Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

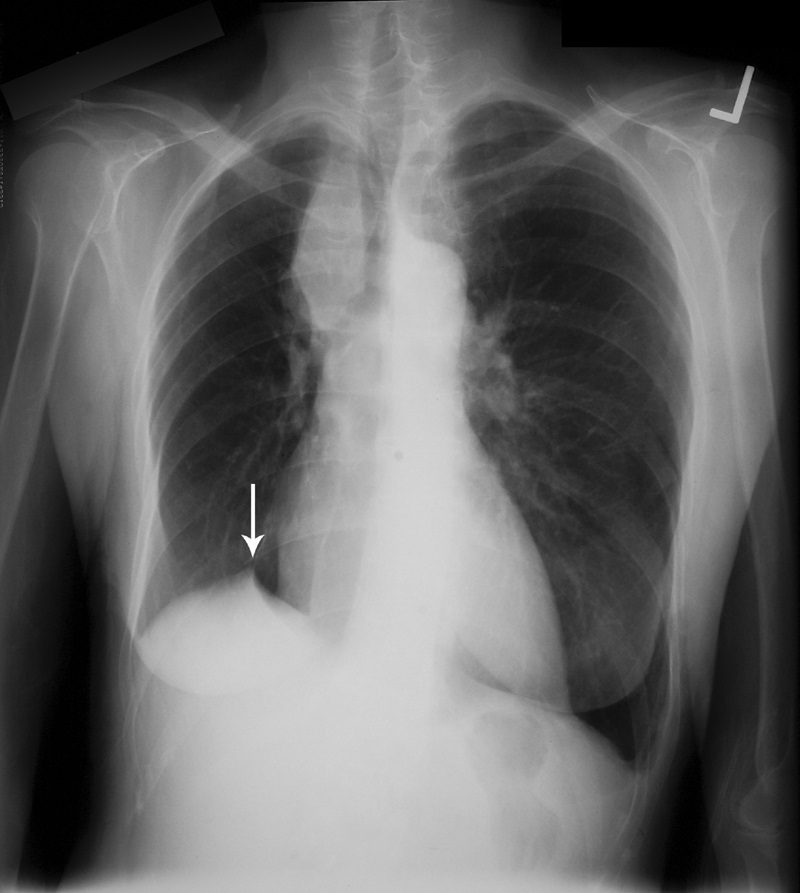

This sign, first documented by Kattan et al in 1980,49 is an ancillary sign of upper lobe collapse, depicted as a triangular opacity projecting superiorly over the medial half of the diaphragm, at or near its highest point (Fig. 16). It is most commonly related to the presence of an inferior accessory fissure.49,50 Although the mechanism is not certain, one theory suggests it is due to the negative pressure of upper lobe atelectasis causing upward retraction of the visceral pleura and extrapleural fat protruding into the recess of the fissure.49 A recent retrospective analysis of patients who have undergone upper lobectomies suggests that the prevalence of the sign increases in the ensuing weeks after intervention and documents its utility in specifically recognizing the type of surgery.51

Doughnut sign

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

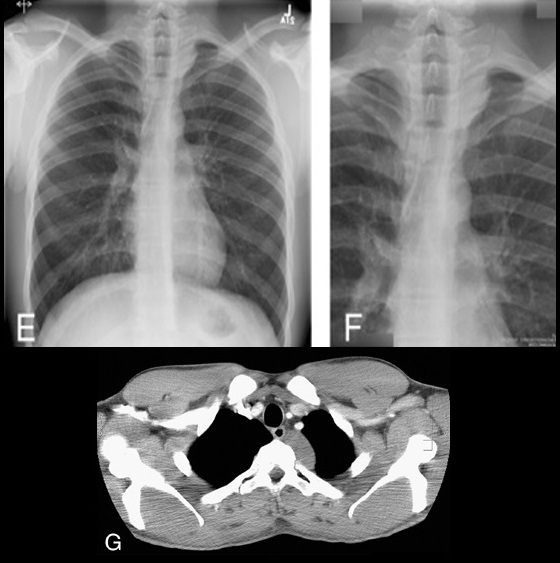

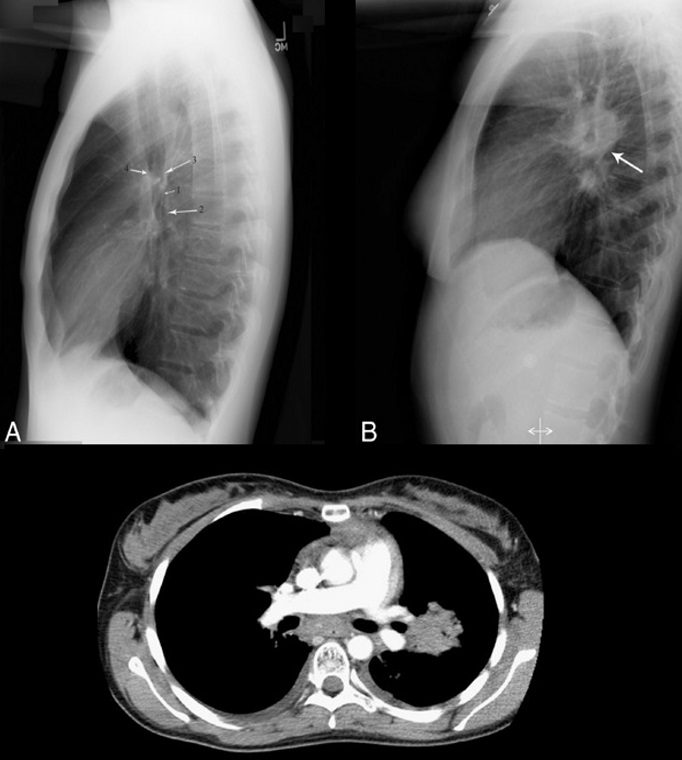

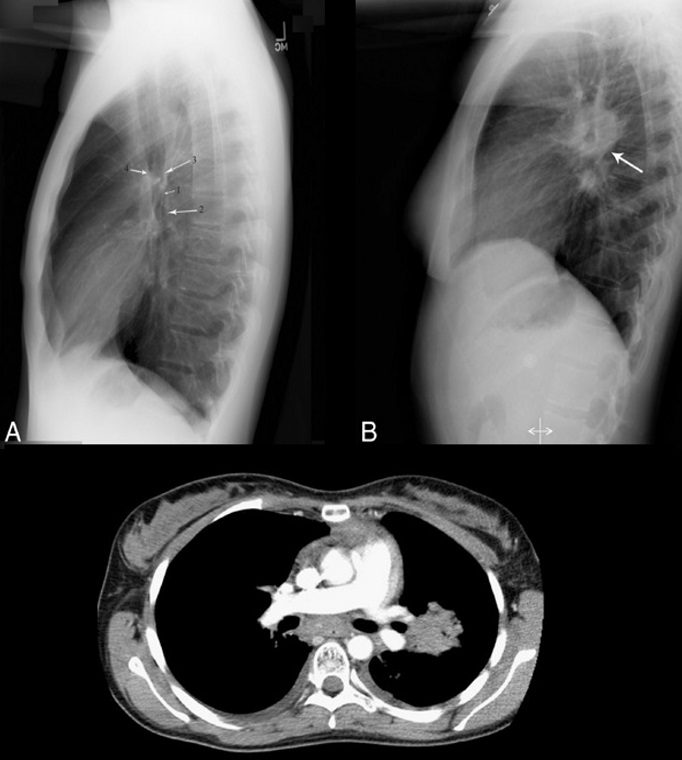

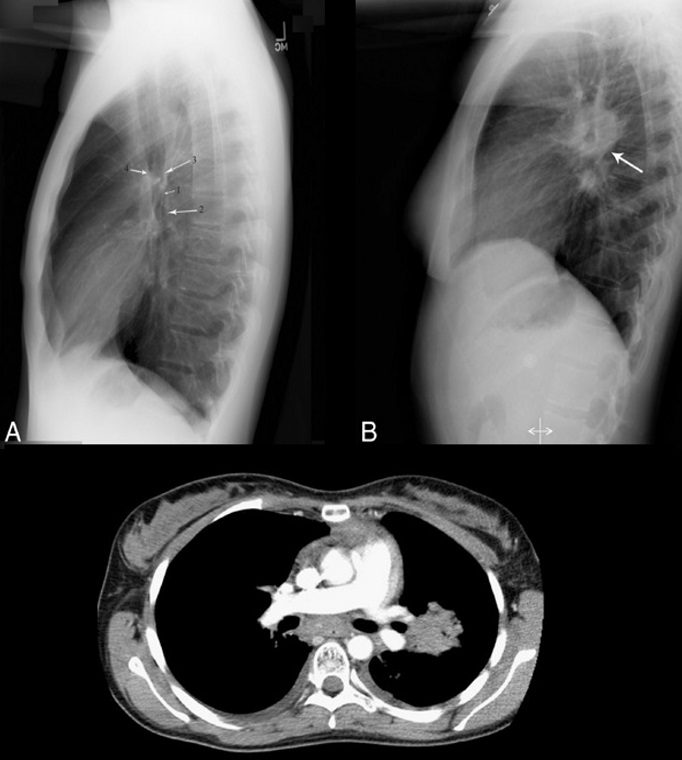

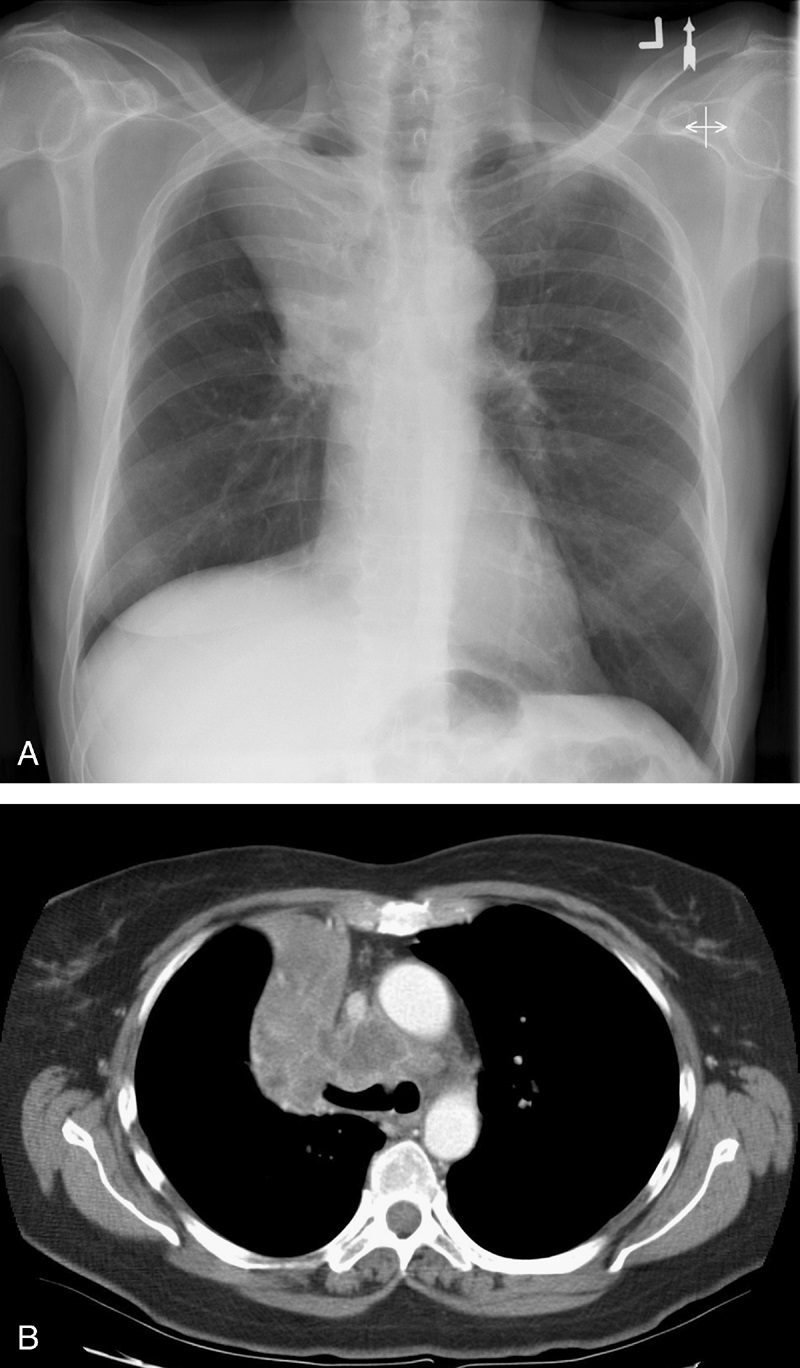

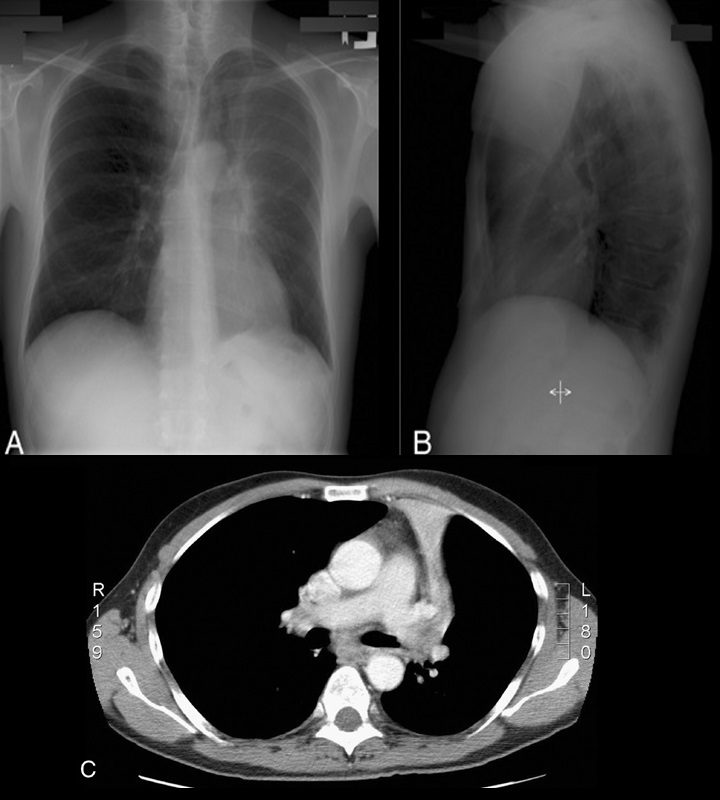

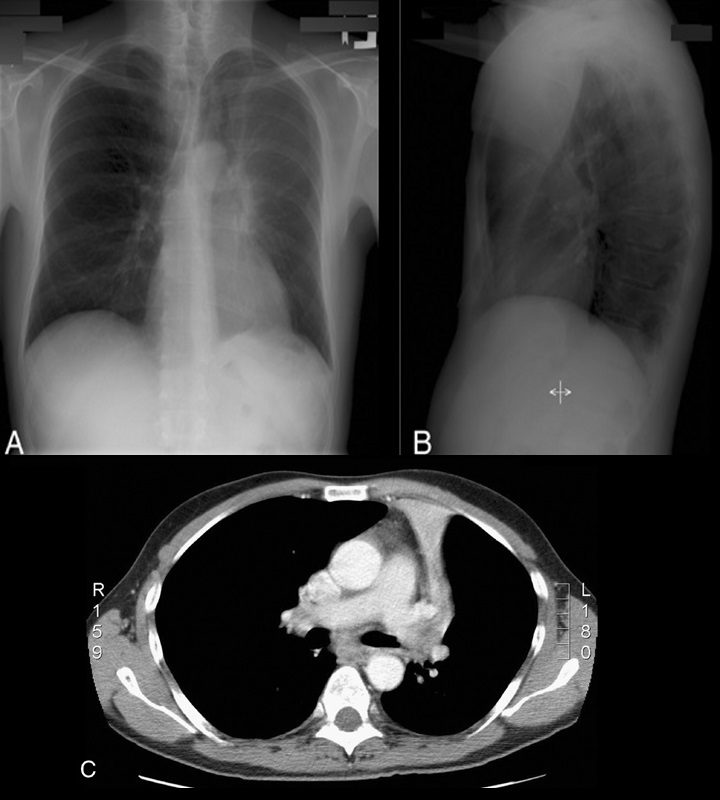

Although CT is widely accepted as the primary modality for detecting mediastinal lymphadenopathy, chest radiography is generally the initial radiographic investigation performed. On a normal lateral chest radiograph (Fig. 10A), the aortic arch and right and left pulmonary arteries are visualized in an “inverted horseshoe” configuration.34 In the presence of subcarinal lymphadenopathy (Figs. 10B, C), the inferior portion of the “horseshoe” fills in.34 The lymphadenopathy appears as a mass posterior to the bronchus intermedius and inferior to the tracheal bifurcation, completing the rounded hilar “doughnut” density.34,35

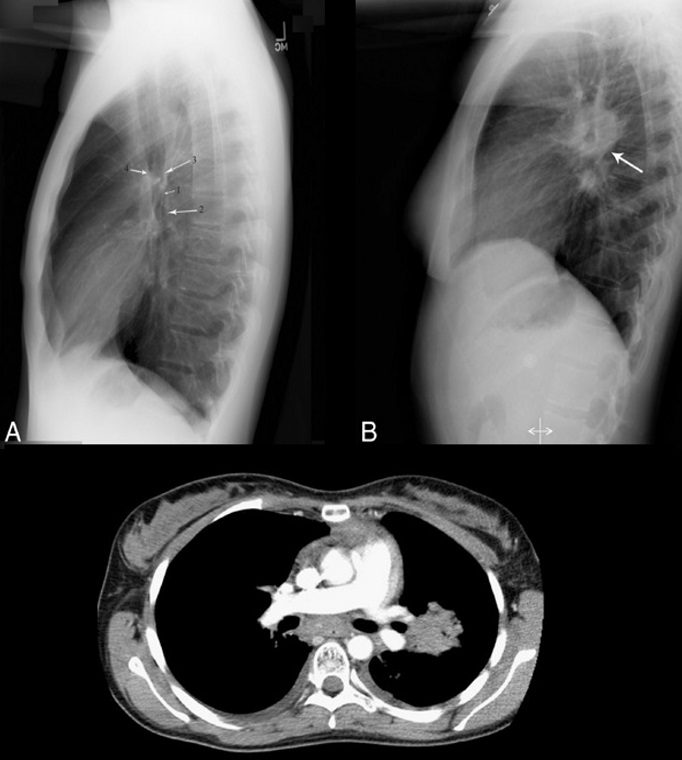

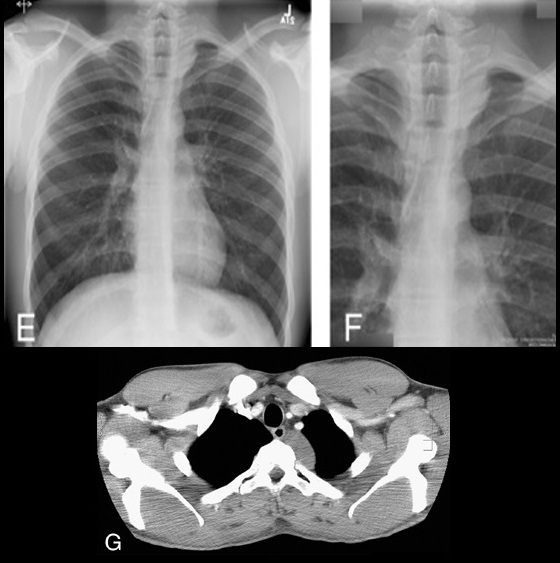

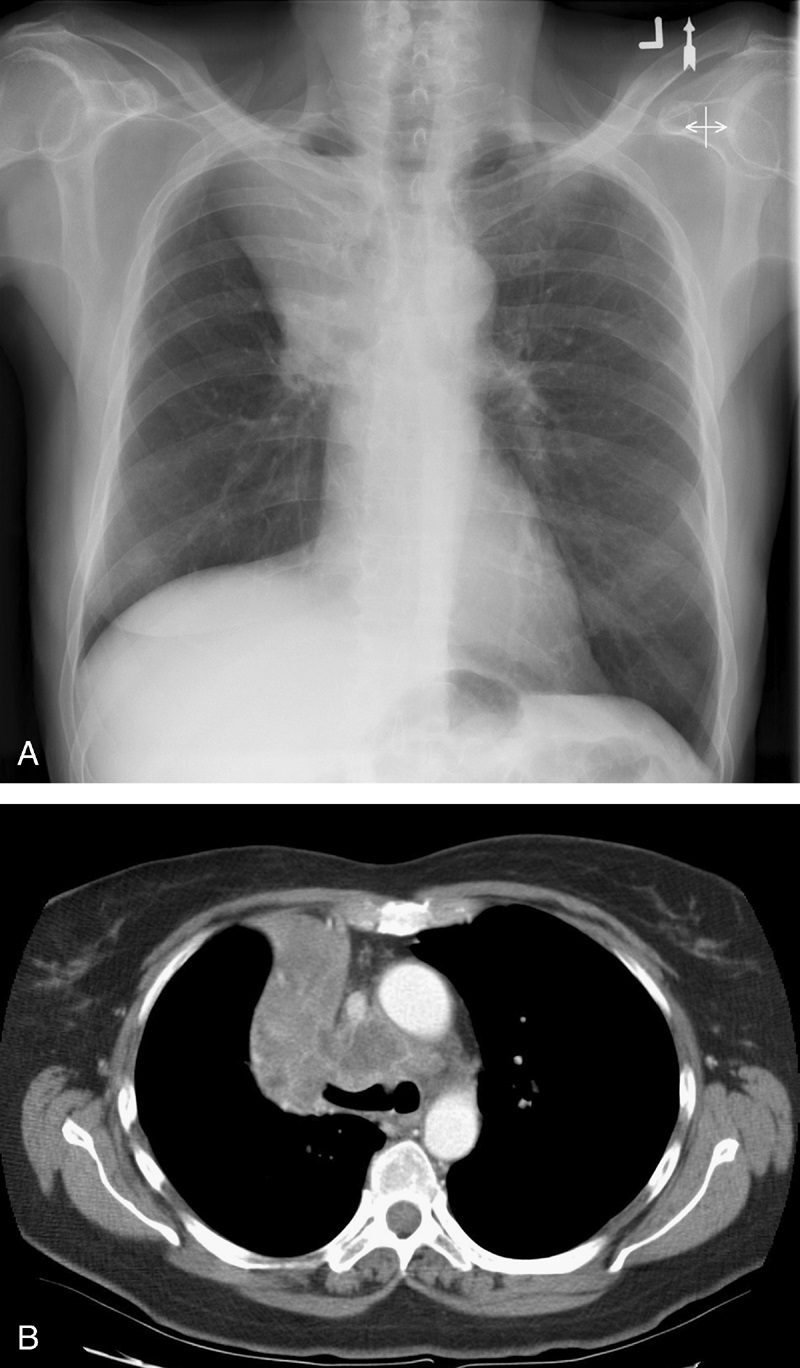

Cervicothoracic sign. Frontal radiograph of the chest with a coned view (A, B) demonstrates a mass projecting over the right superior mediastinum with indistinct borders along its superior margin. Follow-up enhanced CT of the chest (C, D) reveals a mass extending from the cervical region into the anterior mediastinum representing a multinodular goiter. Conversely, in the case of a posterior mediastinal mass, the supralateral margins project above the level of the clavicles and are clearly defined on the frontal radiograph (E, F) in this patient (different patient from A, B) with a biopsy-proven ganglioneuroma (G, CT image).

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

This sign is based on the understanding that if a thoracic mass is in direct contiguity with the soft tissues of the neck, the borders delineating their point of contact will be lost or obscured.11 Anatomically, the thoracic inlet parallels the first ribs, and the posterior aspects of the lung apices extend further superiorly than the anterior portions.12 On PA chest radiographs, a mass clearly delineated on all borders above the level of the clavicles lies posterior to the level of the trachea and completely within the lung.13 When the cephalic border of a mass is obscured at or below the level of the clavicles, it is deemed to be a “cervicothoracic lesion”13 involving the anterior mediastinum (Figs. 3A–E). Mediastinal masses posterior to the trachea are well outlined above the level of the clavicles due to the interface with lung in the posterior aspects of the lung apices (Figs. 3F, G).

Doughnut sign

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

Although CT is widely accepted as the primary modality for detecting mediastinal lymphadenopathy, chest radiography is generally the initial radiographic investigation performed. On a normal lateral chest radiograph (Fig. 10A), the aortic arch and right and left pulmonary arteries are visualized in an “inverted horseshoe” configuration.34 In the presence of subcarinal lymphadenopathy (Figs. 10B, C), the inferior portion of the “horseshoe” fills in.34 The lymphadenopathy appears as a mass posterior to the bronchus intermedius and inferior to the tracheal bifurcation, completing the rounded hilar “doughnut” density.34,35

Golden S sign aka S Sign of Golden

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

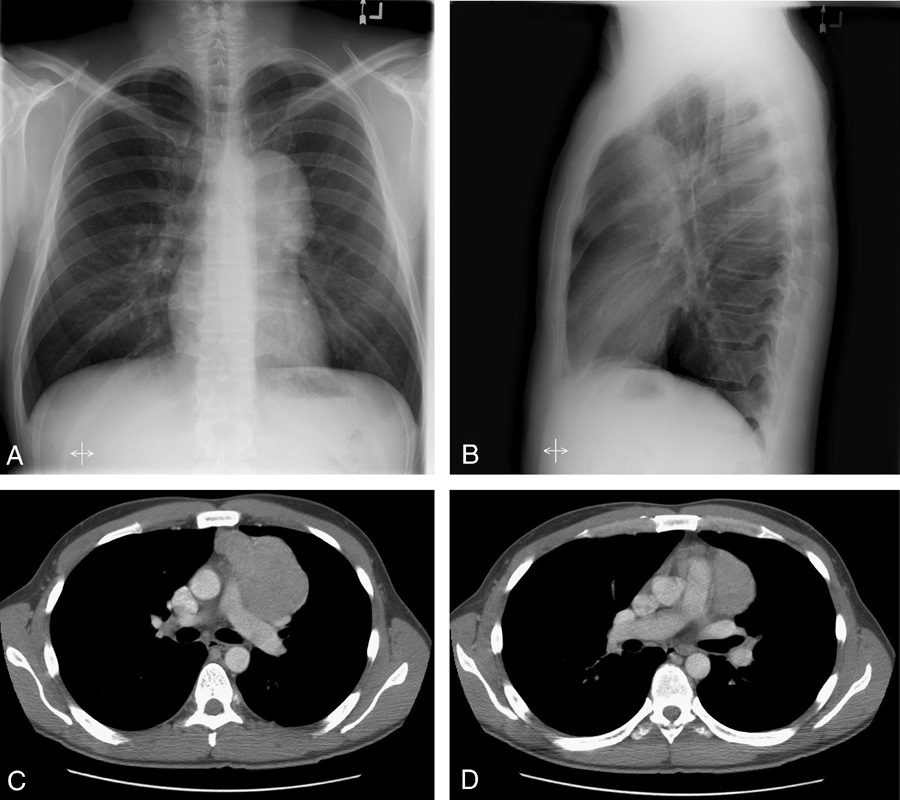

Dr Ross Golden was an American-born radiologist who originally described this sign as a form of right upper lobe collapse associated with a central mass.45 When the right upper lobe bronchus is obstructed by an endobronchial lesion, there is elevation and medial displacement of the minor fissure with proximal convexity of the fissure due to the mass (Fig. 13). This creates the “reverse S” characteristic of central obstructing bronchogenic carcinomas.3,4,45 Given the same presentation of a proximal, obstructing endobronchial lesion within the left upper lobe bronchus with associated left upper lobe collapse, the upwardly retracted major fissure will follow an S-shaped contour along its length. Although initially used to describe signs of right upper lobe collapse, the Golden S sign can be applicable to atelectasis involving any lobe.46

Hilum overlay sign

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

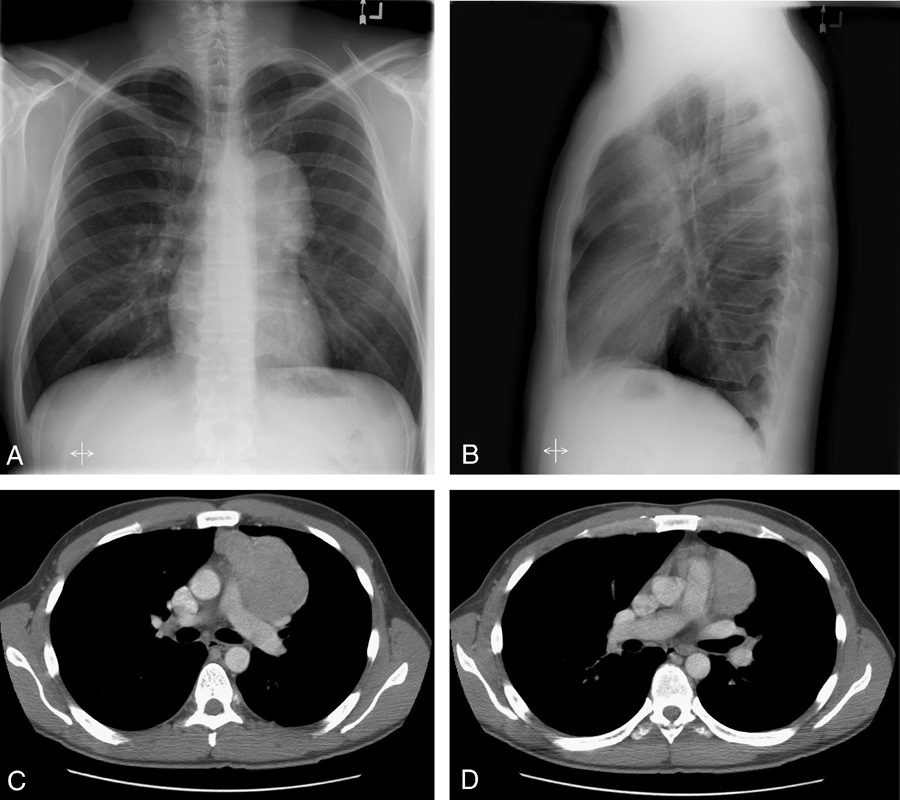

In evaluating densities projecting over the hila on PA chest radiographs, it is important to evaluate whether the opacity blends with the normal hilar shadow of the proximal pulmonary arteries and obscures clear visualization or if the mass and hilar structures are overlapping but distinct from one another. If the hilar vessels are sharply delineated, then it can be assumed that the overlying mass is anterior (Fig. 15) or posterior to the centrally located vascular structures and the intervening aerated lung enables crisp visualization of the pulmonary vessels.12,13 However, when the mass is inseparable from the proximal pulmonary arteries, it is assumed that the structures are immediately adjacent to one another, with the lack of interposing air obscuring the margins of the normal hilar structures. This sign was originally described by Benjamin Felson.12,13

Luftsichel sign

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

The word Luftsichel is German for “air crescent.” The finding is seen in the setting of left upper lobe collapse. Due to the absence of a minor fissure on the left, as the left upper lobe collapses, the major fissure assumes a vertical position roughly parallel to the anterior chest wall.4 As volume loss progresses, the fissure continues to migrate more anteriorly and medially until the atelectatic lobe is contiguous with the left heart border, effectively obliterating its contour on the frontal radiograph (Figs. 17A–C). With movement of the apical upper lobe segment anteromedially, the superior segment of the left lower lobe hyperinflates and fills the vacated apical space.4,52 Occasionally this segment will insinuate itself between the aortic arch and the collapsed left upper lobe creating a sharp outline, or periaortic lucency, described as the Luftsichel.3,4,52