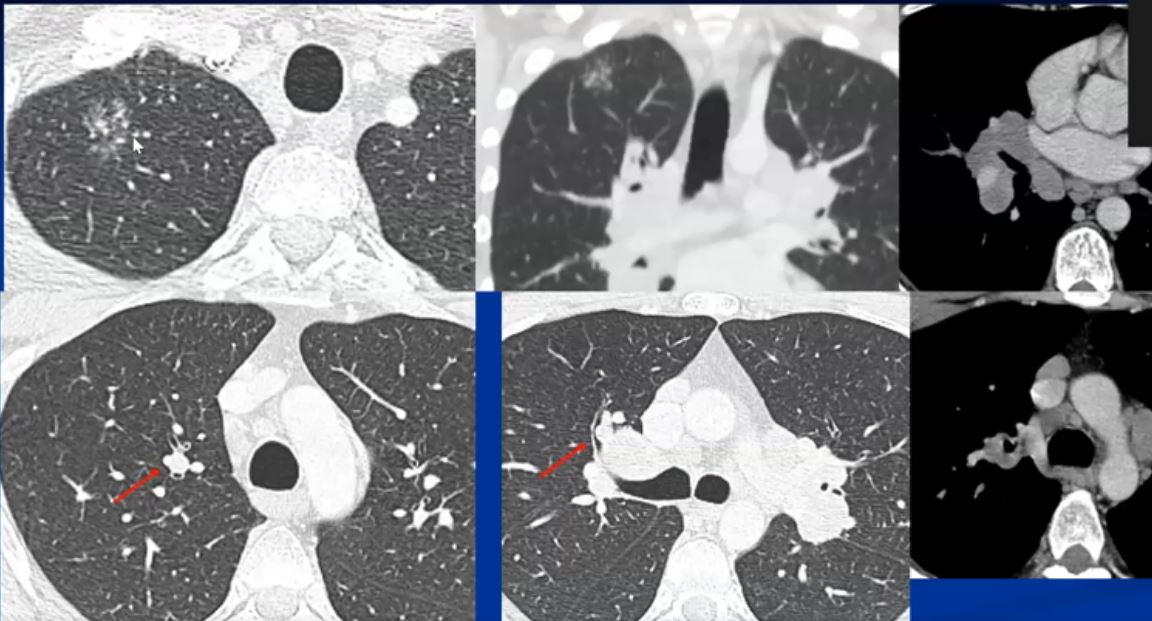

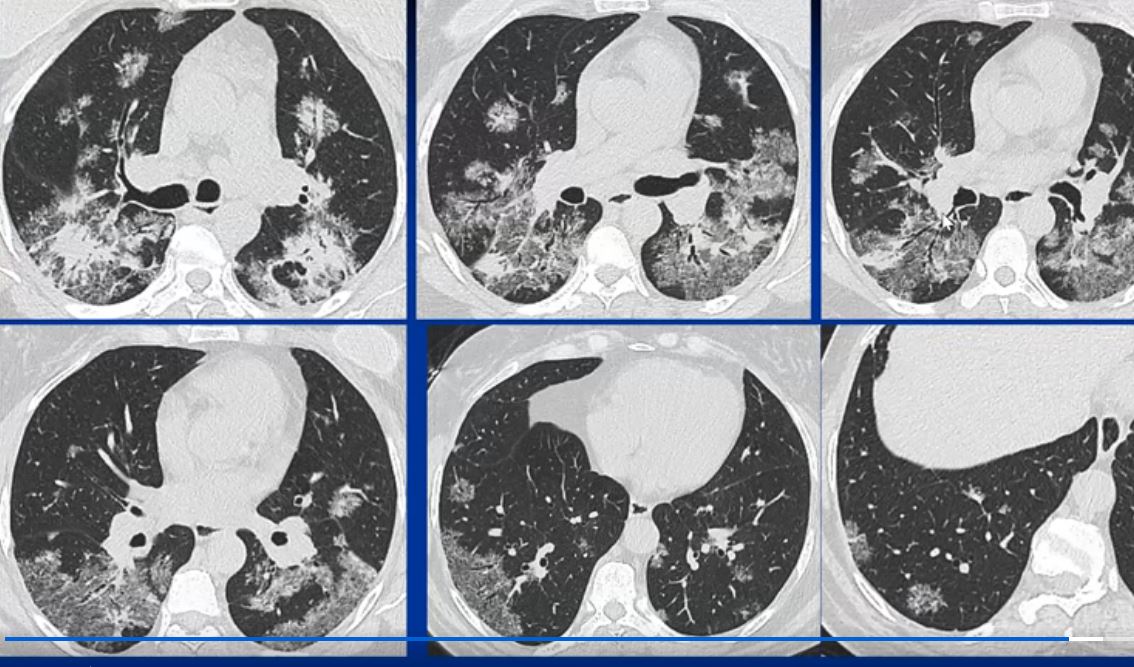

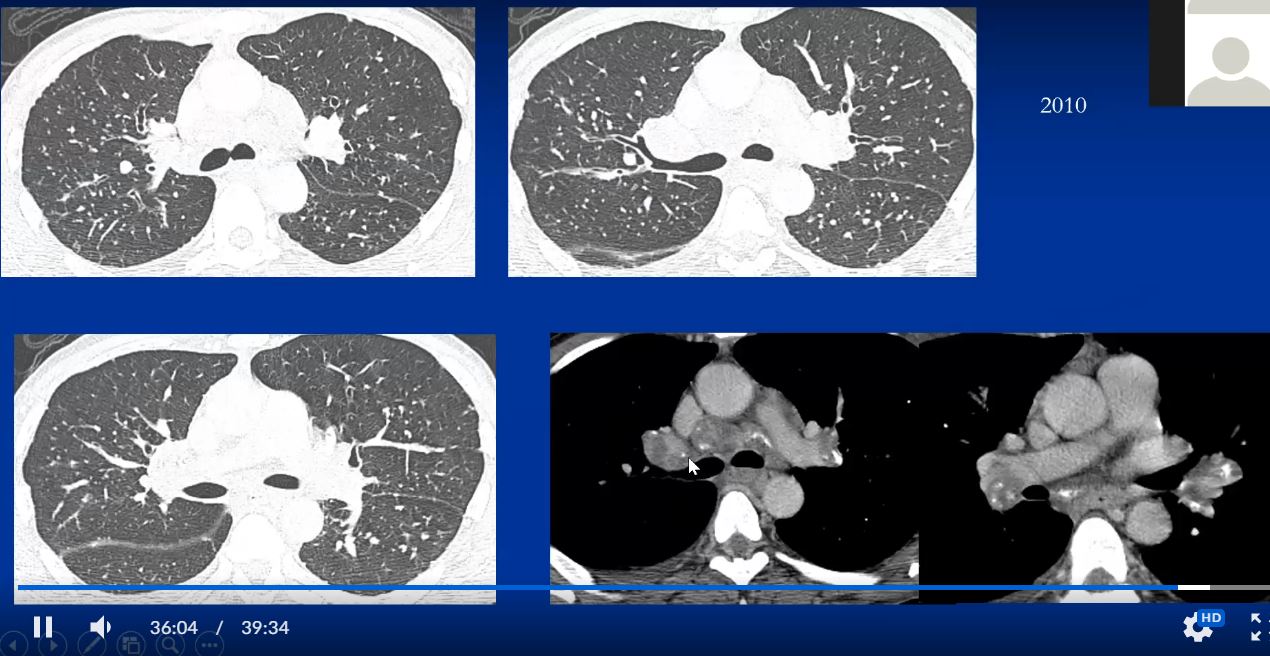

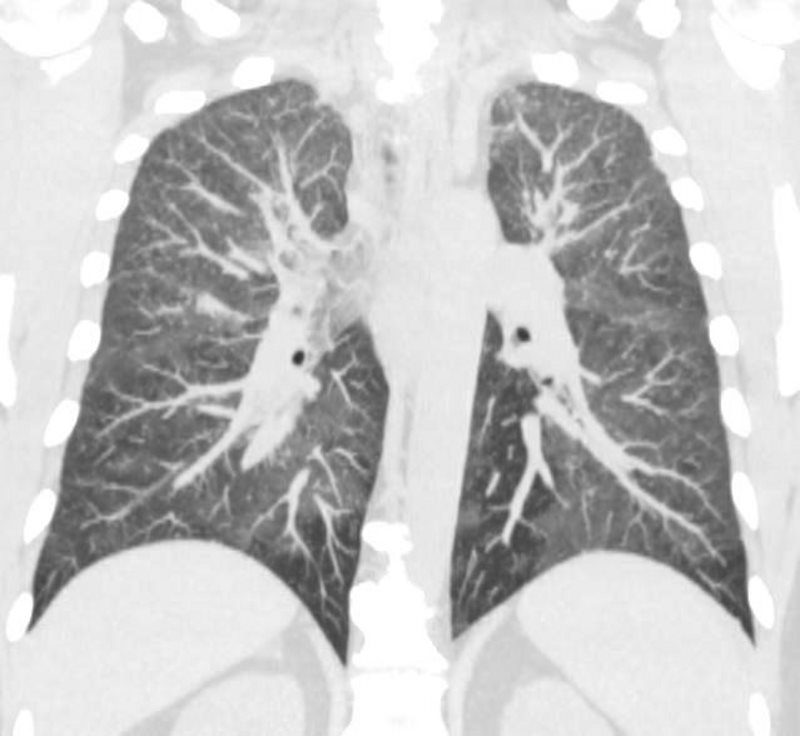

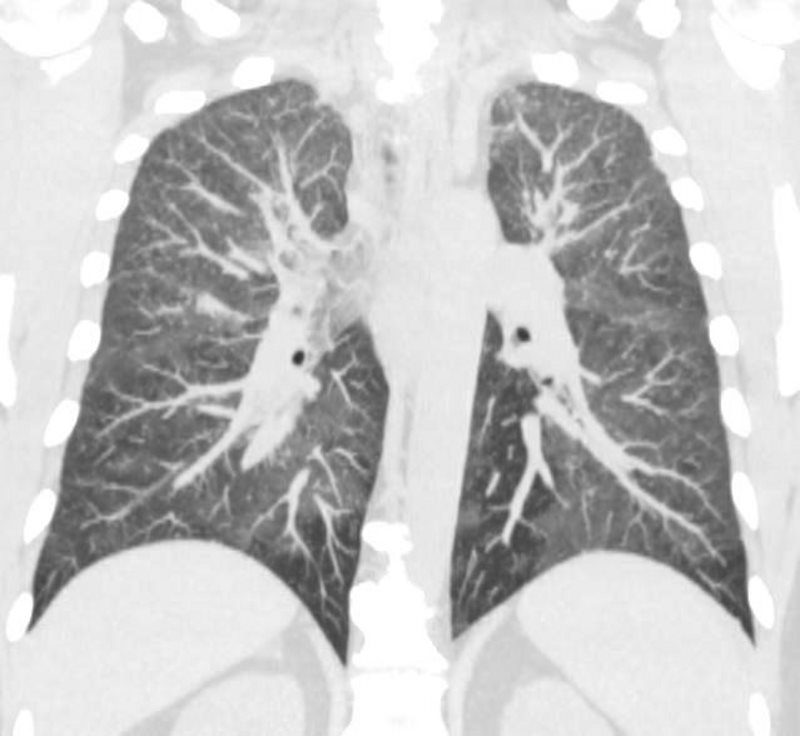

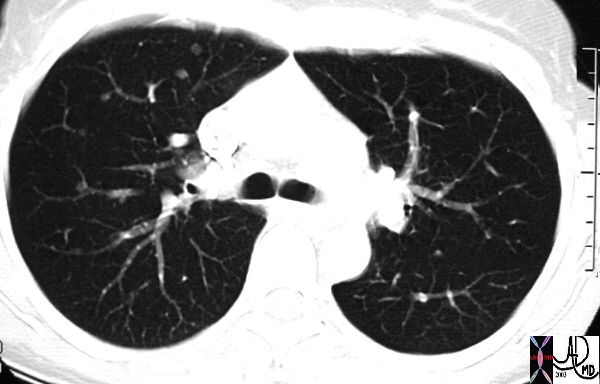

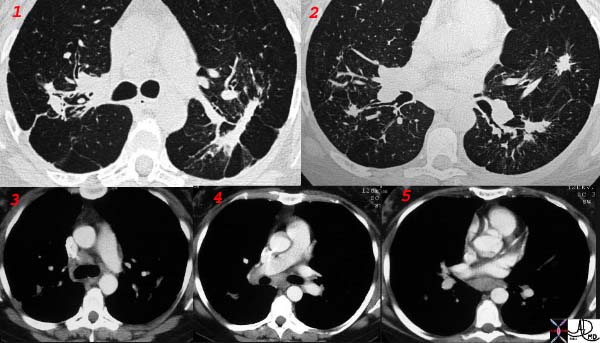

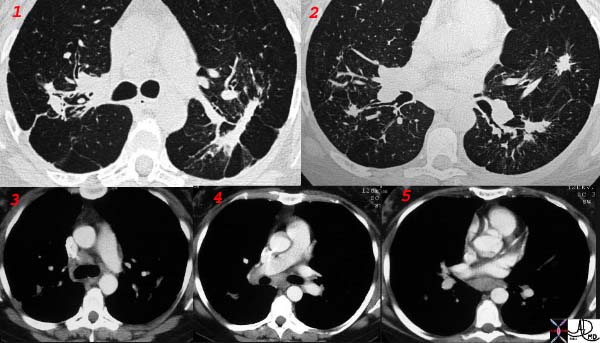

44-year-old male presents with diffuse ground glass involving the upper lobes and lesser extent the lower lobes sparing the middle lobe and lingula to some extent.

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net 29064b05.8

Ashley Davidoff MD

TheCommonvein.net

9

Ashley Davidoff MD The CommonVein.net lungs-0766

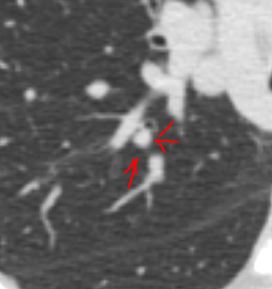

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.com sarcoidosis 003 35M

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.com sarcoidosis 001 35M

- Structurally

-

- granulomatous inflammation is

- more common in the larger airways and often

- invades

- around the airway wall

- vasculature from the outside,

- destroying the adventitia

- intimal involvement may result in

- necrotizing granuloma and

- granulomatous vasculitis.

- Pulmonary hypertension develops when the disease progresses and intimal involvement is prevalent.

- chronic sarcoidosis increases the occurrence of

- pulmonary fibrosis and

- honeycombing,

-

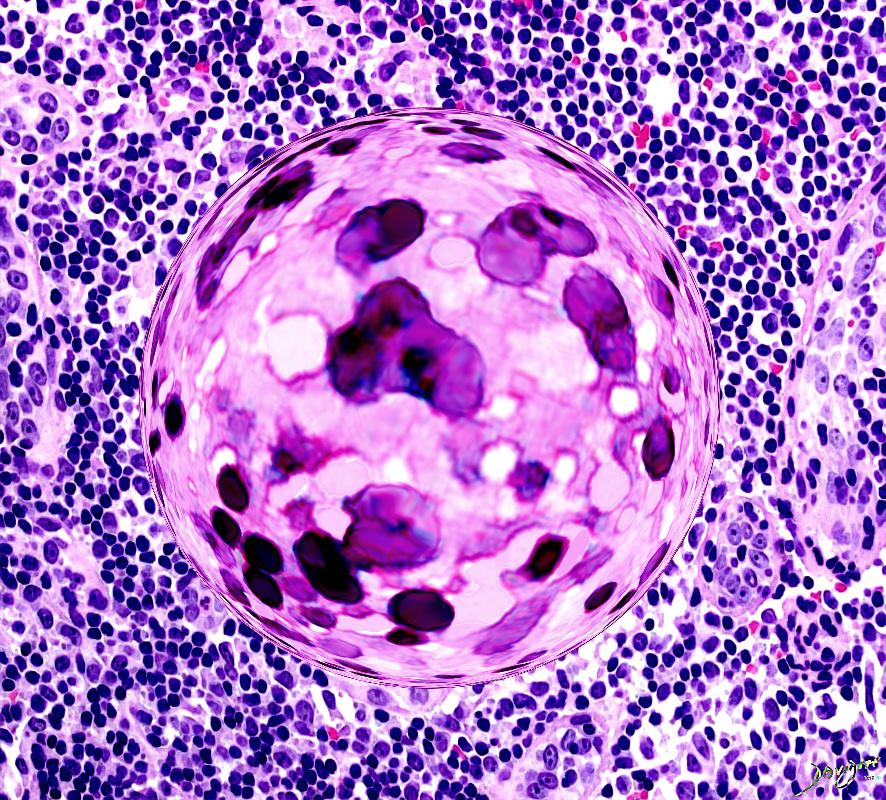

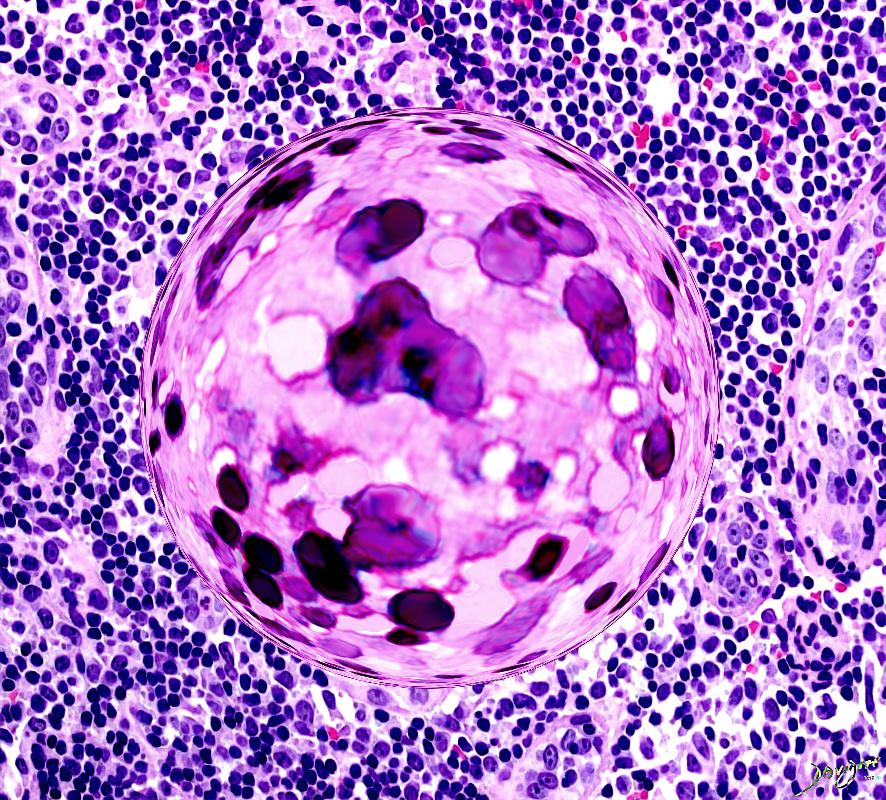

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem non caseating granulomatous disorder of unknown etiology that affects people of all ages and races. The etiology of sarcoidosis is still unknown, but is thought to to be related to an environmental antigen.

|

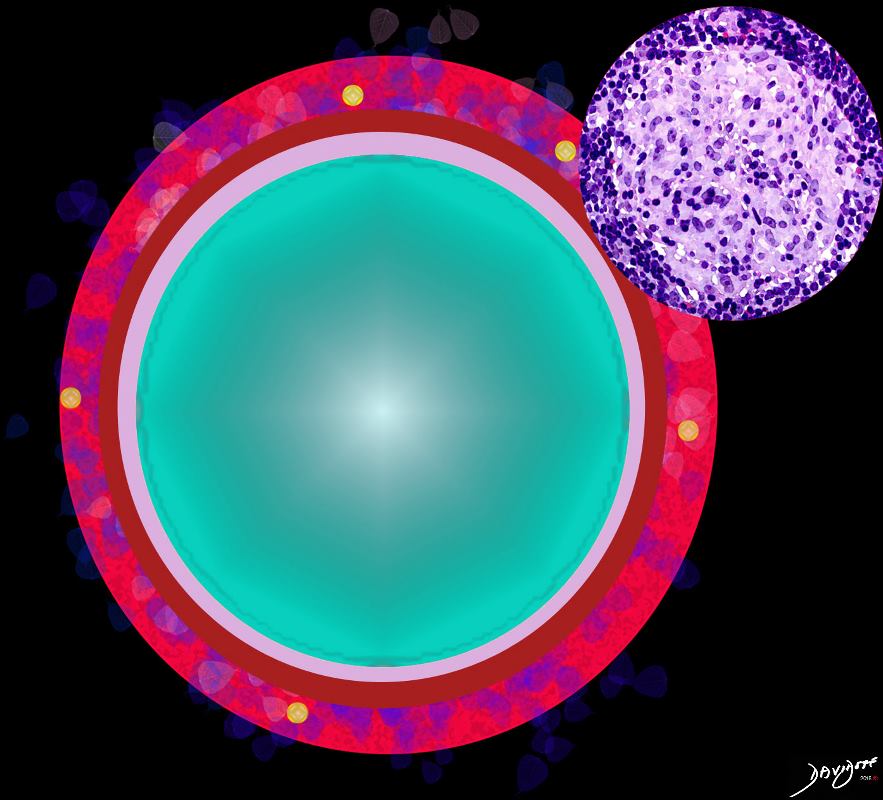

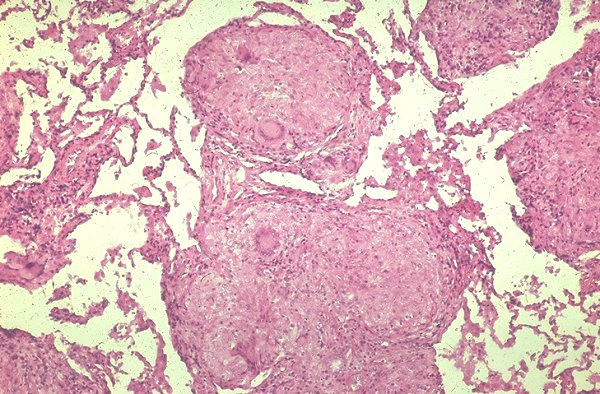

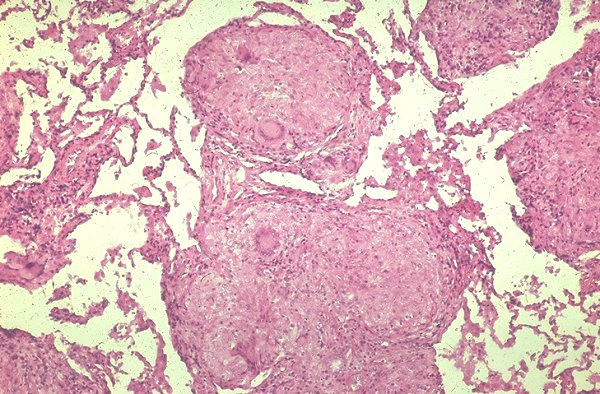

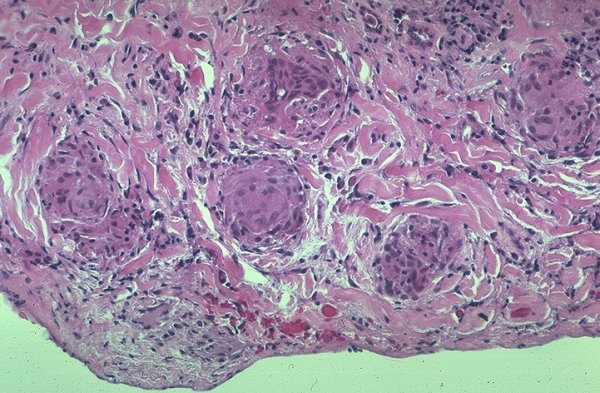

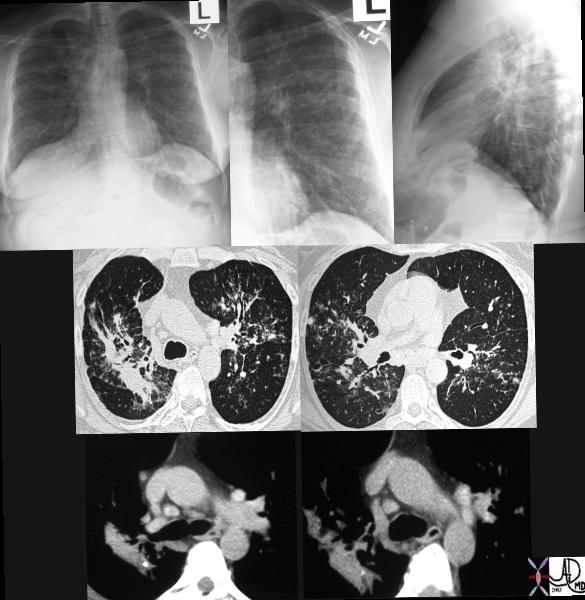

Confluent granulomas forming a nodule in a patient with sarcoidosis. Courtesy Yale Rosen MD. 54448

The disease is characterized pathologically by the presence of noncaseating granulomas in involved organs. Any organ can be affected but the lungs and lymph nodes are the most common. The granulomas cause structural distortion and as a result associated functional disorder. The clinical presentation ranges from asymptomatic disease to progressive multisystem debilitation. Most patients are asymptomatic and many patients have spontaneous regression.

The diagnosis rests on the histological findings of non caseating epithelioid granulomas. No combination of radiographic and clinical findings is pathognomonic. Sarcoidosis is a diagnosis of exclusion based on combined radiologic, clinical, and histologic data. When treatment is indicated the mainstay is corticosteroids

Etymology

from Gk. sarx (gen. sarkos) = “flesh.” + oid = “like” aka Lofgren’s syndrome; sarcoid of Boeck; Schaumann’s disease aka Boeck’s sarcoid Besnier-Boeck disease; Hilar adenopathy plus uveitis;

Overview

BASIC PROCESS

is an over-exuberant inflammatory reaction by the cellular immune system to an antigen, resulting in a chronic, non caseating, granulomatous, multisystem inflammatory disorder

CAUSE

A single identifiable causative agent for sarcoidosis has not been isolated. Environmental antigens and agents including infectious agents (mycobacteria, mycobacterial L forms, spirochetes, herpes type 8 and Whipple’s agent) as well as beryllium and organic antigens e.g., pine pollen, peanut dust, and inorganic dusts have been implicated.

The cause is probably multifactorial including age, population group and genetic makeup. It has peak incidence in the 20-40 year old age group and African Americans and Swedes have a relatively high predisposition.

RESULT

The disease is characterized pathologically by the presence of noncaseating granulomas in involved organs. Any organ can be affected but the lungs and lymph nodes are the most common.

The granulomas cause structural distortion and as a result associated functional disorder. They may resolve completely or proceed to fibrosis. The clinical presentation ranges from asymptomatic disease to progressive multisystem debilitation. Fever, weight loss, and arthralgias may occur initially. Skin lesions are common. Peripheral lymphadenopathy is important to identify since the nodes represent easy access for biopsy and histological diagnosis. The alternative is transbronchial biopsy.

DIAGNOSIS

Misdiagnosis occurs with regularity. Sarcoidosis is a great mimicker and the diagnosis is often elusive. No combination of radiograph and clinical findings is pathognomonic but chest x-ray and pulmonary function tests are the most useful initial diagnostic tools;

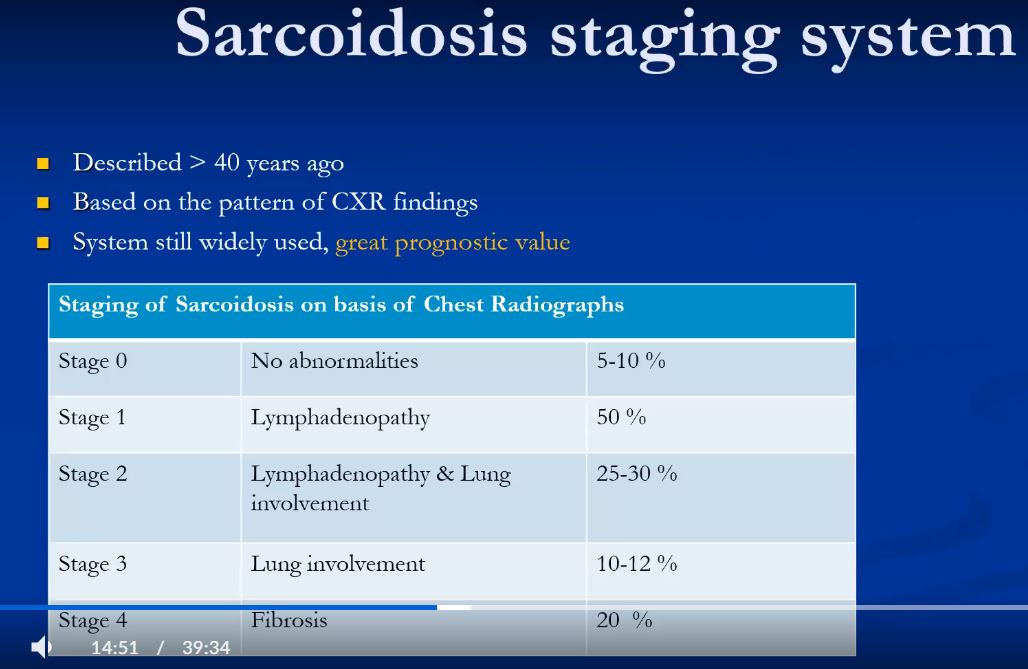

Chest x-ray abnormalities occur in 90% of patients, characterised by bilateral and often right paratracheal adenopathy. The disease has been graded according to the CXR dividing the disease into normal, (stage 0) isolated adenopathy, (stage 1) adenopathy and parenchymal disease, (stage 2) isolated parenchymal disease, (stage 3) permanent fibrosis. (stage 4) CT and particularly high resolution CT has been useful in differentiating between reversible granulomatous disease and and irreversible fibrotic disease. The association of the granulomas with the lymphatic system, the predilection to the upper lobes, with an axial distribution along bronchovascular lines are characteristic.

There is no single serum test that is reliable. The Kveim test is not used anymore because of FDA restriction and ACE levels are non specific.

The diagnosis rests on the histological findings of non caseating epithelioid granulomas.

Sarcoidosis is a diagnosis of exclusion based on combined radiologic, clinical, and histologic data.

TREATMENT

The vast majority of patients recover or are minimally symptomatic without treatment, (80%) and many do not have relapses. The decision to treat remains enigmatic because of the condition’s uncertain origin, variable course and natural history, and the unreliable response to steroids. In many symptoms are absent or mild, and in some there is spontaneous regression. Treatment is absolutely indicated when there is uveitis. When treatment is indicated the mainstay is corticosteroids.

Principles

In this section we attempt to apply the universal principles of disease in order to place this disease in perspective and to promote a basic understanding of the disease.

Sarcoidosis is

an inflammatory disorder with structural changes characterised initially by granulomatous inflammation and subsequently by fibrosis.

In the acute phases the inflammatory component will manifest variably with a variety of the original principles put forth by the Roman encyclopedist Celsus in the 1st century A.D. – Aulus (Aurelius) Cornelius. He was a physician and medical writer, who lived from about 30 B.C. to 45 A.D.

calor (heat warmth)

dolor (pain)

tumor (swelling)

rubor (redness)

Laesio functio- (loss of function) was a fifth component that was later added to Celsius principles

PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL PRINCIPLES OF INFLAMMATION

Inflammation has multiple facets:

1)RESPONSE TO THE ANTIGEN

a)SPECIFIC RESPONSE

T lymphocytes and immunoglobulins

b)NON SPECIFIC RESPONSE

Neutrophils, eosinophils monocytes and tissue macrophages

Alternative complement pathway

Hageman factor (coagulation cascade)

2)AMPLIFICATION

Complement

arachidonate products

mast cell products

platelet activating factors

bradykinin

serotonin

coagulation cascade

cytokines (IFN TNF IL-1 IL-6 IL-8 IL-11, chemokines

growth factors,)

lysosomal contents of neutrophils

3) ANTIGEN DESTRUCTION

neutrophils eosinophils macrophages cytotoxic lymphocytes

terminal complement components reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates

CLINICAL EFFECTS OF INFLAMMATION

The acute component of granulomatous cellular disease is not as severe as it might be with a pneumococcal infection for example and so the resulting clinical manifestation is relatively blunted. Systemically this may translate into fever malaise anorexia and weight loss. Depending on the location of the illness, (most commonly in the lungs) it may cause irritation (cough), or loss of function – dyspnea for example.

GRANULOMATOUS COMPONENT

A granuloma is an aggregation of macrophages having an enlarged squamous like appearance (epitheloid macrophages) assuming a nodular configuration, and surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes. It thus occupies space and replaces normal functioning tissue. It may also cause irritation and a cough as a result, or if extensive may als cause dyspnea.

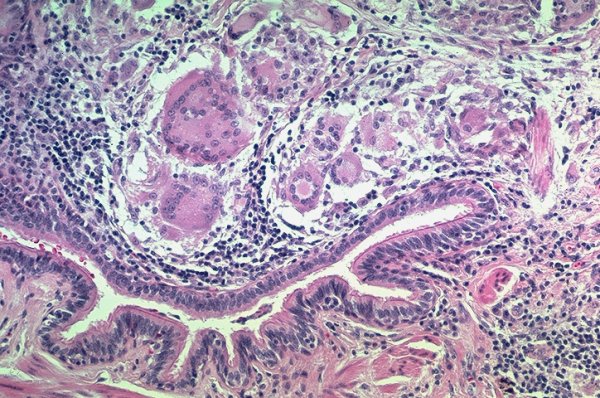

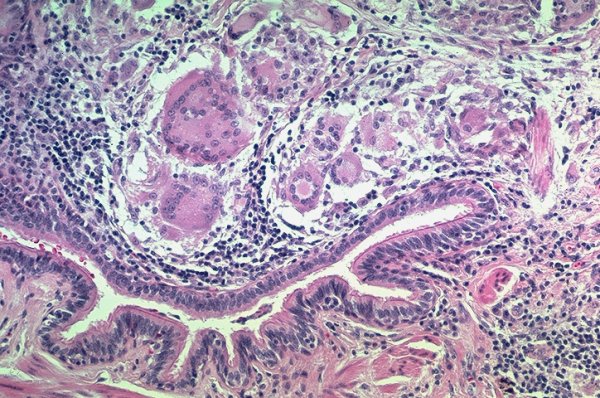

Granulomas involving a bronchiole in a patient with sarcoidosis. Courtesy Yale Rosen MD. 54450

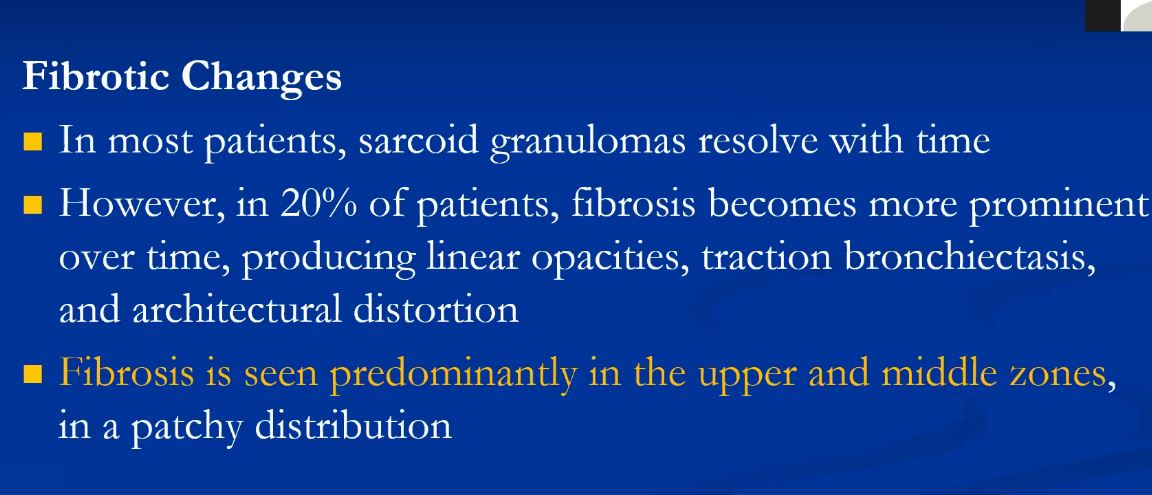

FIBROSIS.

Fibrotic disease causes structures to distort and harden and this aspect may result in irreversible replacement of normal functioning lung, leading to narrowing of some of the tubular structures and ectasia of others. Bronchiectasis cystic change and honeycombing are well known complications. Distortion may result in poor pulmonary toilet, with accumulation of secretions and loss of local defence mechanisms and hence secondary infection by aspergillus for example.

The loss of elasticity of the tissues caused by fibrosis leads to restrictive lung disease.

Historical Aspects

The initial description of sarcoidosis in 1877 is credited to an English physician, Jonathan Hutchinson.

In 1899, Dr Caesar Boeck, independently described a case of cutaneous lesions. He coined the phrase sarcoid, because his impression was that the lesions resembled sarcoma but were in fact benign. (from the Greek words “sark” and “oid,” meaning flesh-like) Histologically they were characterised by epithelioid cells and giant cells.

|

The initial description of sarcoidosis in 1877 is credited to an English physician, Jonathan Hutchinson. (1828-1913). Reference http://clendening.kumc.edu/dc/rm/19_134p.jpg 54453 This image may be copyrighted code historical

Sarcoidosis is characterised by the presence of lymphadenopathy in the hila and azygos region reminiscent of the triad of the pawnbrokers sign and the Medici arms. The Medici arms were characterised by either 3 balls or multiples thereof. These balls were thought to be the origin of the pawnbrokers sign of three balls. The Medici family were benefactors of the arts in Florence in the early 15 century, and were a major influence in the growth of art in the early Renaissance period.

Classification

BASED ON ANATOMICAL LOCATION

Sarcoidosis of

lung

lymph nodes

lung with sarcoidosis of lymph nodes

skin

Sarcoidosis of other and combined sites

Iridocyclitis in sarcoidosis

Multiple cranial nerve palsies in sarcoidosis

Sarcoid arthropathy

Sarcoid myocarditis

Sarcoid myositis

Uveoparotid fever

BASED ON FUNCTIONAL ASPECTS

asymptomatic

restrictive impairment

obstructive impairment

BASED ON THE CXR

Stage 0 – No radiographic abnormality ( 5% )

Stage I – Thoracic lymphadenopathy. Normal lung parenchyma. ( 50% )

Stage II – Hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Abnormal lung parenchyma. ( 30% )

Stage III – Abnormal lung parenchyma. No lymphadenopathy. ( 15% )

Stage IV – Permanent lung fibrosis. ( 20% )

Statistics

Prevalence of Sarcoidosis:

estimated population of people who are managing disease at any given time.

20 per 100,000 overall;

5 in 100,000 white people;

40 out of 100,000 black people;

range in various populations <1 to 64 per 100,000 worldwide

Irish females living in London 200/100,000 (an anomaly worth observing as to what may be the cause)

Scandinavia 64 /100,000

France 10/100,000,

Poland 3/100,000,

rare in the Inuit, Canadian Indians, New Zealand Maoris, and Southeast Asians.

Prevalance Rate:

approx 1 in 5,000 or 0.02% or 54,400 people in USA

Incidence (annual) of Sarcoidosis: annual diagnosis rate, or the number of new cases of Sarcoidosis diagnosed each year.

20 per 100,000 in the city, less in the country.

Incidence Rate: approx 1 in 5,000 or 0.02% or 54,400 people in USA

Deaths from Sarcoidosis: 572 deaths (NHLBI 1999)

ratio of blacks to whites ranging from 10:1 to 17:1.

In Europe, however, the disease affects mostly whites.

|

This is an image of a flautist in New Orleans. The African American population has a relatively high incidence of sarcoidosis. Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD. 60165

There is a familial history in 15 % of cases

Age-adjusted annual incidences in the USA among blacks is 35.5 per 100,000 and in whites is and 10.9 per 100,000.

The global prevalence has been estimated as approximately 10-40 in 100000.

Geographic Distribution

The disease is relatively common in northern Europe and especially in Great Britain Ireland and Scandinavia. It is also common in North America and Japan.

USA

In the USA, of particular interest is the high incidence in African American population compared to the white population. Age-adjusted annual incidences reported are 35.5 and 10.9 per 100,000.

In the world however nearly 80% of affected patients are white.

Familial sarcoidosis is more common in blacks than in whites. Several factors are associated with a worse prognosis, including black race.

In most counties the peak age is 20-30’s whereas in Sweden and Japan, a second peak in incidence has been noted in middle age, especially in women.

The low incidence countries include China, India, and Russia, as well as the continent of Africa. The prevalence of other granulomatous disease worldwide such as tuberculosis and leprosy may result in under diagnosis of sarcoidosis, and the true incidence of the disease in “low incidence” countries is questioned.The disease incidence is highest in US black and Scandinavian populations, while it appears to be less common in US white, Japanese, Indian, Spanish, or South American populations. In some countries, like Japan and Italy it is more common in the south than the north raising the suspicion that climate may have some bearing in the pathogenesis of the disease.

Genetics

The cause of sarcoidosis is not known but it is thought to have an immunological origin. Genetic factors may contribute to susceptibility to the initiating antigens.

Familial sarcoidosis has been identified in approximately 15% of patients and is more common in blacks than in whites. The angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) genotype may be an important factor in the determination of susceptibility and progression of sarcoidosis in African Americans in contrast to the Caucasian population.

Sex Distribution

Women are affected slightly more often than men.

Women are more likely to have eye and neurologic involvement, erythema nodosum and to be over 40 years.

Men are more likely to be hypercalcemic to have skin involvement (other than erythema nodosum) liver, bone marrow, and extrathoracic lymph node involvement.

Age

Sarcoidosis presents in patients between 10 to 40 years of age in 70 to 90 percent of cases. The peak age incidence of sarcoidosis is in the 20s and 30s,

Approximately 50% of patients are younger than age 30, and about 75% are younger than age 40.

A second peak is noted in middle age women particularly evident in Sweden and Japan.

Women are more likely to have eye and neurologic involvement, erythema nodosum and to be over 40 years.

Men are more likely to be hypercalcemic to have skin involvement (other than erythema nodosum) liver, bone marrow, and extrathoracic lymph node involvement.

Age of onset is of prognostic significance. Sarcoidosis is more likety to evolve into a chronic systemic disease when it occurs in patients older then 40 years.

Etiologic Agent

Sarcoidosis should be viewed as a disease in which both host and environmental factors contribute to the phenotype. The cause of sarcoidosis is not known but it is thought to have an immunological origin. An environmental antigen has been implicated because the disease seems to sometimes present with a “cluster” distribution, affecting focal pockets of a population within a region, or affecting members of a given occupation (firefighters nurses). Whether this antigen is an infectious agent or an environmental antigen as the causative agent is not known.

Environmental agents that have been suggested include beryllium (clinical and histological presentation are very similar to sarcoidosis), organic antigens e.g., pine pollen, peanut dust, and inorganic dusts. It is thought by some that sarcoidosis may be an aberrant response of the host to bacterial infection and organisms that have been implicated include tuberculous and non tuberculous mycobacteria, as well L form of mycobacteria which have deficient cell walls.

Spirochetes, herpes type b, and the agent associated with Whipple’s disease, have also been incriminated.

Pathogenesis

The antigen is thought to act as a hapten that binds to peptides or alters the histocompatibility of complex molecules resulting in the aberrant and destructive immunological response to the patients own tissues.

The aberrant response to the antigen is thought to be a proliferation of the CD-4 lymphocytes (TH1 type) resulting in the production of interleukins IL 1,2,8,10,12,15,18 and especially IL 2 and 18 and tumor necrosis factor alpha. The interleukins in turn cause further expansion of the CD4 cells, which produce cytokines, resulting in progressive acceleration of the inflammatory response.

ANTIGEN DESTRUCTION neutrophils eosinophils macrophages cytotoxic lymphocytes terminal complement components reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates.

A granuloma is an aggregation of macrophages having an enlarged squamous like appearance (epitheloid macrophages) assuming a nodular configuration, and surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes. The acute component of granulomatous cellular disease is not as severe as it might be with a pneumococcal infection for example and so the resulting clinical manifestation is relatively blunted. Systemically this may translate into fever malaise anorexia and weight loss. Depending on the location of the illness, (most commonly in the lungs) it may cause irritation (cough), or loss of function – dyspnea for example.

|

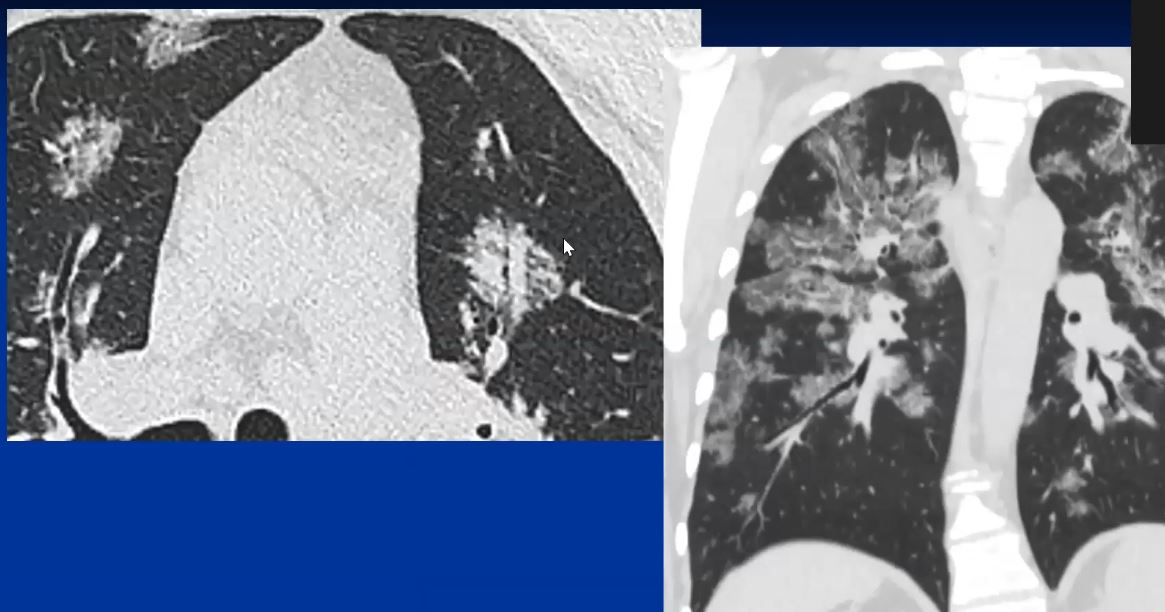

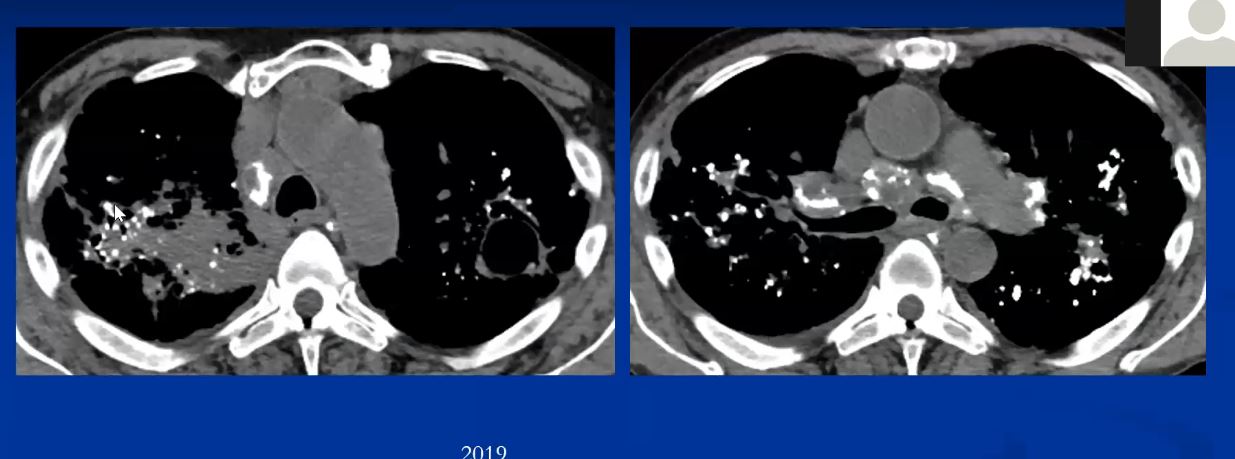

This is a case of cystic sarcoidosis in a 82 year old female who has been followed with mild progression over 7 years. Courtesy David Lee MD.

The granulomas cause structural distortion and as a result associated functional disorder. They may resolve completely or proceed to fibrosis. It thus occupies space and replaces normal functioning tissue. It may also cause irritation and a cough as a result, or if extensive may als cause dyspnea. The clinical presentation ranges from asymptomatic disease to progressive multisystem debilitation. Fever, weight loss, and arthralgias may occur initially. Skin lesions are common. Peripheral lymphadenopathy is important to identify since the nodes represent easy access for biopsy and histological diagnosis. The alternative is transbronchial biopsy.

Complications

End stage interstitial lung disease with honeycombing and cor pulmonale

|

This is a patient with end stage sarcoidosis with honeycomb lung in the lower portion of the specimen and emphysema in the upper part. Courtesy Yale Rosen MD. 54431 code lung pulmonary inflammation sarcoidosis honeycomb emphysema grosspathology

Narrowing of bronchi may result from granulomatous inflammation of the bronchial wall, extrinsic compression from enlarged hilar nodes, or distortion of major bronchi caused by end-stage interstitial disease.

Bronchostenosis 2-26% not usually severe nor symptomatic

Mycetomas (aspergilloma) may develop in cystic spaces (typically in the upper lobes) in patients with advanced (radiographic stage III or IV) sarcoidosis (1-3%) Usually asymptomatic but can invade blood vessels and cause exsanguinating consequence.

|

This is a pathological specimen of a patient with end stage cystic changes of sarcoidosis complicated by a mycetoma. The aspergilloma is in the superior segment of the lower lobe which also shows granulomatous thickening around the bronchovascular bundles. The upper lobe shows multiple cystic changes probably of bronchiectatic origin. 54426 Courtesy Dr Yale Rosen MD UMDNJ

Bronchiectasis – traction

|

This is a pathological specimen from a patient with traction bronchiectasis complicating long standing sarcoidosis. This particular specimen demonstrates sub-pleural saccular bronchiectasis. Courtesy Yale Rosen MD 54433

Natural History

In the majority of cases, the disease will regress spontaneously. Symptoms of sarcoidosis wax and wane spontaneously or in response to treatment.

A high percentage of patients may have complete remission of the symptoms or the radiological findings spontaneously.

Death from sarcoidosis, though rare can happen. It is usually secondary to respiratory failure, neurological complications or cardiac complications.

Age of onset is of prognostic significance. Sarcoidosis is more likety to evolve into a chronic systemic disease when it occurs in patients older then 40 years.

Other negative prognostic indicators include lupus pernio (a chronic rash consisting of papules and plaques usually found on the face), nasal mucosal involvement, chronic uveitis, hypercalcemia, nephrocalcinosis, progressive pulmonary function decline, cystic bone lesions, neurosarcoidosis, and cardiac involvement.

Radiological findings can predict the outcome as well. Patients with bilateral adenopathy on x-ray at presentation usually do better than those with diffuse parenchymal involvement or fibrosis.

Lofgren syndrome, the acute onset of erythema nodosum or periarticular ankle inflammation together with bilateral hilar or right paratracheal lymphadenopathy, is typically associated with a benign course. The disease remits in more than 90% of these cases.

Gross Pathology

Common involvement sites (affects all organ systems)

Lungs, lymph nodes, liver (90%)

|

This is a grosspathology specimen of a patient with sarcoidosis. Note the bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy as well as right paratracheal adenopathy. Courtesy Yale Rosen M.D. 54427

|

This is a gross pathology specimen of a patient with sarcoidosis. Note the fleshy nature of the lymph nodes – hence the name sarcoid – from Gk. sarx (gen. sarkos) = “flesh.” Courtesy Yale Rosen MD UMDNJ 54429

|

This specimen shows significant pleural and subpleural fibrosis in association with some peribronchovascular fibrosis and scarring. Courtesy Yale Rosen MD. 54441

Spleen (60%)

Skin (30%)

Heart kidney bone marrow eyes (20%)

Parotid gland upper airway pancreas skeletal muscle (5%)

Histopathology

non-caseating epithelioid cell granulomas

The characteristic granuloma found in sarcoidosis is discrete and compact. It is composed of multinucleated giant cells, mononuclear phagocytes, and lymphocytes surrounded by tightly organized fibroblasts, mast cells, and an extracellular matrix. Varying quantities of fibroblasts and collagen in the periphery. Dense bands of fibroblasts, mast cells, collagen, and proteoglycans may encase the granulomata and inducing fibrosis and end-organ destruction.

These granulomas typically do not contain focal areas of necrosis (caseation) and tend to occur in lymph nodes, perivascular sheaths, and connective tissue spaces. Some cases of necrotizing granulomas have been described.

|

Granulomas involving visceral pleura in a patient with sarcoidosis. Courtesy Yale Rosen MD.54451

Clinical Presentation

incidental X-ray findings.

For symptomatic patients, the most common presenting problems include respiratory symptoms (95%) (eg, dry cough, dyspnea, chest pain), skin rashes (16%) (eg, erythema nodosum, papules, nodules, plaques), systemic symptoms (eg, fever, night sweats, fatigue, malaise), ocular symptoms (12%) (eg, pain, visual change), and musculoskeletal symptoms (eg, joint pains, myalgias).

Constitutional symptoms is the presenting symptom in 25% of patients including fever (associated with hepatic granulomas) weight loss fatigue and malaise.

Neurologic and cardiac manifestations are less common but can be life-threatening. Encephalopathy, dementia, seizures, headache, or ataxia may be found in patients with central neurologic sarcoid. Syncope, arrhythmias, or congestive heart failure can occur in patients with significant cardiac sarcoid.

Baughman et al. demonstrated that initial presentation of sarcoidosis is related to sex, race, and age.

Women were more likely to have eye and neurologic involvement, have erythema nodosum , and to be age 40 yr or over whereas men were more likely to be hypercalcemic. Black subjects were more likely to have skin involvement other than erythema nodosum, and eye, liver , bone marrow , and extrathoracic lymph node involvement.

Lab Tests

SERUM TESTS

Serum Angiotensin-converting enzyme (Serum ACE) is increased in 50-80% of patients

The test has a low sensitivity and specificity. It was demonstrated that there is no association between serum angiotensin-converting enzyme levels and disease activity or response to treatment.

For monitoring of sarcoidosis , serum calcium, renal function tests

and liver function tests are usually performed.

BIOPSY

The pathological diagnosis is based on finding noncaseating granulomas

in the skin, a peripheral lymph node, salivary gland, bronchoalveolar lavage, or via a transbronchial or transesophageal lung or node biopsy. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy with transbronchial lung biopsies has a yield of greater than 90%, even in patients with predominantly extrathoracic disease.

SKIN TEST

Sarcoidosis patients typically exhibit cutaneous anergy in response to skin testing.The Kveim test a once popularised skin test should not be considered a standard clinical tool.

PULMONARY FUNCTION TEST

Findings consistent with Interstitial Lung Disease

Imaging

Lymph nodes are symmetric

Lymphatic involvement

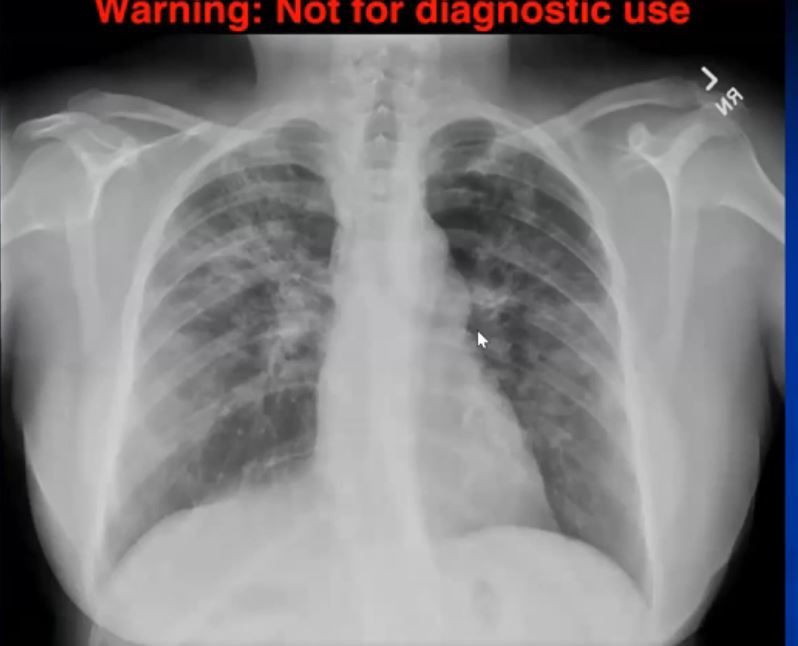

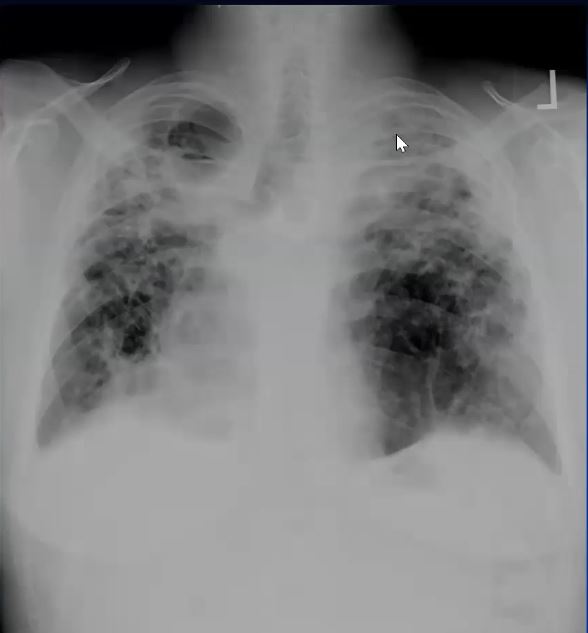

With the non specific nature of the disease and the dilemma associated with its diagnosis together with the high incidence of pulmonary involvement, the most useful diagnostic tool in the disease is the chest x-ray which is abnormal in 90% of cases.

Radiological classification of the disease is based on finding of the CXR.

BASED ON THE CXR (Siltzbach 1967)

Stage 0 – No radiographic abnormality ( 5% )

Stage I – Thoracic lymphadenopathy. Normal lung parenchyma. ( 50% )

Stage II – Hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Abnormal lung parenchyma. ( 30% )

Stage III – Abnormal lung parenchyma. No lymphadenopathy. ( 15% )

Stage IV – Permanent lung fibrosis. ( 20% )

|

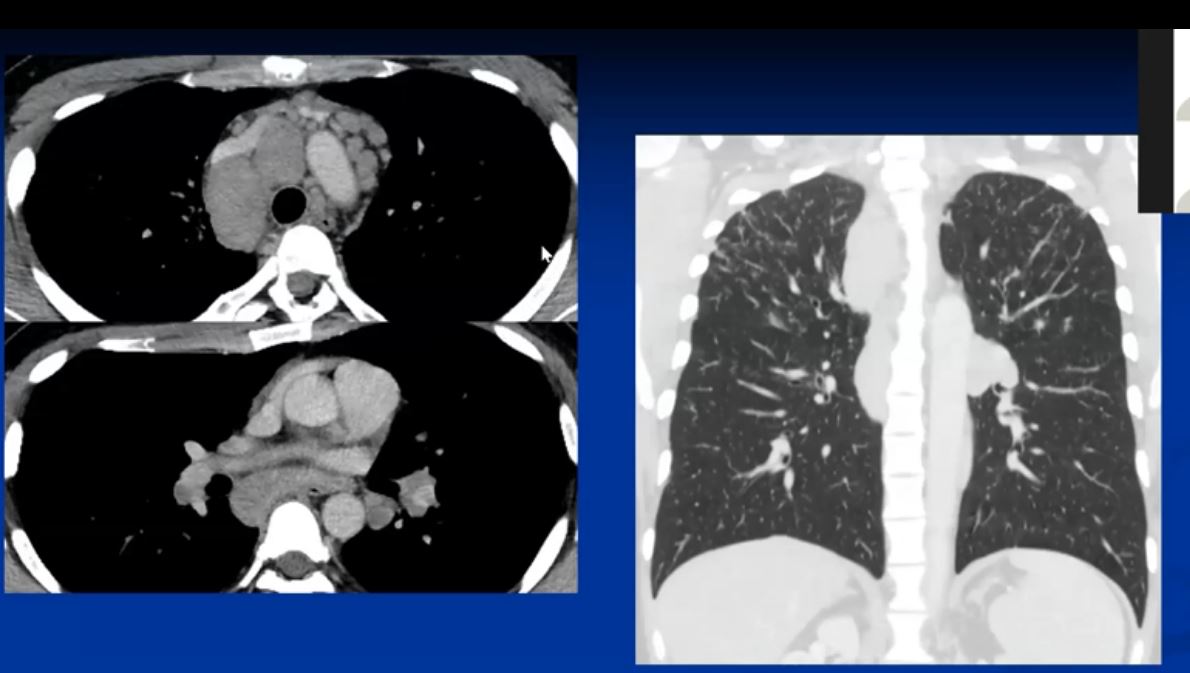

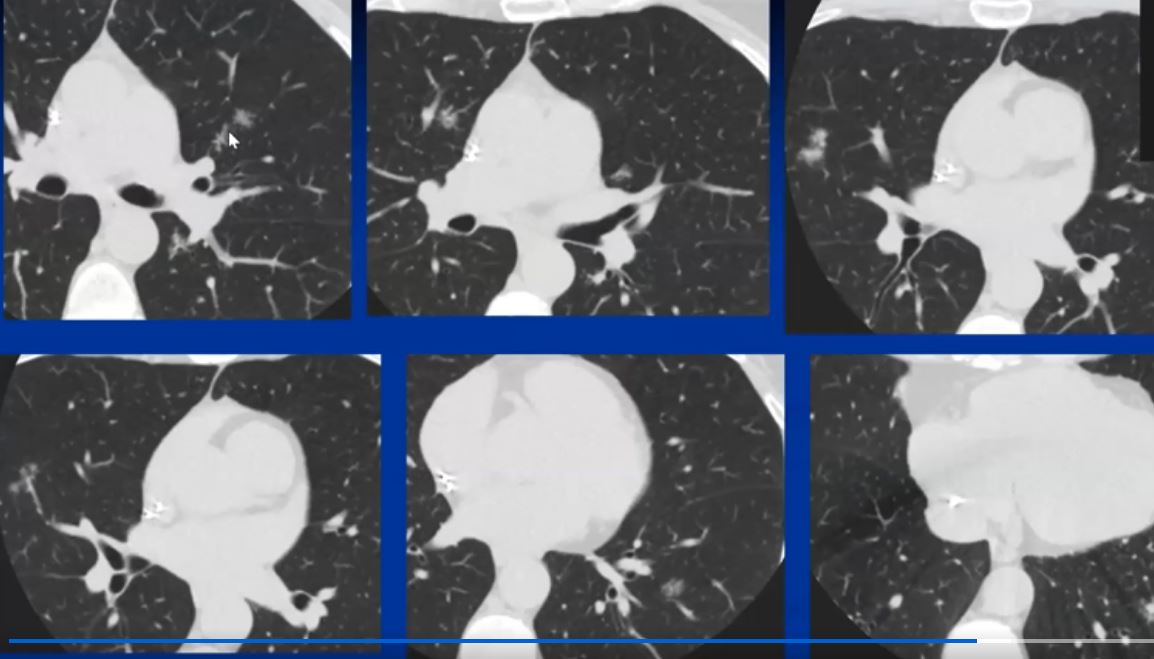

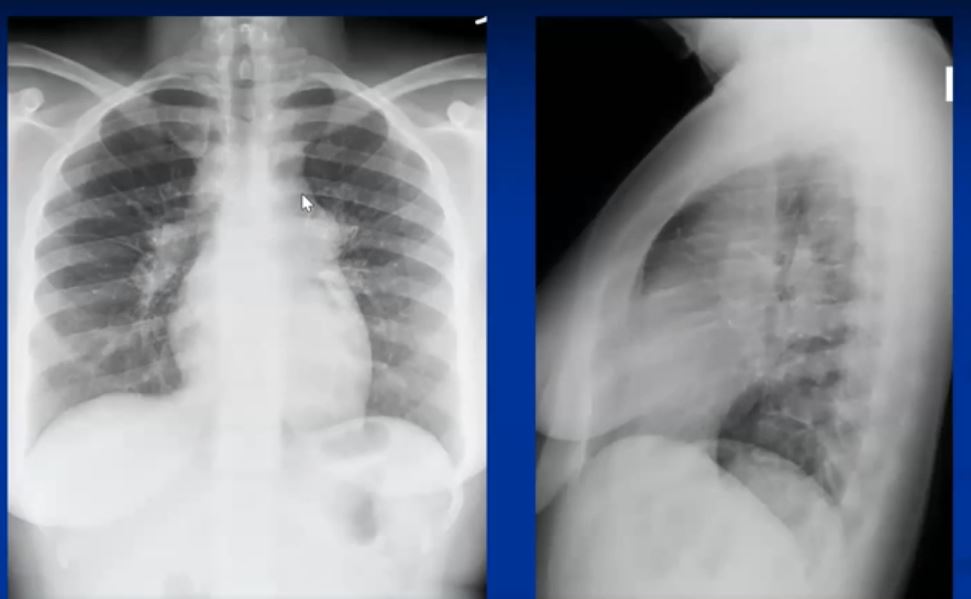

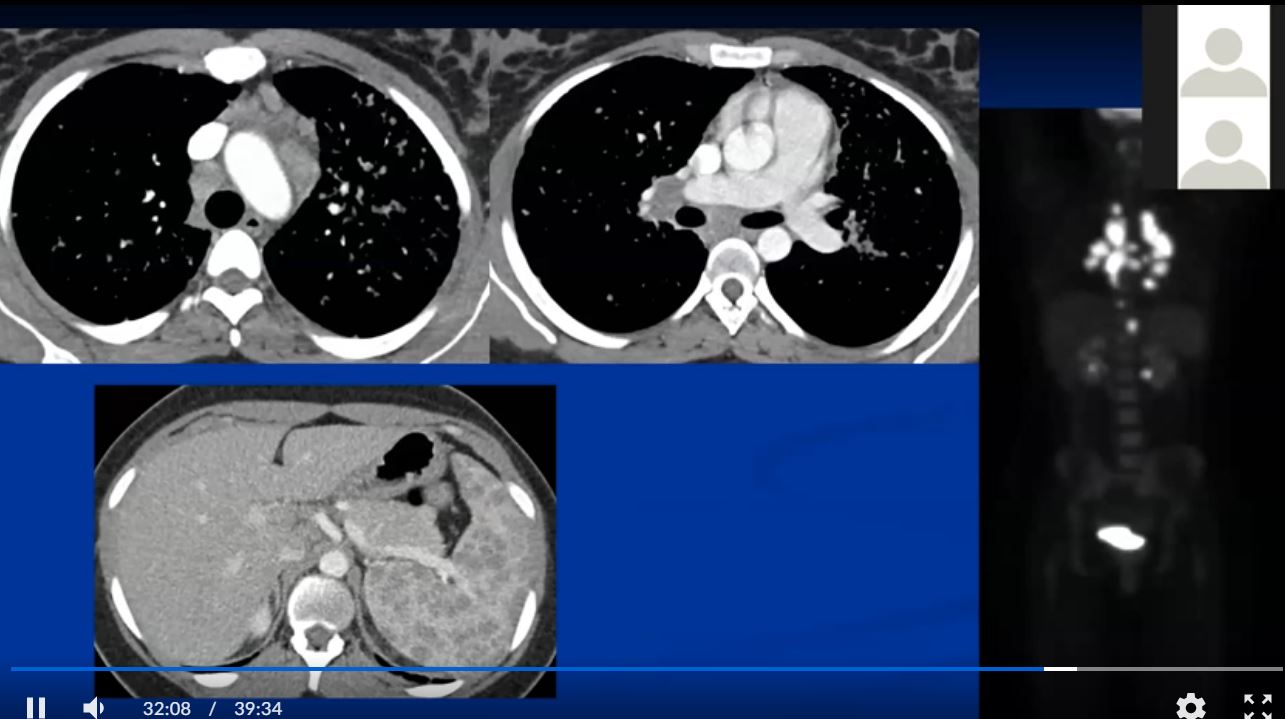

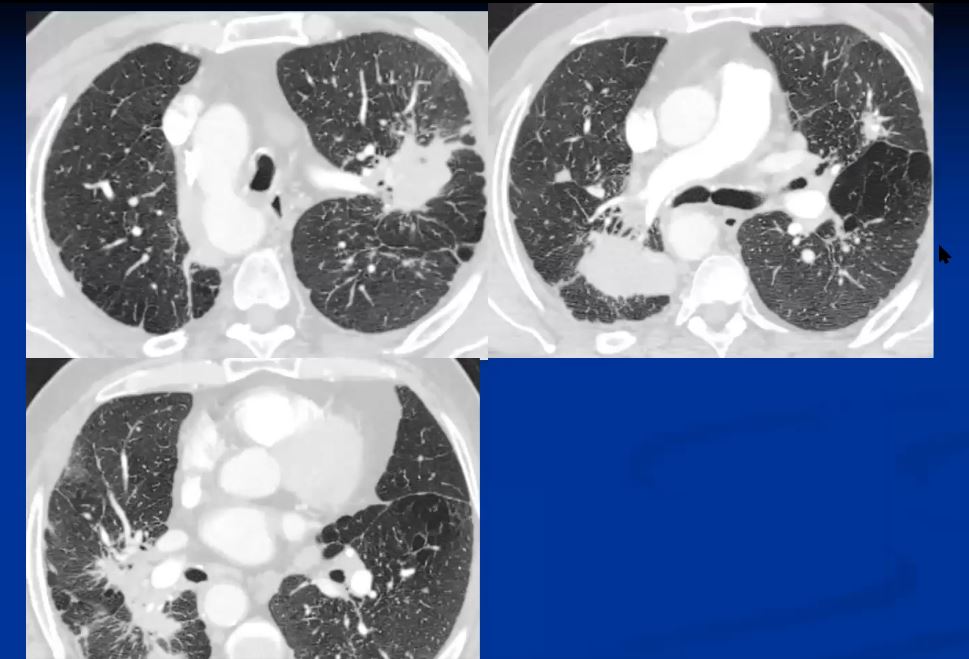

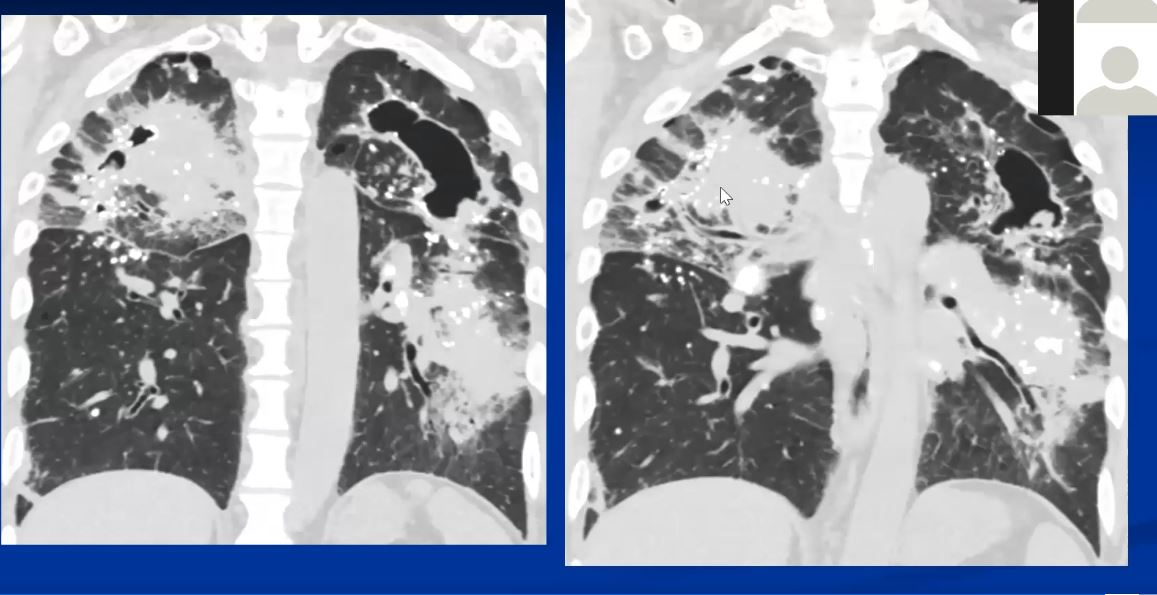

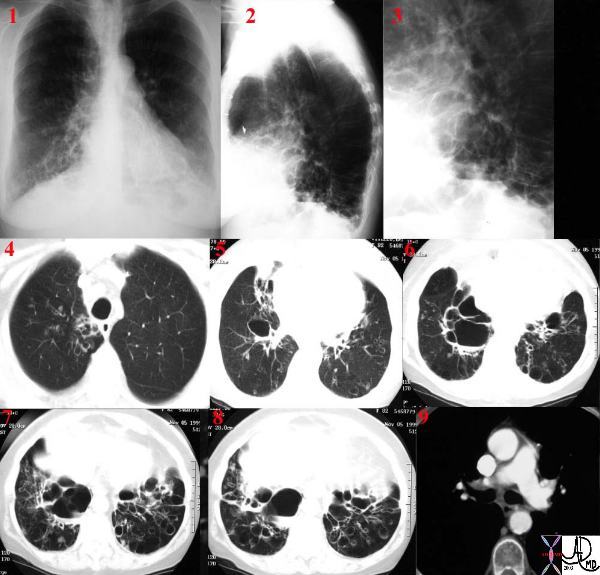

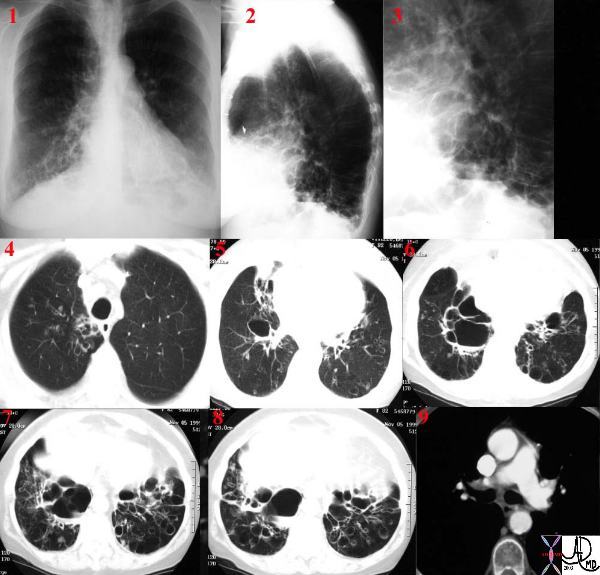

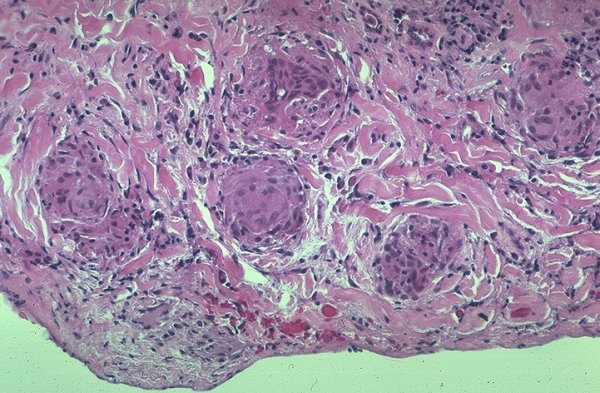

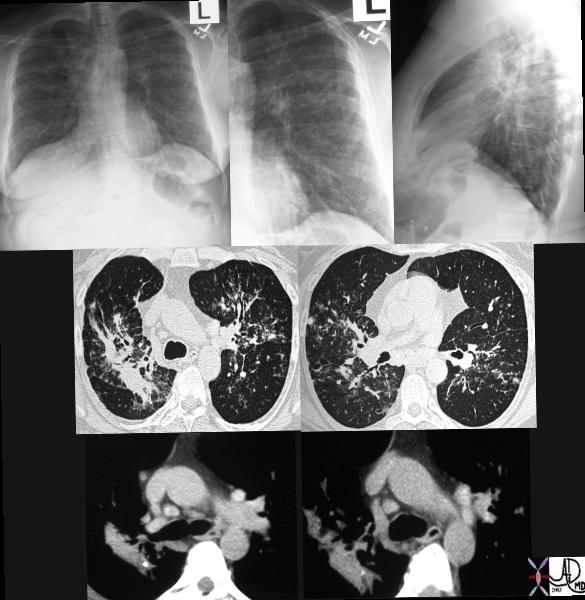

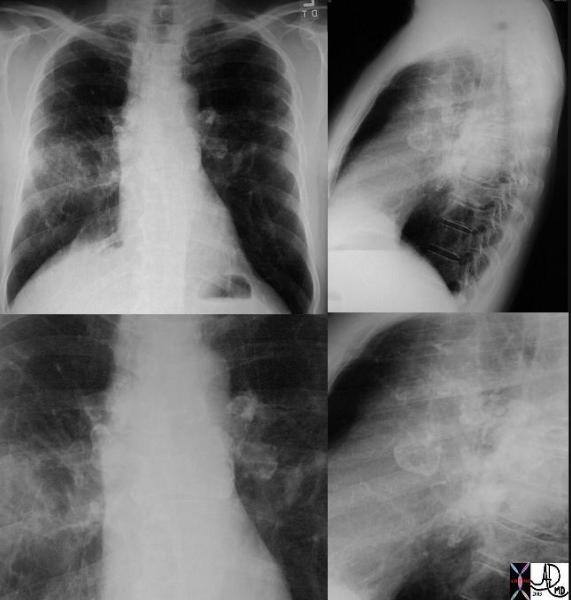

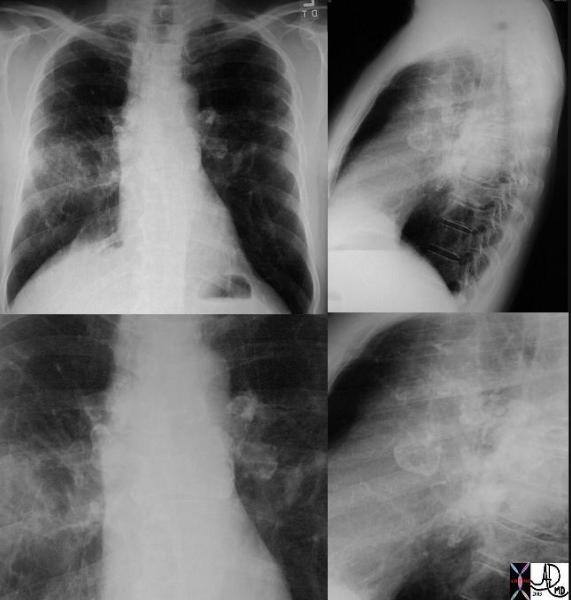

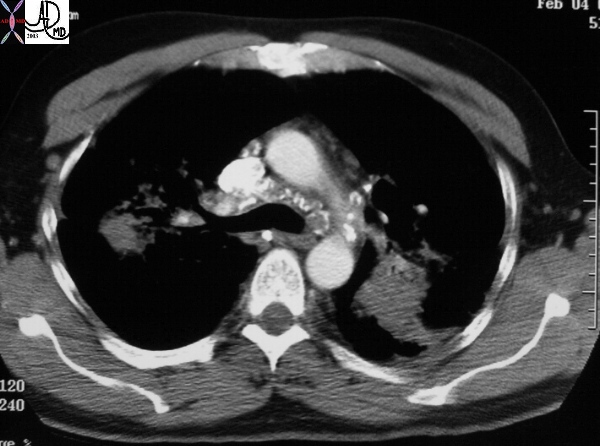

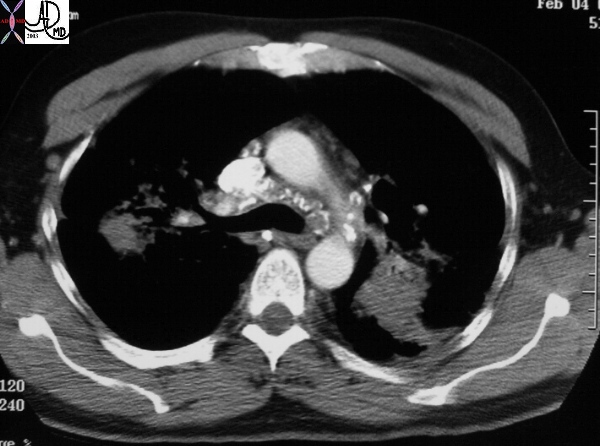

This series of CXRays a CT of a patient with stage III sarcoidosis. She has a son with documented sarcoidosis, and a remote history of erythema nodosum. The CXR (1,2,3) is characterised by upper lobe linear nodular interstitial change, while the CT shows confluent fibrosis, nodules in the parenchyma, along the pleura and major fissure. (4) Image 5 shows nodularity in right and left bronchi. Image 6 shows an intraparenchymal calcified node, while early calcification of mediastinal nodes are noted on image 7. Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD. 31997c

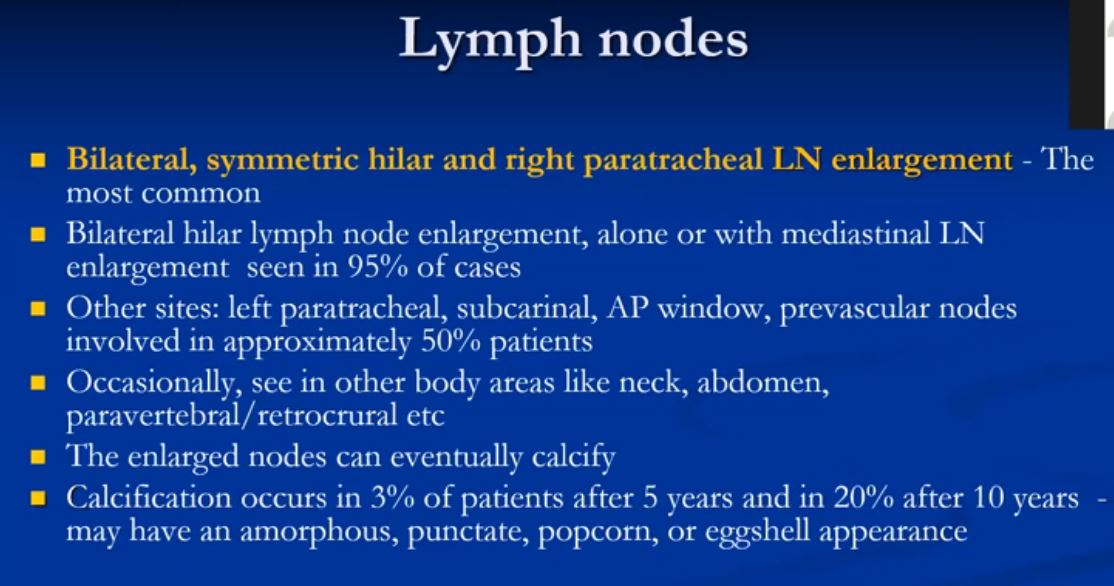

LYMPH NODE DISEASE

The most common radiological features include enlarged hilar and paratracheal lymph nodes, (more specifically right paratracheal node), central bronchovascular and interlobular septal thickening, subpleural and bronchovascular nodular opacities, micronodules, and ground-glass attenuation.

In most patients lymphadenopathy resolves spontaneously. The nodes however may remain enlarged for years, or less commonly stage I patients may resolve and then recur at a later time. Lymph nodes do not progress in size in the patients who present with Stage III disease.

Other considerations with bilateral hilar nodal involvement include infection (particularly fungal or mycobacterial organisms) or malignancy – especially lymphoma. In a patient with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy and normal clinical presentation the chances of sarcoidosis being the causative entity is greater than 95%.

Calcified hilar or mediastinal lymph nodes are noted more often in patients with longstanding sarcoidosis

|

This P-A and lateral examination shows classical egg- shell calcifications of hilar and mediastinal adenopathy, characteristic of silicosis but also seen in sarcoidosis. This is a patient with sarcoidosis. Interstitial disease is also seen in the left lung. Courtesy David Lee MD. 31855c code lungs pulmonary lymph nodes calcified eggshell inflammation sarcoidosis imaging plain film CXR

Sarcoidosis of the Liver with Secondary Cirrhosis and Portal Hypertension |

| 82788.8s 58f sarcoidosis lymph node biopsy proven sarcoidosis of the liver with cirrhosis portal hypertension splenomegaly spleen enlarged left lobe lymph node calcification CTscan Courtesy Ashley DAvidoff MD copyright 2008 |

|

This CT shows classical long standing confluent fibrosis in the upper lobes in this patient with sarcoidosis. The egg-shell calcification of the mediastinal nodes is also classical as is the upper lobe predominance with apical and posterior segmental predominance. Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD 29125/27/28/30/34/35 code eggshell

Asymptomatic patients are more likely to present with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy but can present as well with any of the aforementioned findings.

Symptomatic patients can have only bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy on the X-ray, but are more likely to have parenchymal involvement.

PATTERNS OF THORACIC LYMPHADENOPATHY

Symmetric bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy ( 85% )

Unilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (5% )

Mediastinal lymphadenopathy but no hilar lymphadenopathy ( rare )

Lymph node calcification ( 5% )

Marginal “eggshell” lymph node calcification ( rare )

CALCIFICATION OF THE NODES

The differential diagnosis of calcified mediastinal and hilar adenopathy includes TB.

In general, lymph nodes in sarcoidosis are larger than those in TB (mean diameter 12 mm vs 7 mm). In sarcoidosis the nodes are less likely to be completely calcified 27% vs 62% and more likely to be bilateral bilateral – 65% in sarcoidosis versus 8% in TB. Egg-shell calcification is not a feature of TB, and fairly characteristic but relatively uncommon in sarcoidosis. (9%) (Gawne-Cain)

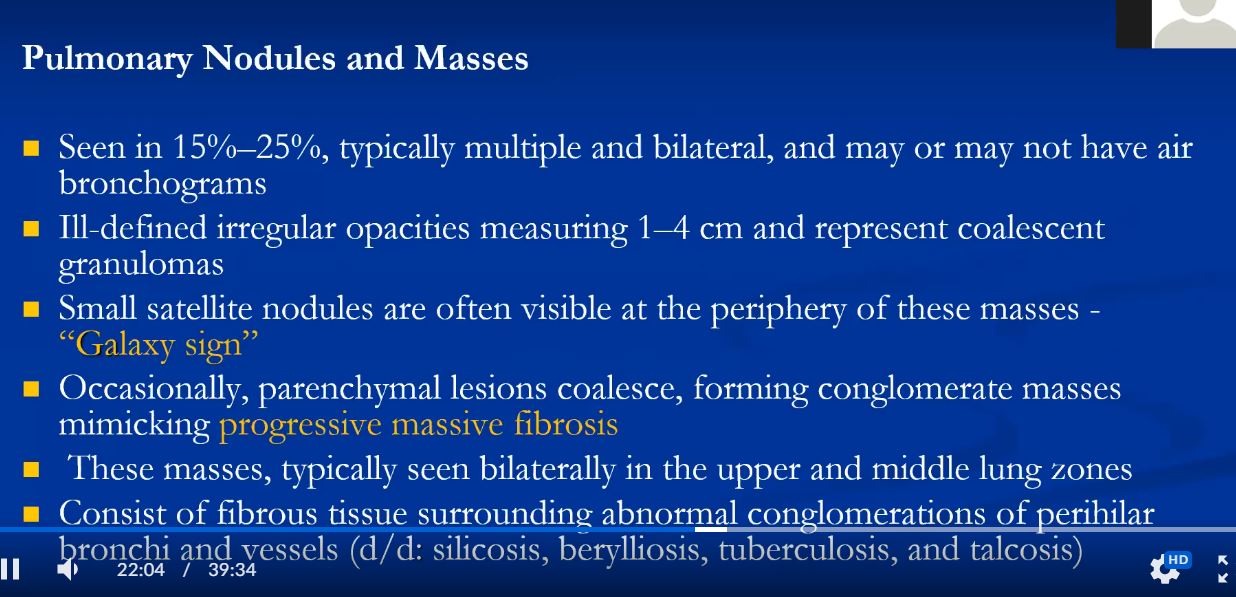

LUNG PARENCHYMAL DISEASE

Lung disease takes the form of a reticular, reticulonodular nodular, or confluent fibrotic pattern manifesting in about 50% of patients. Histologically there is almost always evidence of disease even when the CXR is “normal” Other radiological manifestations include confluent alveolar or nodular opacities with consolidation and air-bronchograms and multiple well-circumscribed pulmonary nodules (“nummular sarcoidosis”) are less common features of sarcoidosis. Rarer radiological patterns include cavitation (2%), and diffuse ground-glass opacities (<1%)

The nodules range in size from 6-10mm.

|

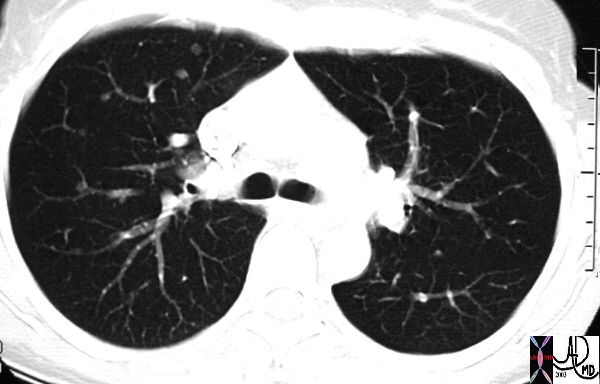

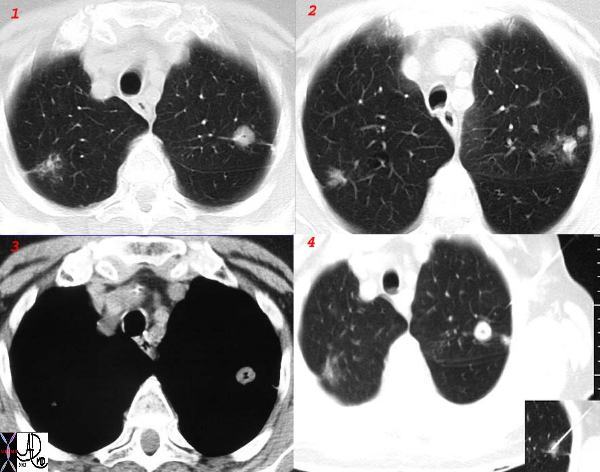

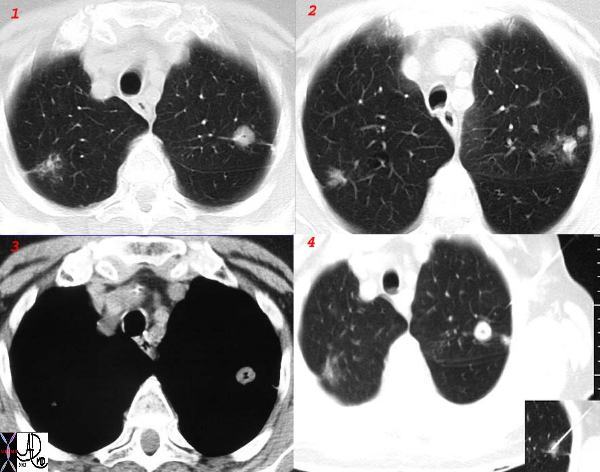

This CT represents the nodular form of sarcoidosis. Note the 5-8mms. nodules in the left upper lobe. Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD.

|

This collage of a cavitating nodule in the left upper lobe in the presence of focally fleeting infiltrates and other lung nodules, in the absence of significant adenopathy proved to be sarcoidosis by biopsy. Cavitating sarcoid is quite unusual but can occur. This nodular form of sarcoid is also called “nummular” sarcoid because of the coin shaped appearance of the nodules. Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD. 31638 c l.jpg code chest lung pulmonary fx nodules cavitating cavitation chronic inflammation sarcoidosis imaging radiology CT scan

CT patterns:

reticular (82%)

nodular (80%)

intense opacification (44%)

ground-glass opacities (42%). (Hansell)

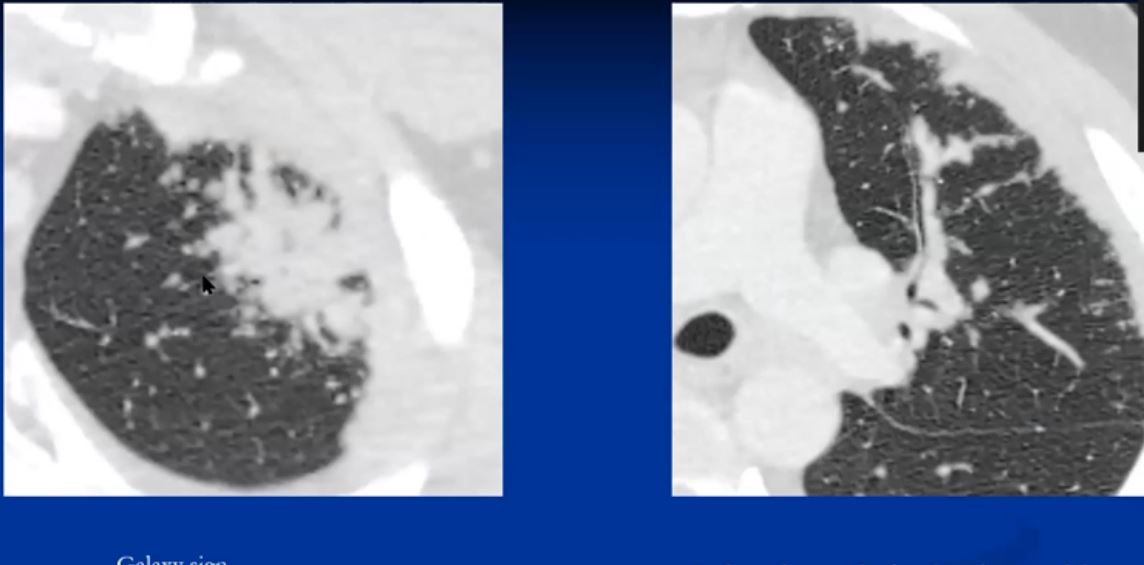

The most characteristic feature of the parenchymal form of sarcoidosis is its association with the lymphatics and pleural and fissural surfaces.

See Case 42 Year Old Man Case

012 Sarcoidosis vs Silicosis in a Cement Worker

Changes also occur along the bronchovascular bundles and in fact on the mucosal surface of the larger airways.

The granulomas are space occupying and may compress small bronchioles resulting in fleeting small focal areas of atelectasis.

Stage IV disease, is most common in the upper lobes and may manifest as linear changes, confluent masses, traction bronchiectasis, volume loss, emphysema, bullae, and honeycomb lung. Symptomatology is mostly independant of the CXR findings, and can range from asymptomatic to significant respiratory difficulty and debilitation. Cor pulmonale can occur. Sarcoidosis and tuberculosis are both common predisposing conditions for mycetoma formation.

|

This collage of CT scans in a patient with sarcoidosis, is characterised by confluent fibrosis, nodules surrounding the bronchovascular bundle of the upper lobes, and pleural nodules. Note in image 2, there are also nodules in the bronchus intermedius and a first subsegmental bronchus probably granulomas. Although lymphadenopathy is present in the hila and mediastinum, they are not particularly large. Note the spiculated nodule in the left lung, simulating carcinoma. Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD. 31826 code chest lung pulmonary confluent fibrosis nodules lymph nodes enlarged chronic inflammation sarcoidosis imaging radiology CTscan

PLEURAL DISEASE

Although the sarcoid nodules seek out the lyphatics of the pleura, pleural effusions are distinctly uncommon (1-4%)

HIGH RESOLUTION CT

This technique has it most useful contribution in discriminating inflammation from fibrosis. The presence of nodules, ground glass or alveolar opacities suggest granulomatous inflammation, which may reverse with therapy while the presence of coarse broad bands, distortion, or traction bronchiectasis, cysts, honeycombing, indicate irreversible fibrosis.

SIZE

The pulmonary nodules range in size from 2-10mm

Lymph nodes in sarcoidosis are larger than those in TB (mean diameter 12 mm vs 7 mm).

SHAPE

The confluent fibrosis often has a axial orientation along the broncho vascular bundles.

The nodules have an irreular shape.

Granulomas along the lymphatics of the secondary lobule may result in a beaded shape of the interlobular septa.

POSITION

There is a predilection for the interstitial lung disease to be central (rather than peripheral) regions and upper lobes (particularly posterior and apical segments) rather than the lower lobes.

Parenchymal infiltrates have an an axial distribution and often emanate from the hila.

The granulomas occur along the lymphatics in the peribronchovascular sheath, and to a lesser extent in the subpleural and interlobular septal lymphatics.

CHARACTER

There may be an air bronchogram in the confluent mass. Calcification in the nodes is not usually complete calcification and may less commonly form a rim – of egg-shell appearance.

Videos

See 22 mins 28secs

References and Links

Criado, E et al Pulmonary Sarcoidosis: Typical and Atypical Manifestations at High-Resolution CT with Pathologic Correlation RadioGraphics Vol. 30, No. 6

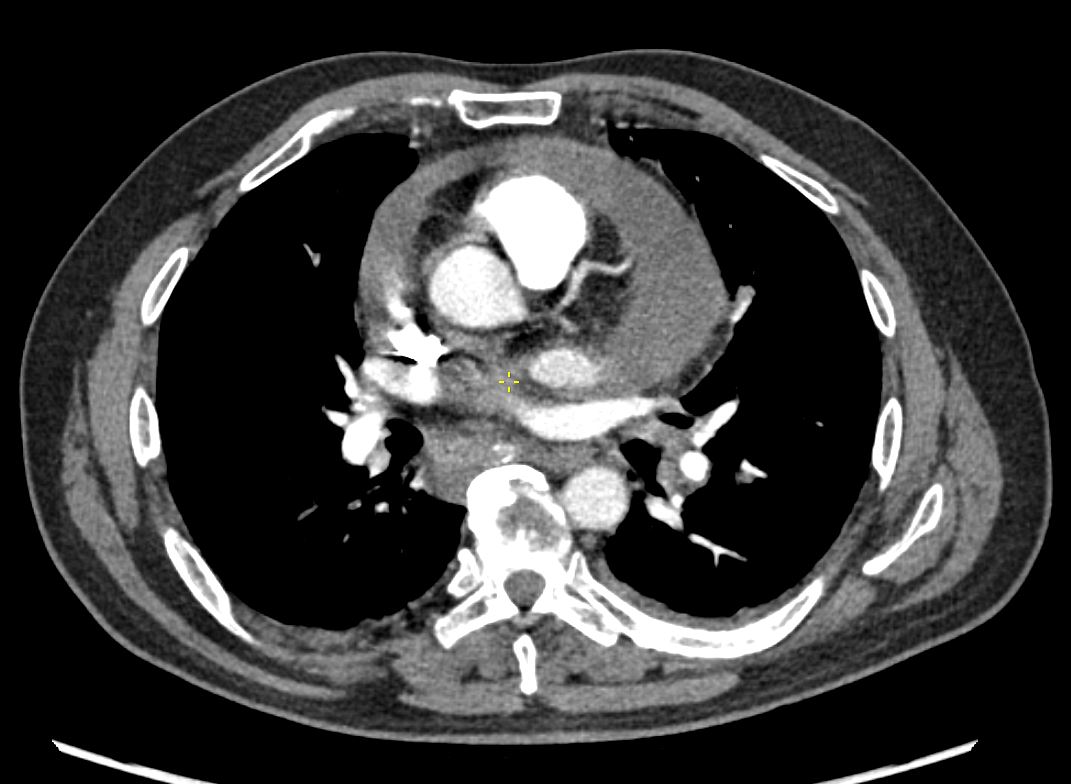

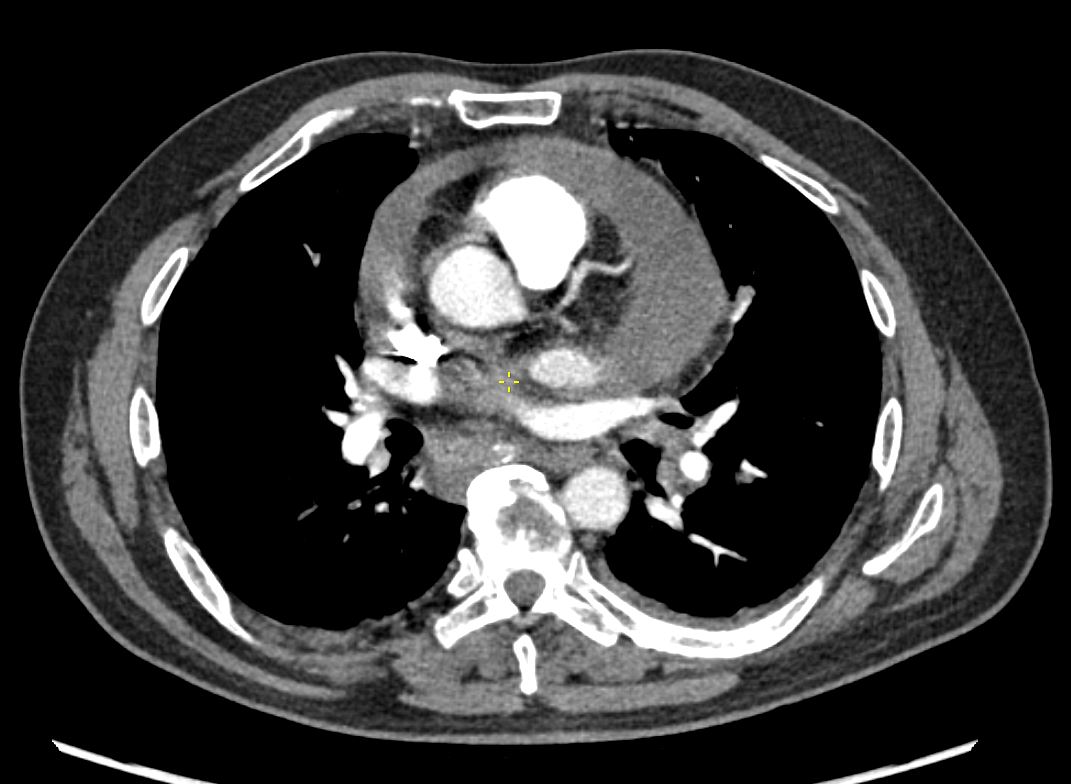

Sarcoidosis and Pericarditis

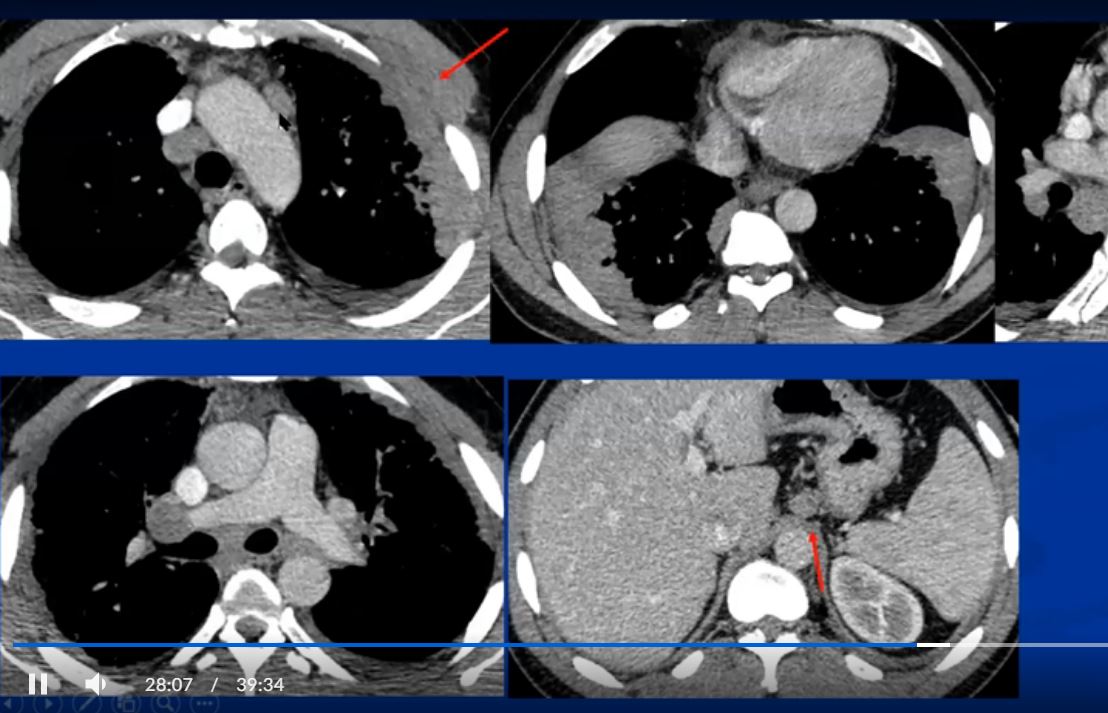

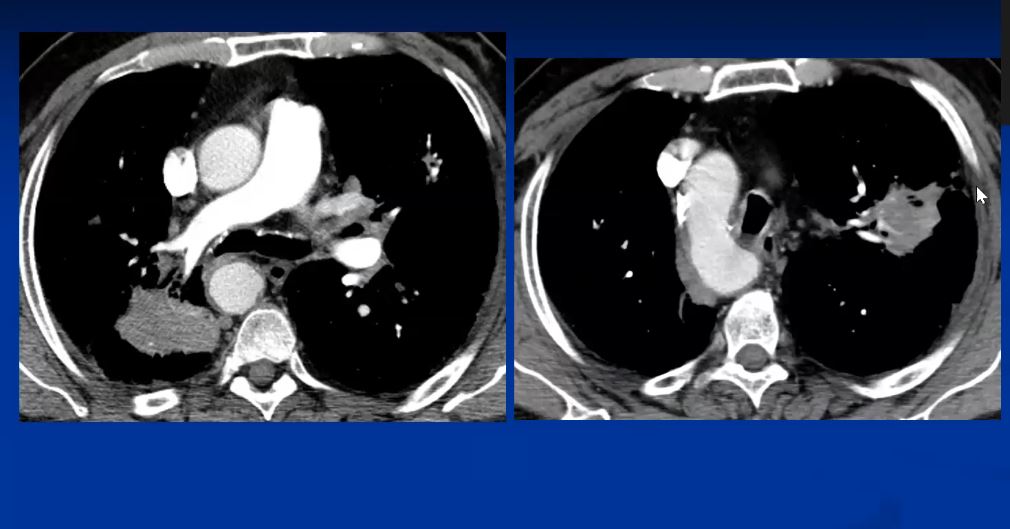

48 year old woman with path proven sarcoidosis of the lung presents with a moderate sized pericardial effusion. There is enhancement of the pericardium anterolaterally characterized by enhancing pericardium. Echo showed no tamponade. She was treated with anti-inflammatory medications and the pericardial effusion resolved . tentative diagnosis of pericarditis secondary to sarcoidosis

Links and References

Criado, E – Radiographics

Hiles Paul Diffuse bronchiectasis as the primary manifestation of endobronchial sarcoidosis