Etymology

Derived from the Latin word infarctus, meaning “stuffed into” or “obstruction,” referring to tissue necrosis caused by vascular occlusion.

AKA

Lung Infarction.

What is it?

Pulmonary infarction is necrosis of lung tissue due to obstruction of the pulmonary vasculature, most commonly by a thromboembolic event. Oxygenation from alveolar air is insufficient to sustain tissue viability when blood supply is severely compromised.

Caused by

- Most common cause:

- Thromboembolism: Pulmonary embolism (PE).

- Less common causes:

- Infection: Septic emboli.

- Inflammation/Immune: Vasculitis (e.g., granulomatosis with polyangiitis).

- Neoplasm: Tumor emboli or compression by a mass.

- Mechanical trauma: Direct injury to the pulmonary vessels.

- Metabolic: Sickle cell crisis.

- Circulatory: Heart failure, hypoperfusion states.

- Inherited: Hypercoagulable states (e.g., Factor V Leiden).

- Congenital: Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations.

Resulting in

- Hypoxia.

- Lung necrosis.

- Hemorrhage in the affected area.

Structural Changes

- Wedge-shaped area of necrosis.

- Peripheral and pleura-based location.

- Hemorrhagic consolidation.

Pathophysiology

- Obstruction of the pulmonary artery → ischemia → tissue necrosis.

- Dual blood supply (pulmonary and bronchial arteries) often protects the lung but fails in cases of significant embolism or compromised bronchial circulation. Alveolar oxygenation can sustain some viability but not enough to prevent infarction during severe ischemia.

Pathology

- Coagulative necrosis of lung parenchyma.

- Hemorrhagic infiltration due to vascular leakage.

Diagnosis

- Clinical features, imaging studies, and labs.

Clinical

- Acute pleuritic chest pain.

- Hemoptysis.

- Dyspnea.

- Fever (sometimes).

Radiology

CXR Findings

- Hampton’s Hump: Peripheral wedge-shaped opacity with the base against the pleural surface, representing infarcted lung tissue.

- Westermark Sign: Focal oligemia distal to the site of embolism (uncommon).

- Fleischner Sign: Enlarged pulmonary artery due to an embolus (uncommon).

- Associated findings: Atelectasis, small pleural effusion, or consolidation.

CTPA Findings

Parts: Segmental or subsegmental regions of lung tissue.

Size: Variable, proportional to the extent of vascular obstruction.

Shape: Wedge or triangular-shaped infarction, apex pointing toward the hilum, and base against the pleural surface.

Position: Typically peripheral and pleura-based.

Character:

- Hemorrhagic necrosis: Hyperdense in acute settings due to hemorrhage.

- Enhancing viable tissue surrounding the infarct.

- Central filling defect in the pulmonary artery representing an embolus.

- Occlusive thrombus: High-density filling defect in the pulmonary artery at the site of vascular obstruction.

- Feeding Vessel Sign: A pulmonary artery leading directly to a lesion, commonly seen in infarctions associated with PE.

Dual-energy CTPA: Demonstrates decreased iodine perfusion in infarcted areas, enhancing diagnostic accuracy and correlation with perfusion abnormalities. It is not recommended for use in pregnancy due to its similar radiation exposure as conventional CTPA.

Associated Findings:

- Pleural effusion.

- Secondary consolidation.

- Bronchial dilatation in adjacent non-necrotic areas.

- Right Ventricular (RV) Strain: May be seen in large PE cases, indicated by bowing of the interventricular septum or RV enlargement.

Other Imaging Modalities

- Ventilation-Perfusion (V/Q) Scan:

- Mismatch pattern: Perfusion defect without a corresponding ventilation defect indicates high probability for PE.

- Sensitivity: Useful in pregnancy and patients with contraindications to CT.

- Doppler Ultrasound: Indicates thrombosis of the deep veins that have the potential to embolize, but it does not directly diagnose PE.

- MRI: Rarely used; beneficial for soft tissue differentiation or in patients with contraindications to ionizing radiation.

- PET-CT: Differentiates malignancy or alternative pathology.

- NM Angiography: Limited role; used as a secondary diagnostic tool.

Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs)

- Typically not diagnostic but may show reduced lung volume or compliance in chronic cases.

Labs

- Elevated D-dimer (sensitive but nonspecific).

- Arterial blood gases: Hypoxemia, respiratory alkalosis.

- Coagulation profile: Identifies hypercoagulable states.

Management

- Medical:

- Anticoagulation therapy: Heparin (acute), warfarin or DOACs (long-term).

- Thrombolysis: Indicated in massive PE or hemodynamic instability.

- Supportive:

- Oxygen therapy.

- Pain management with NSAIDs or opioids.

- Surgical/Interventional:

- Embolectomy (rare, severe cases).

- IVC filter for recurrent embolism or anticoagulation contraindications.

Pregnancy Considerations

- Doppler DVT, if positive, is helpful since treatment can be initiated.

- If Doppler negative, V/Q scan over CTPA is preferred to minimize radiation exposure.

- Anticoagulation with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is the first-line therapy.

Recommendations

- Prompt recognition of symptoms and early imaging.

- Anticoagulation as a first-line treatment.

- Regular follow-ups in patients with recurrent embolism risk.

Key Points and Pearls

- Pulmonary infarction is uncommon due to dual lung blood supply and alveolar oxygenation; consider large emboli or bronchial circulation compromise when present.

- Radiologic signs such as Hampton’s Hump, Westermark Sign, Fleischner Sign, and Feeding Vessel Sign are key diagnostic markers.

- When CTPA is contraindicated such as pregnancy or severe allergy to iodinated contrast, Doppler DVT, if positive, is helpful since treatment can be initiated. V/Q scans may be used in high-risk cases if Doppler is negative.

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

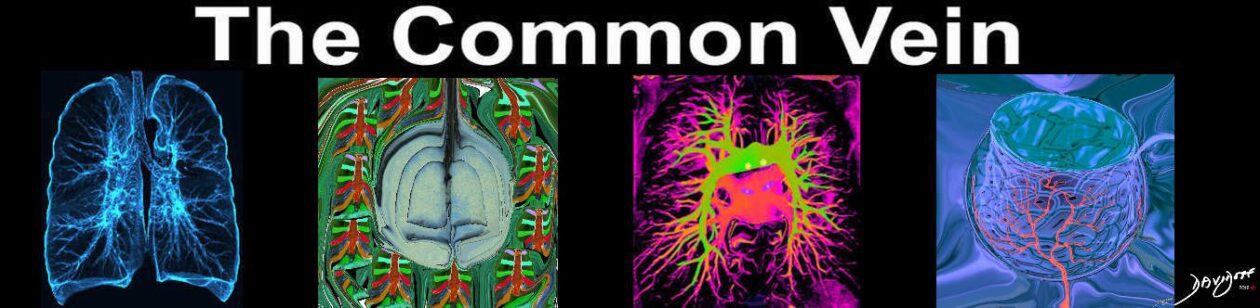

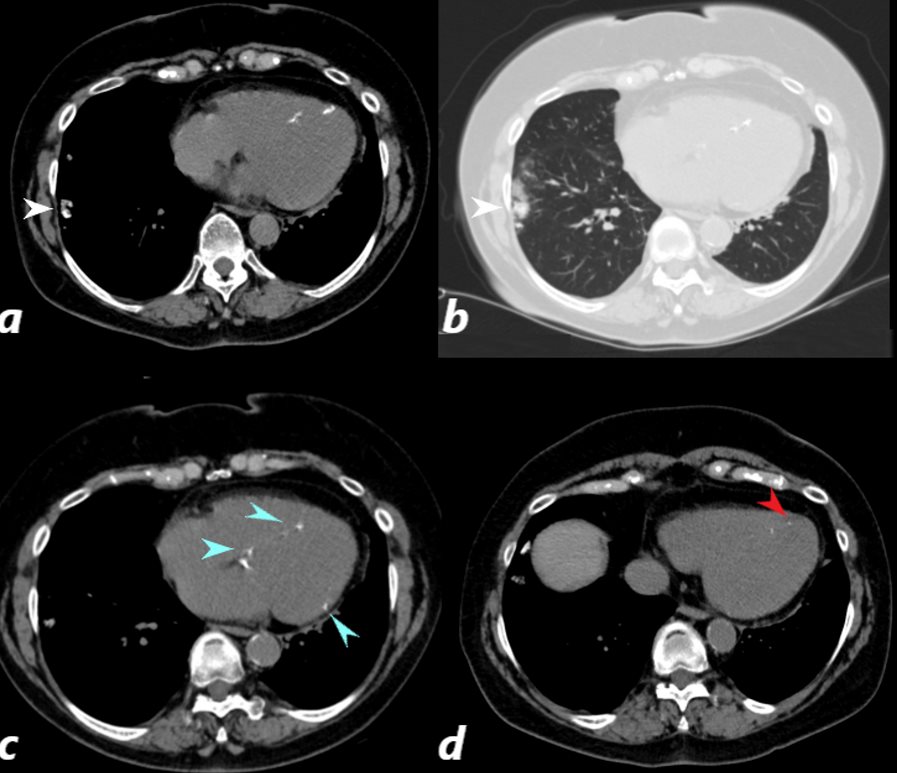

40 year old male with SLE presented with chest pain and dyspnea and initial CXR showed a vague retrocardiac density

A CT scan reconstructed in the oblique projection shows occlusive pulmonary emboli to the left lower lobe (white arrowhead,a) associated with a wedge shaped infarct (red arrowhead a,b)

Ashley Davidoff MD

key words

CT scan

SLE

PE

pulmonary embolism

pulmonary infarct

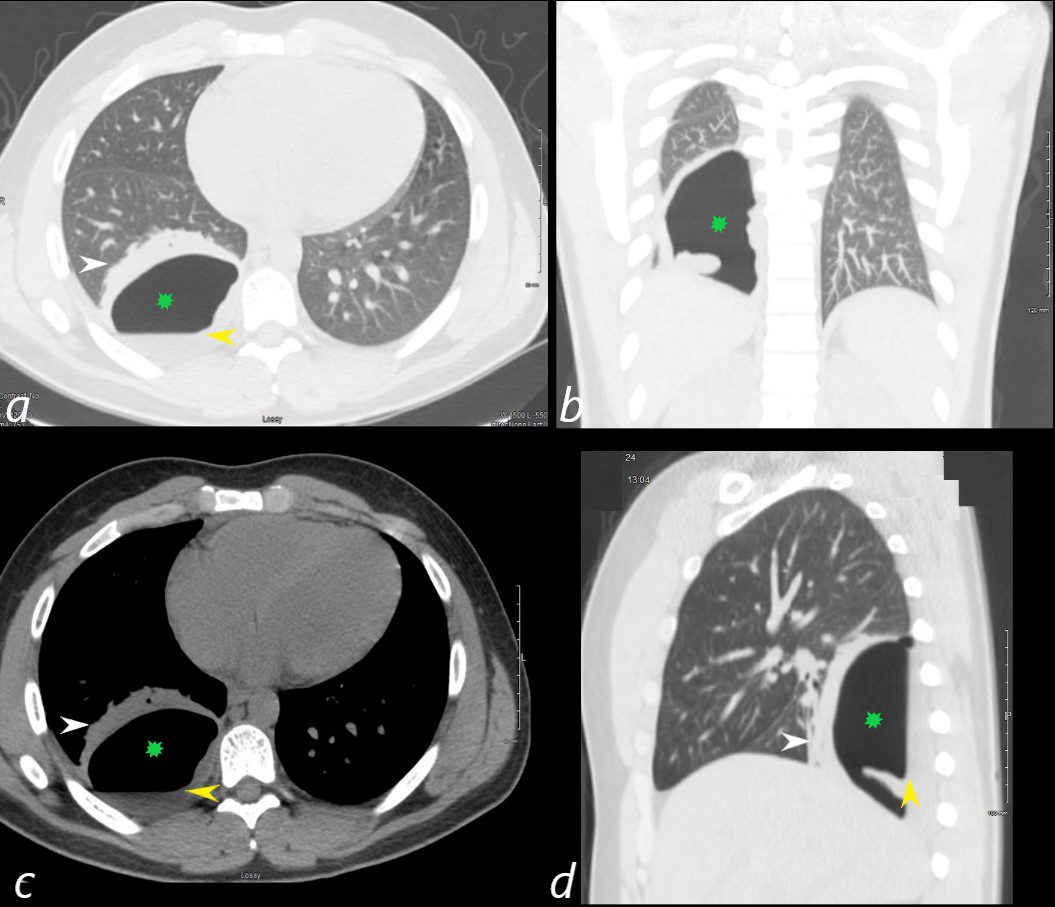

40 year old male with SLE presented with chest pain and dyspnea and initial CXR showed a vague retrocardiac density

A CT scan that followed showed occlusive pulmonary emboli to the left lower lobe (circled in white) associated with a wedge shaped infarct (red arrowhead)

Ashley Davidoff MD

key words

CT scan

SLE

PE

pulmonary embolism

pulmonary infarct

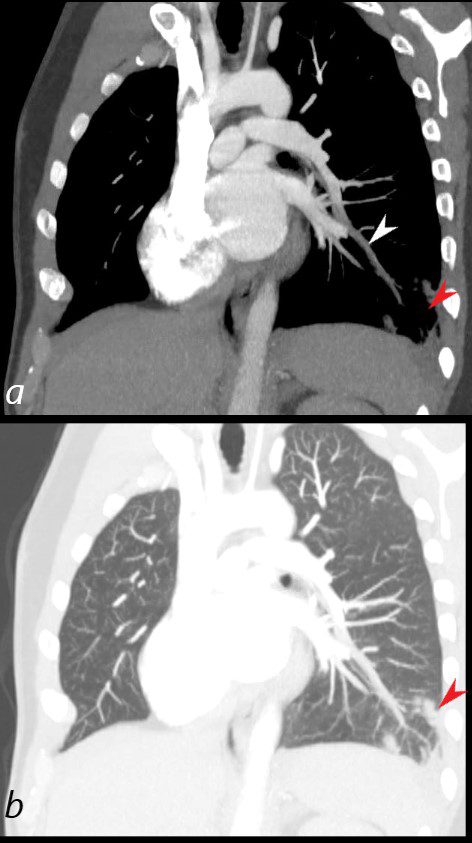

24 year old male with SLE presented with chest pain and dyspnea and initial CT showed occlusive pulmonary emboli to the right lower lobe initially associated with a wedge shaped ground glass region. 2 weeks later this evolved into a bronchopleural fistula, with a loculated pneumothorax in the right lower lobe (green star in a,b,c,d).with an air fluid level (yellow arrowhead in a,c,d) and a region of compressive atelectasis (white arrowhead a,c,d).

Ashley Davidoff MD

24 year old male with SLE presented with chest pain and dyspnea and initial CT showed occlusive pulmonary emboli to the right lower lobe (a,b, red arrowhead) with total occlusion of the right lobe artery extending into posterior basal segmental vessels (red ring d compared with normal vessels surrounded by white rin (d). An associated wedge shaped ground glass region is noted (e,f red arrowhead) representing either hemorrhage or early infarction

Ashley Davidoff MD

81-year-old male with weight loss, renal failure, and hemoptysis

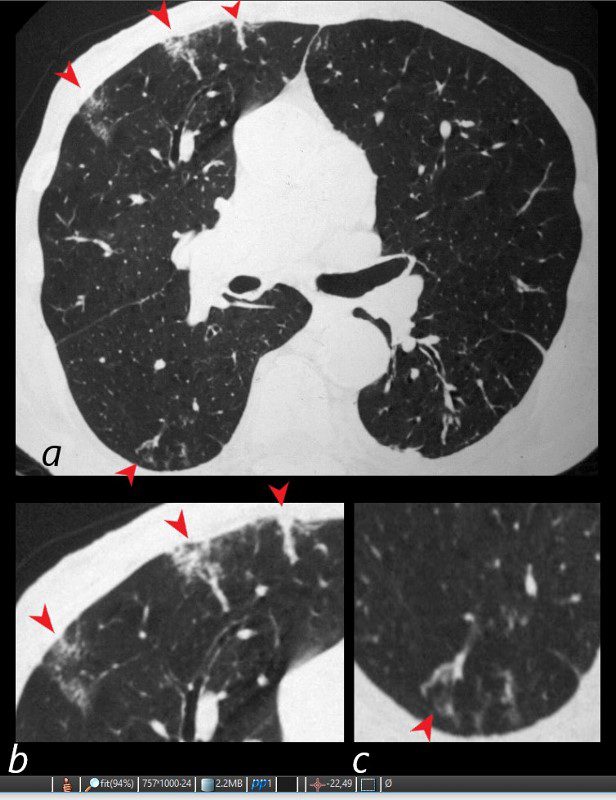

CT axial view (a) shows multiple peripheral wedge shaped ground glass densities subtended by distended feeding vessels (a,b,c, red arrowheads) reflecting areas of microinfarction due to vasculitis that affects both the arterioles and venules.

Priscilla Slanetz MPH MD

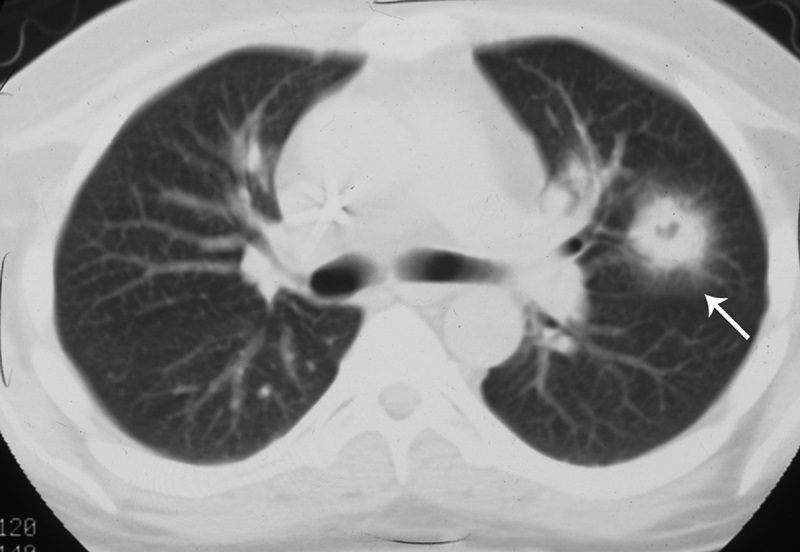

CT scan of a 67 year old female with anca vasculitis shows regions of dystrophic calcification in the lateral aspect of the right lower lobe (white arrow, a and b) )with focal nodular parenchymal consolidation, that likely reflects a site of prior small vessel infarct. Dystrophic calcification in the LV myocardium (blue arrows c) and a suggestion of fatty dysplasia in the left ventricular apex red arrow d) suggest changes from small vessel infarct. Ashley Davidoff MD

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging21(1):76-90, March 2006

The air crescent sign appears as a variably sized, peripheral crescentic collection of air surrounding a necrotic central focus of infection on thoracic radiographs (Fig. 1A) and CT (Fig. 1B).2–4 It is often seen in neutropenic patients who have undergone bone marrow or organ transplantation and is most characteristic of infection with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. The fungus invades the pulmonary vasculature, causing hemorrhage, thrombosis, and infarction. With time, the peripheral necrotic tissue is reabsorbed by leukocytes and air fills the space left peripherally between the devitalized central necrotic tissue and normal lung parenchyma.5 Thus, the presence of the air-crescent sign heralds recovery of granulocytic function.4 Other causes of the air crescent include cavitating neoplasms, bacterial lung abscesses, and infections such as tuberculosis or nocardiosis.6

CT halo sign

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

The CT halo sign appears as a zone of ground-glass attenuation around a nodule or mass (Fig. 7) on computed tomographic (CT) images.2–4,6,28 In febrile neutropenic patients, the sign suggests angioinvasive fungal infection, which is associated with a high mortality rate in the immunocompromised host.2–4 The zone of attenuation represents alveolar hemorrhage,2,4,6,28 whereas the nodules represent areas of infarction and necrosis caused by thrombosis of small to medium sized vessels.2–4,6,28,29 Other infectious causes include candidiasis, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and coccidioidomycosis.30 The CT halo sign may also be caused by non-infectious causes, such as Wegener granulomatosis, metastatic angiosarcoma, Kaposi sarcoma, and brochioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC).29,30 Due to the lepidic growth pattern of BAC, where the tumor cells spread along the alveolar walls, the typical ground glass halo visualized with the sign results.29

Hampton hump

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

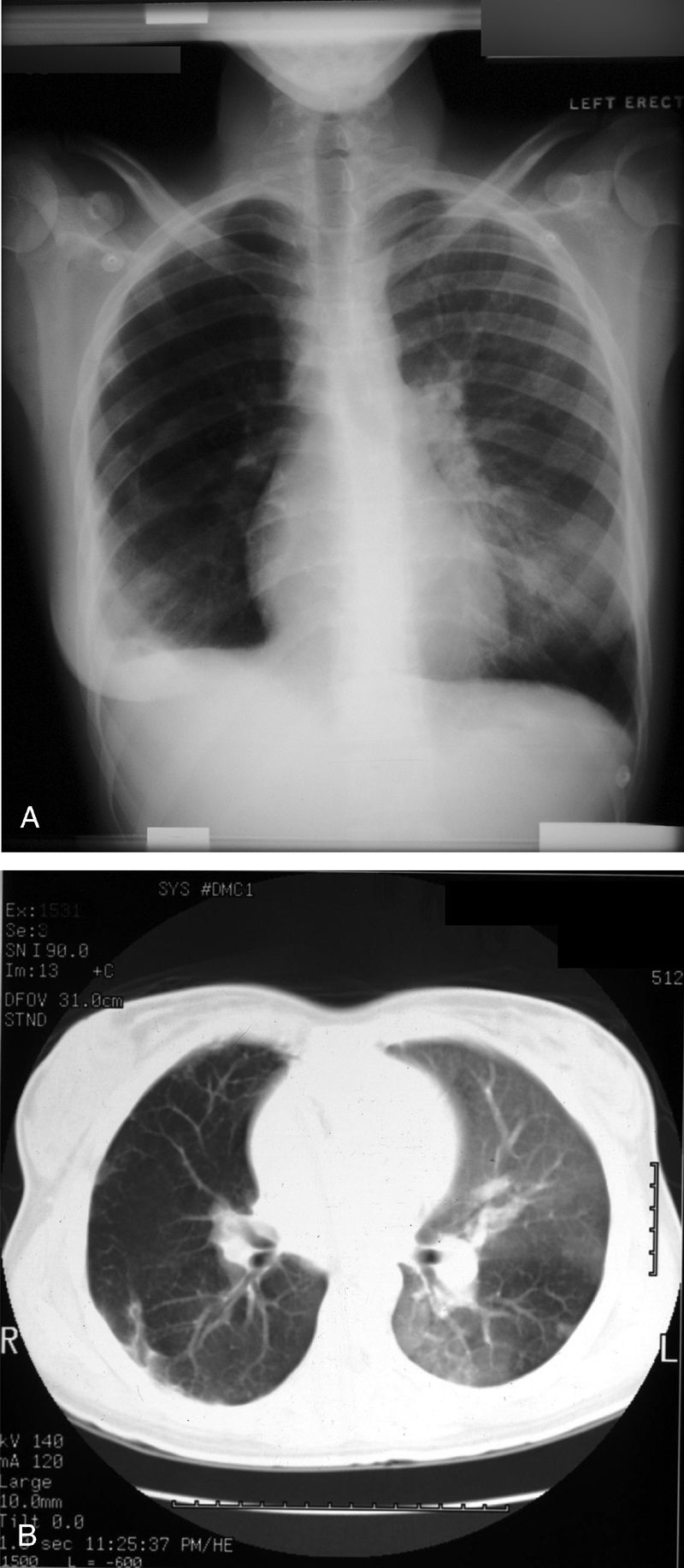

On plain radiographs (Fig. 14A) and CT (Figs. 14B, C), pulmonary infarcts are typically multifocal, peripheral in location, contiguous with one or more pleural surfaces, and more commonly confined to the lower lungs.3,47,48 The apex of these rounded or triangularly shaped opacities may point toward the hilum.3 The opacities resolve slowly over a period of several months, akin to “melting ice cubes,” and may leave a residual scar.3 The first documentation of the finding was made by Aubrey Otis Hampton, who was a practicing radiologist in the mid 1920s. He and his co-author Castleman first reported evidence of incomplete pulmonary infarction in the setting of PE in the 1940s.47,48 Autopsy follow-up showed evidence of intra-alveolar hemorrhage without alveolar wall necrosis in the first 2 days of infarction. After 2 days, wall necrosis begins and eventually leads to pulmonary infarction and an organized scar.47,48 Hampton also observed that there were differences in the healing of these incomplete infarcts depending on their premorbid cardiac history.47,48 In patients without heart disease, the incomplete infarcts would generally heal without scarring, whereas patients with congestive failure were more likely to progress to infarction with a persisting pulmonary scar.47,48 When pulmonary embolism results in infarction, airspace opacities typically develop within 12 to 24 hours.3,48

Westermark sign

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

Neil Westermark was a 20th-century German radiologist who first discovered that a certain subset of patients diagnosed with pulmonary embolism (PE) were complicated by pulmonary infarction.64 He described the “anemic” or oligemic peripheral regions of lung parenchyma as “wedge-shaped shadows.” Interestingly, he also found that the majority of patients with PE did not have pulmonary infarcts, a finding that has been affirmed in the more recent literature.47 The chest radiograph (Fig. 24A) and CT (Fig. 24B) findings of increased translucency (chest radiograph) or hypoattenuation (CT) corresponding to oligemia in the periphery of the lung distal to an occlusive arterial embolus is typical.3,4,64 Visualization typically signifies either occlusion of a larger lobar or segmental artery or widespread small vessel occlusion.4,64