In a Nutshell

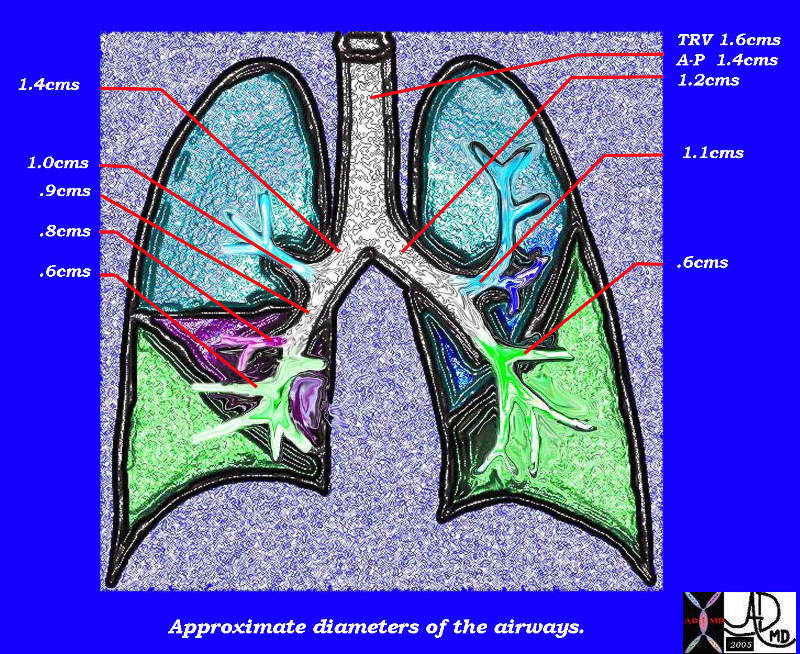

- Size 1.4cms 1.1cms

-

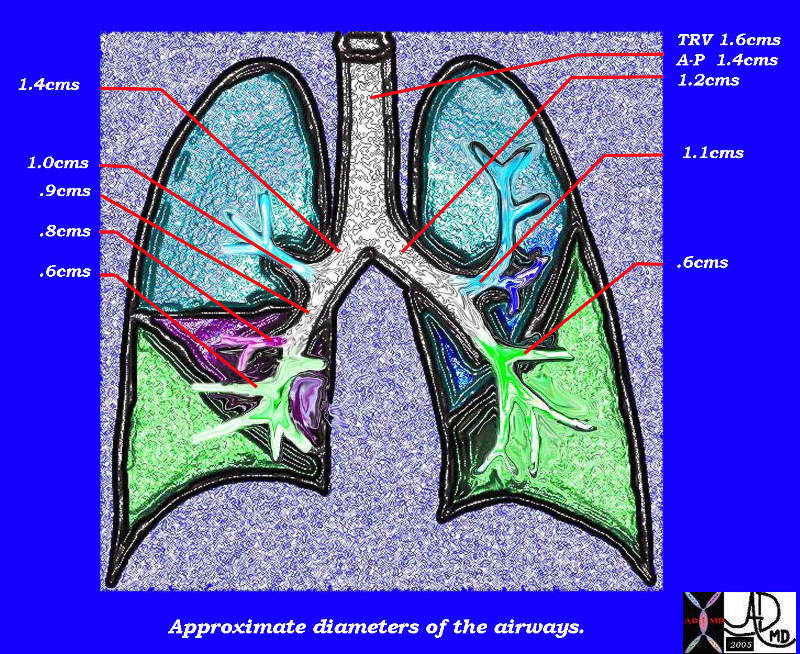

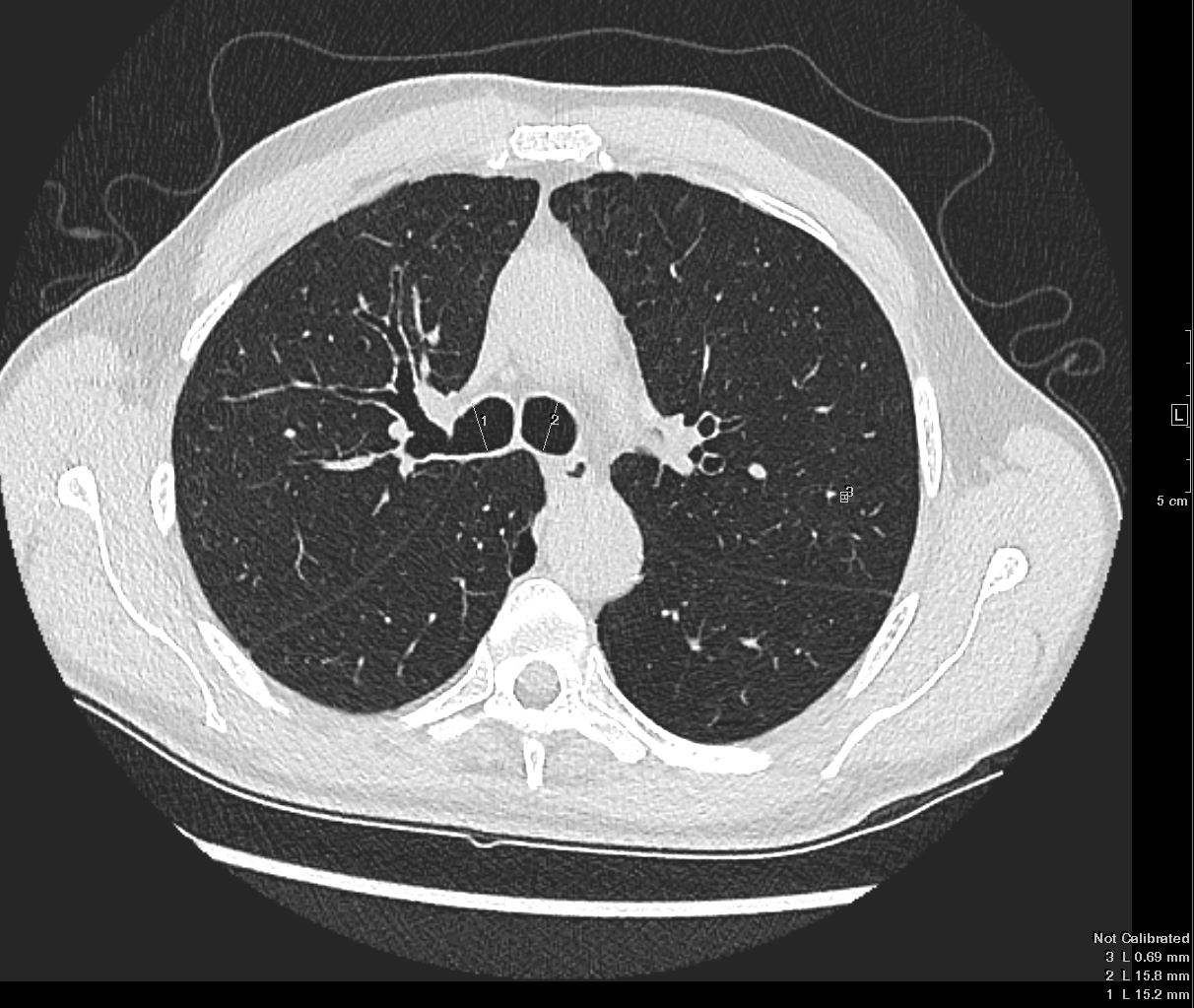

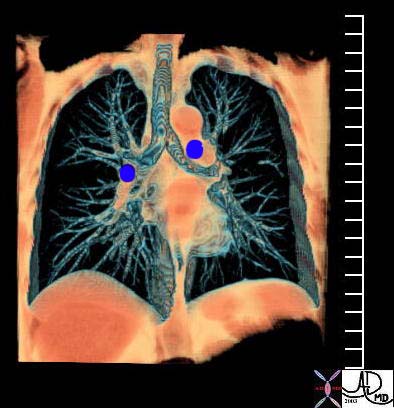

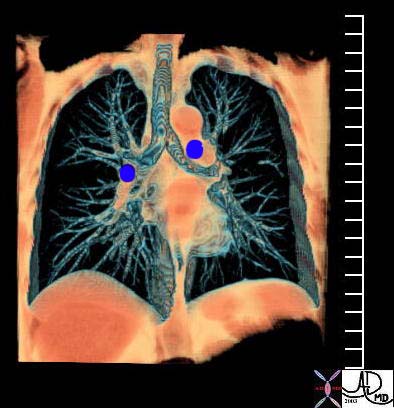

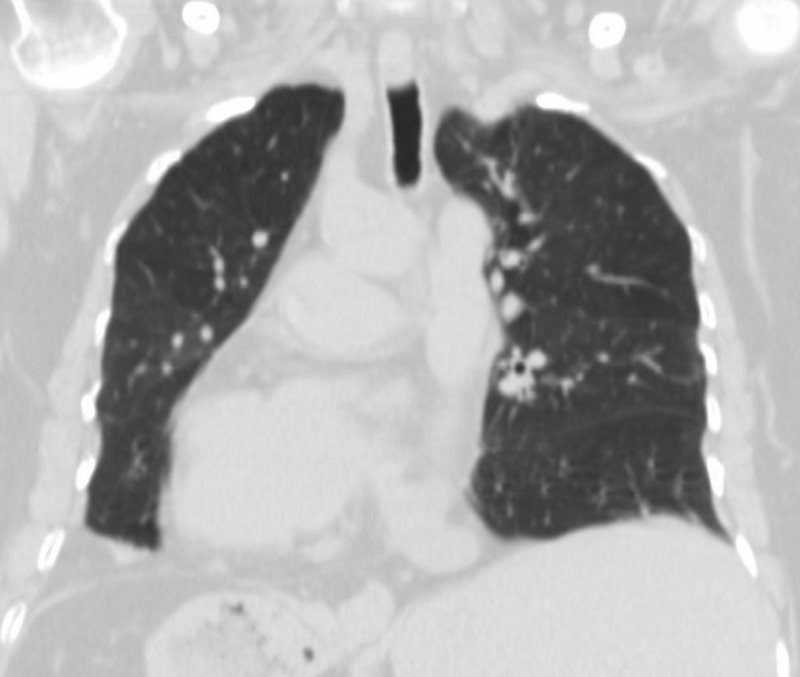

Diameters of the bronchi

This diagram of the airways reveals the approximate diameters of the airways. Note that the left main stem bronchus is thinner than right whose length is truncated by the take off of the right upper lobe bronchus.

Ashley Davidoff MDTheCommonVein.net

32686b05L05b - right short and fat

- left long and thin

-

TRACHEOBRONCHIAL TREE

The right mainstem bronchus is short and fat and arises with a relatively acute angle from the trachea, whereas the left is long and thin, and arises with a relatively acute angle. The acute angle of the right main stem bronchus predisposes a misplaced trachea or aspirated foreign bodies travelling down the right bronchus

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net -

The Carinal Angle and ….. OLIVER HARDY AND STAN LAUREL IN THE 1939 FILM – THE FLYING DEUCES Short and Stout Long and Thin

-

- Shape

- Round

- Position

- above the left atrium

- applied anatomy

- above the left atrium

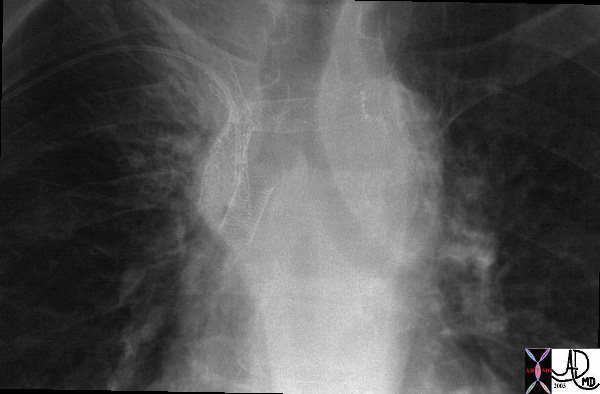

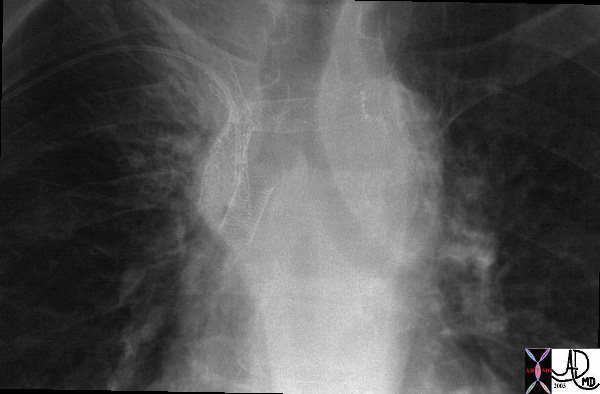

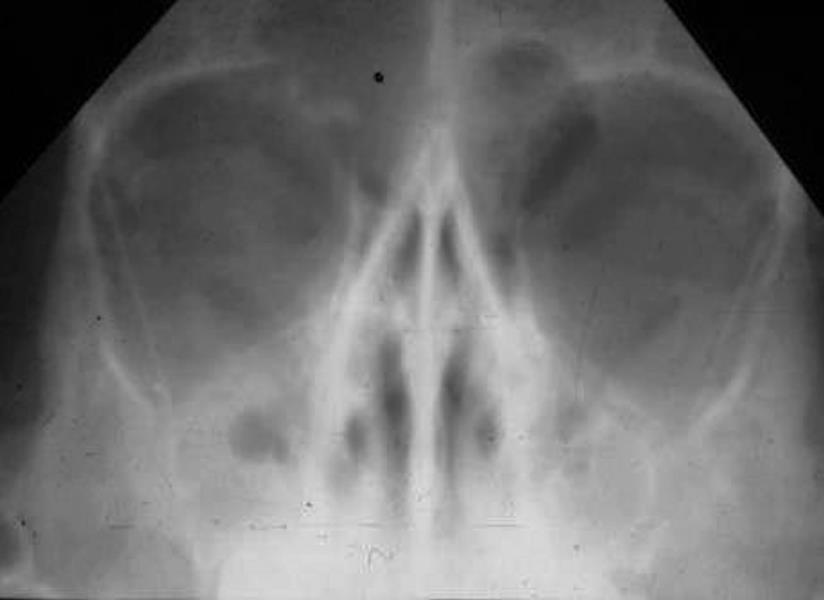

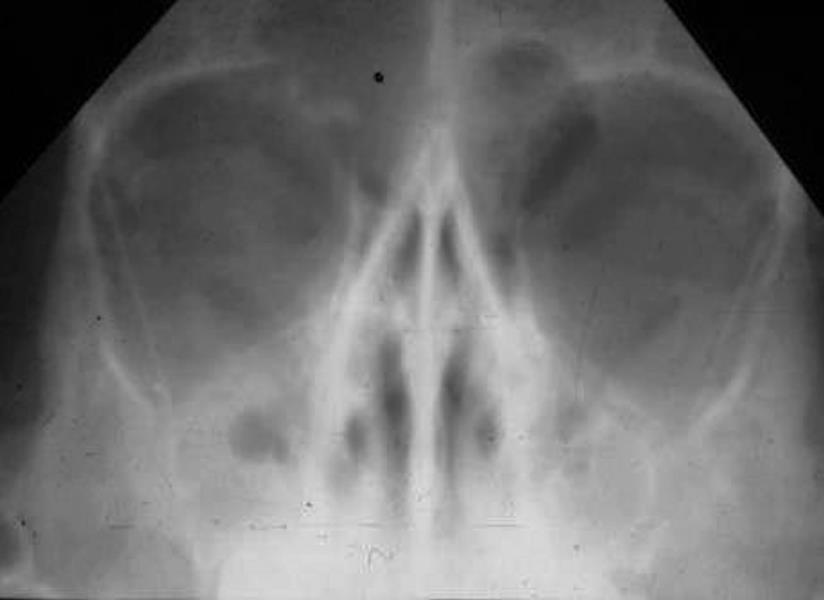

Kartagener’s (Immotile Cilia) Syndrome- Situs Inversus Dextrocardia

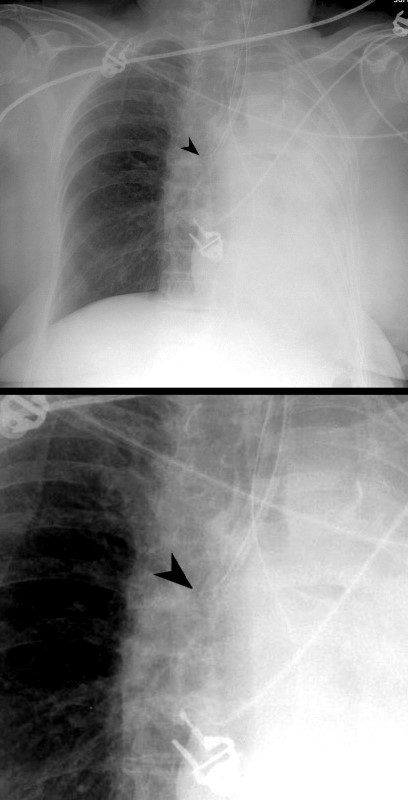

This 30 year old male presents with a long standing history of a productive cough, headaches, and infertility. This obsolete study called a bronchogram outlines the bronchi with contrast revealing situs inversus of the bronchi. In the right upper lobe there are saccular accumulations of contrast representing a region of bronchiectasis. The stomach bubble can be seen on the right and hence there is situs inversus totalis. The heart is seen with apex pointed to the right and hence there is dextrocardia. So we can explain the cough from the bronchiectasis, but how do we explain the headaches and the infertility?

Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD 06248

SITUS INVERSUS OF BRONCHI,- HYPARTERIAL BRONCHUS ON RIGHT, EPARTERIAL BRONCHUS ON LEFT

62 year old female with situs inversus totalis, dextrocardia, {SLL} heart, inversus of the lungs, left sided liver, right sided stomach and spleen, bronchiectasis, and chronic sinusitis.

aka Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD), is a rare, ciliopathic, autosomal recessive genetic disorder

Ashley Davidoff MD

- Character

-

- cartilaginous rings

-

- Time

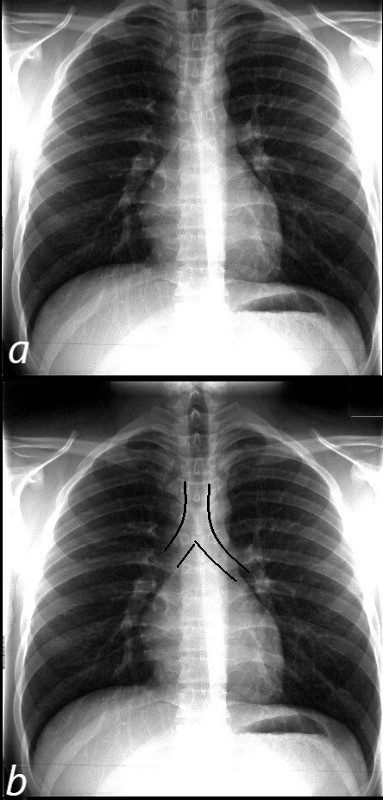

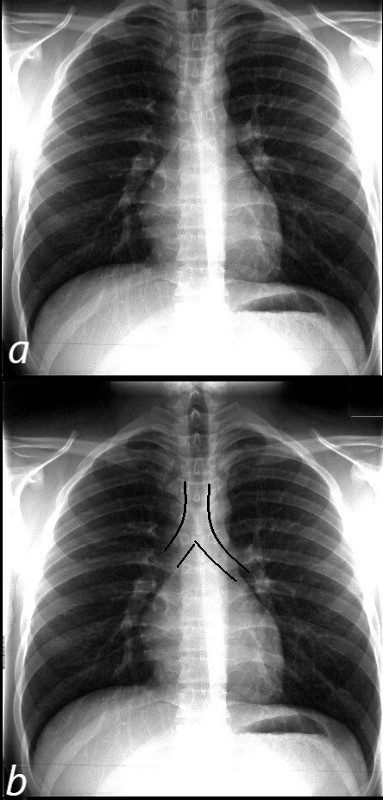

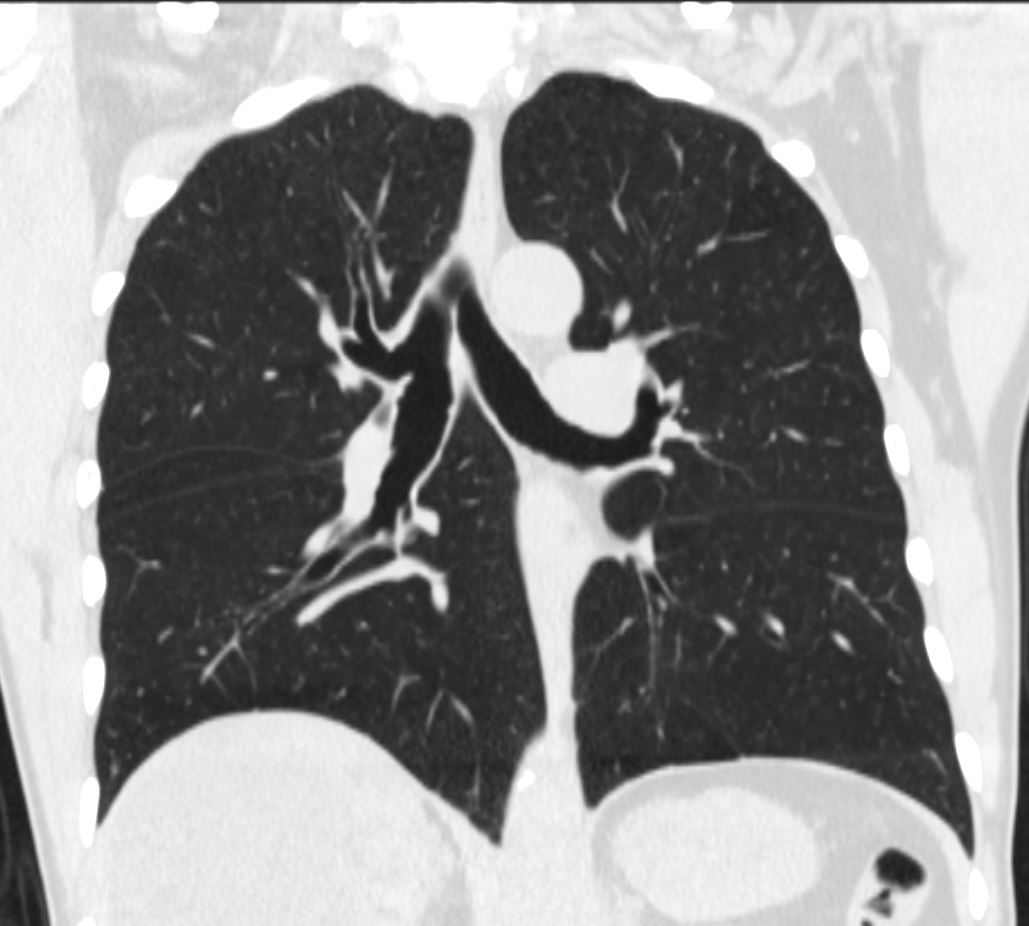

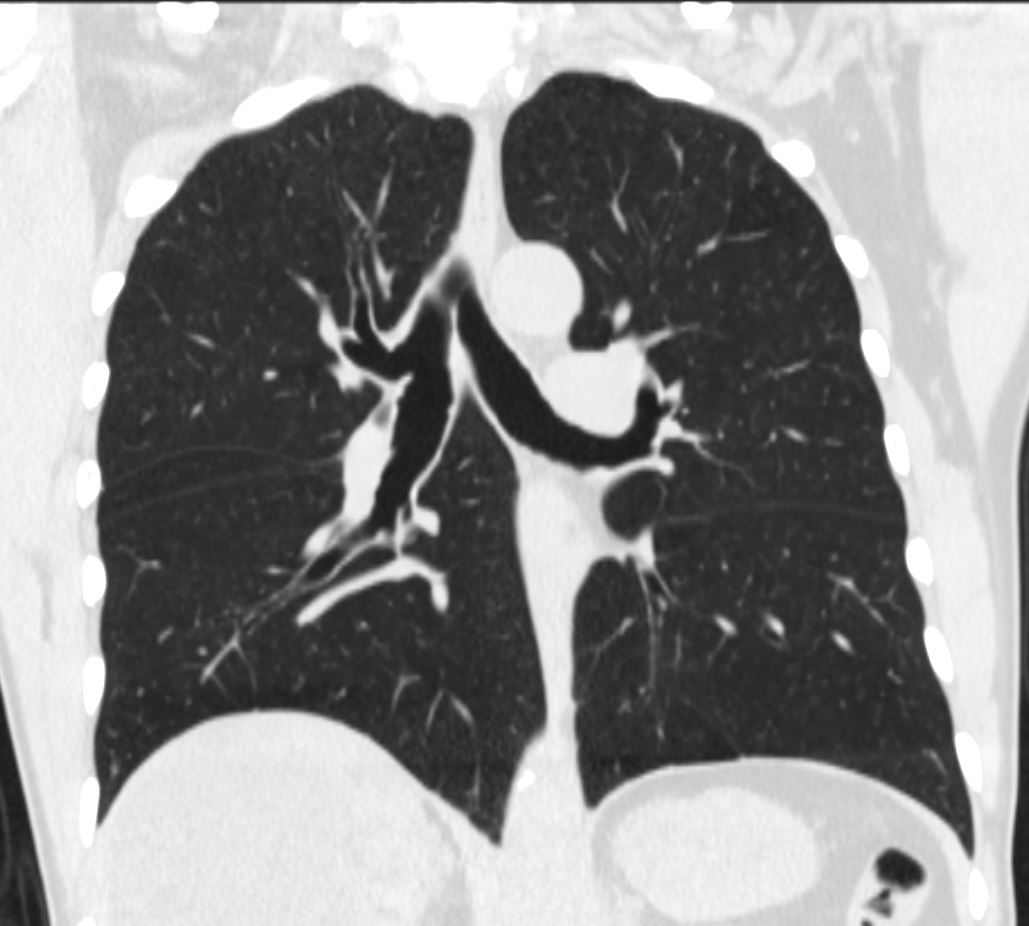

The normal CXR shows the characteristic asymmetric branching of the main stem bronchi. The right is short and stout and slightly more vertical while the left is long and thin and slightly more obtuse.

The normal carinal angle is between 40-80 degrees.

Ashley Davidoff MD

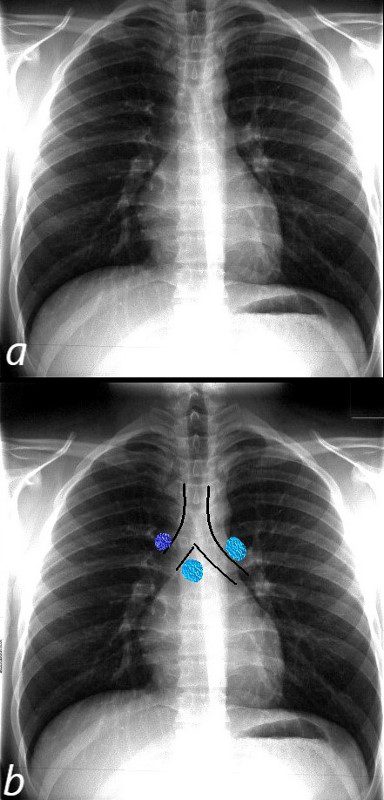

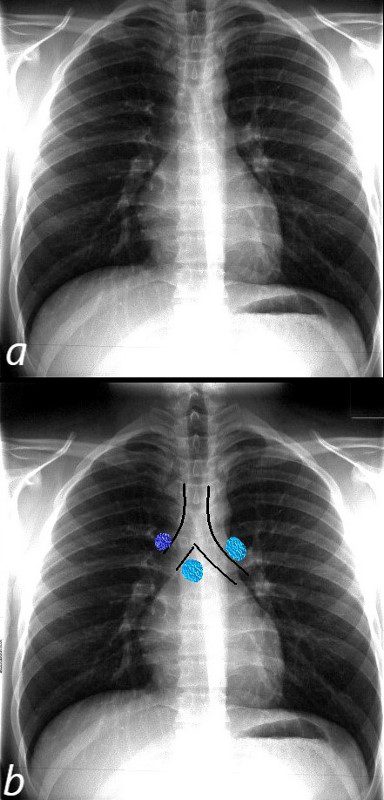

The normal CXR shows the superior position and relationship of the LPA to the left mainstem bronchus. The bronchus is hyparterial ie below the artery.

The RPA (light blue and right in b) runs below the right mainstem bronchus ie the bronchus is eparterial . The azygos vein lies superior to the right mainstem bronchus at the take off of the right mainstem from the trachea.

Ashley Davidoff MD

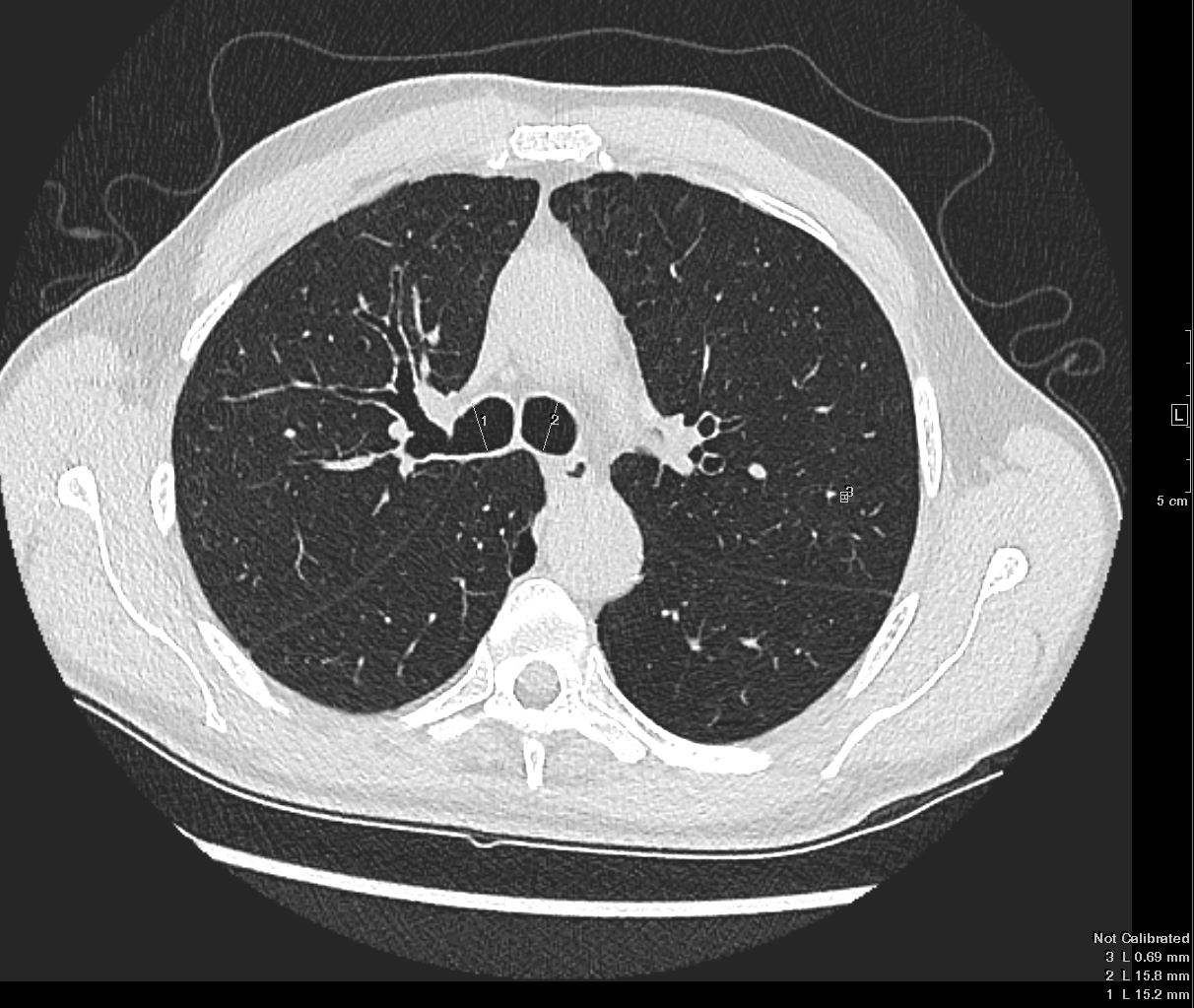

Bronchi – diameters

Consideration of the size of the conducting system as a tubular and transporting system where diameter and length are functionally relevant is far different from the considerations given to the gas exchange system where surface area is the prime functional consideration. Measurements of the larger airways have practical significance for the bronchoscopist who has to know how far it is possible to advance the bronchoscope into the airways, for the anesthesiologist who needs to intubate the patient, and for the interventionalist who may need to stent a stenotic segment. The smaller airways are more difficult to measure but in general they should approximate the size of the accompanying arteries.

The mean transverse dimension of the trachea is 1.6cm, ranging from 1.3- 2.5cms in the male and from 1-2.1cms in the female. The mean A-P dimension is slightly less, measuring 1.4cm.

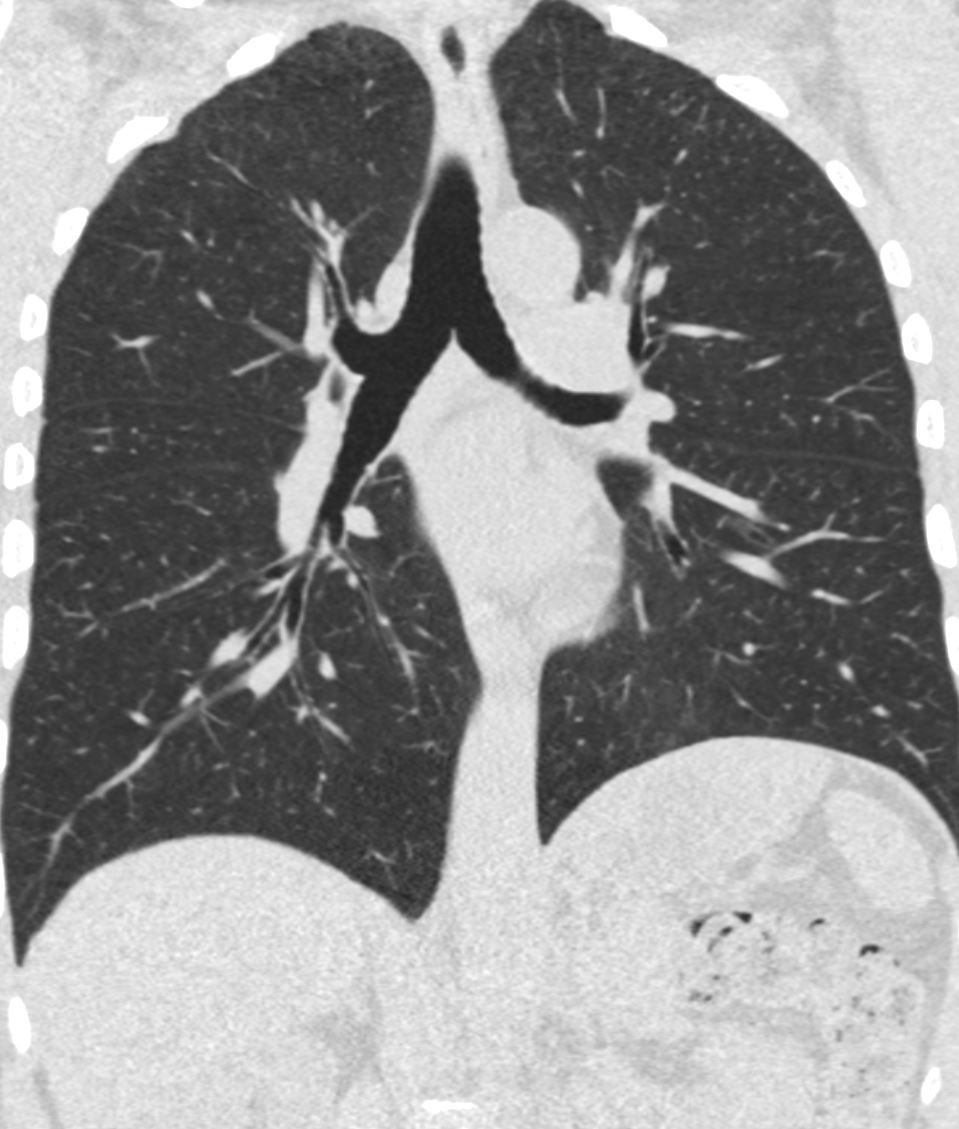

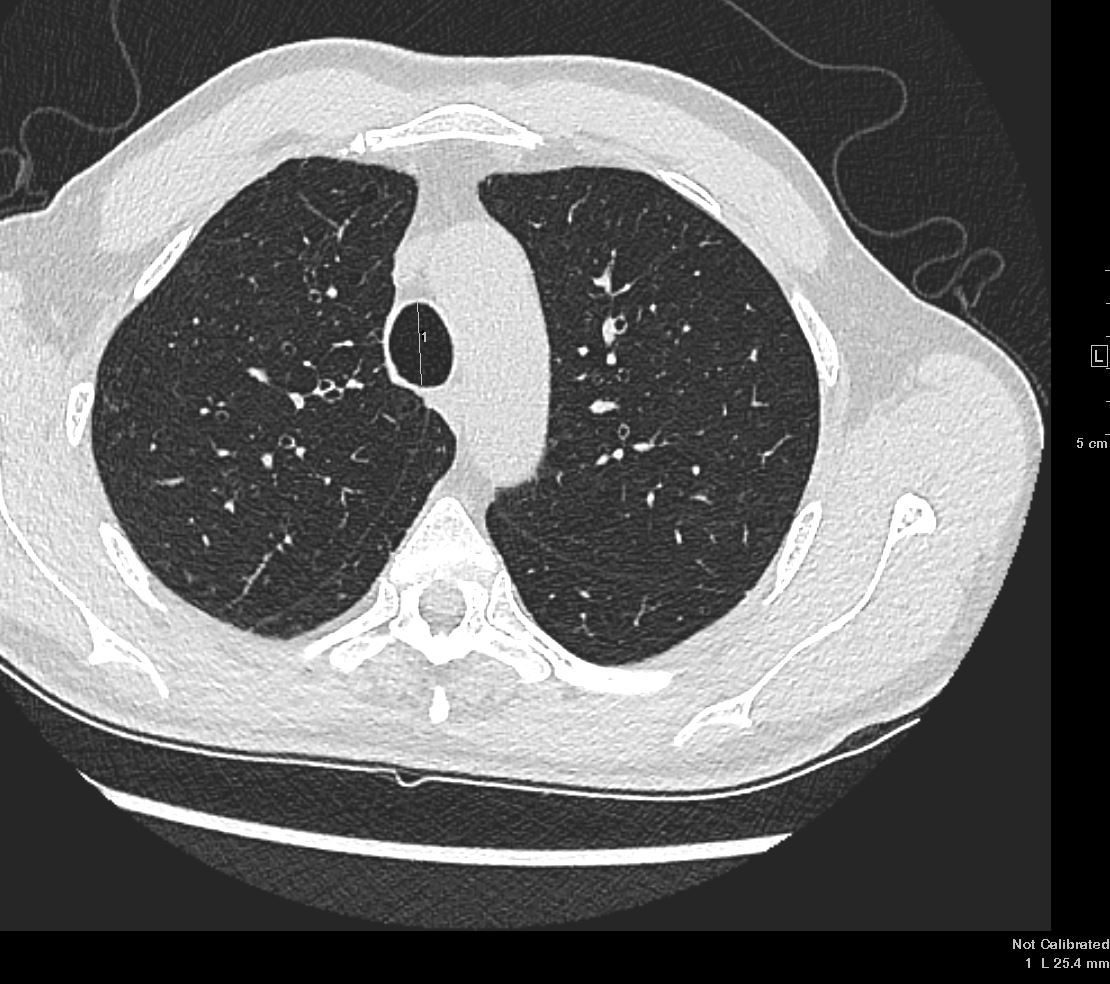

Normal chest CT of the upper lobes of both lungs showing the trachea. The transverse dimension of the trachea at this level is slightly larger than its A-P dimension, and both are slightly smaller than the diameter of the aortic arch.

Ashley Davidoff TheCommonVein.net 32158

The mainstem bronchi taken together have 40% more cross sectional area than the trachea. This progressive increase in cross sectional area continues as we progress downstream resulting in an overall reduction in resistance, evolution of laminar flow, and facilitation of airflow. This structural feature allows air from a single breath to reach all the alveoli virtually simultaneously.

There is considerable discrepancy in the diameter and length between the right and left mainstem bronchi. The right mainstem bronchus is known as the short and plump member of the family while the left mainstem bronchus is the long and thin one.

The right mainstem bronchus measures about 1.4 cms while the left mainstem bronchus is about 1.3cms both being slightly smaller in the female (Hampton , et al).

This diagram of the airways reveals the approximate diameters of the airways. Note that the left main stem bronchus is thinner than right whose length is truncated by the take off of the right upper lobe bronchus.

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net

32686b05L05b

The RUL bronchus is about 1 cm in diameter, with the apical segment being 4-7mm, and the RML bronchus is about 8mms. The LUL bronchus resembles its uncle, the right main stem bronchus, since it is also relatively short and fat possibly because it is responsible to give rise to the lingula as well as the left apical segments. It measures 11mm mm in diameter (but only 9mm in length). The ascending upper division bronchus is approximately 7 mm in diameter.

General diameters of the downstream airways include lobular and segmental bronchi (5-8mm), subsegmental bronchi and bronchiole (1.5-3mm), lobular bronchiole (1mm), terminal bronchiole (.7mm) and acinar bronchiole (.5mm). (Webb Muller Naidich)

The acinus is about 7-15 mms in diameter.

Applied Anatomy

In Part 1 we learned how radius and flow were related. When the flow is laminar as it is in the smaller airways Poiseuille’s law applies which states the following

Volume flow rate = pressure difference

resistance

= P1-P2

R

= pressure difference X radius4

8/pi viscosity X length

Thus it can be seen that a small change in the radius makes a major difference in the volume flow rate. Number of divisions and length are other key considerations in flow but they do not carry the same power as radius. Narrowing of the airways at any level significantly affects delivery of air downstream.

Size Change

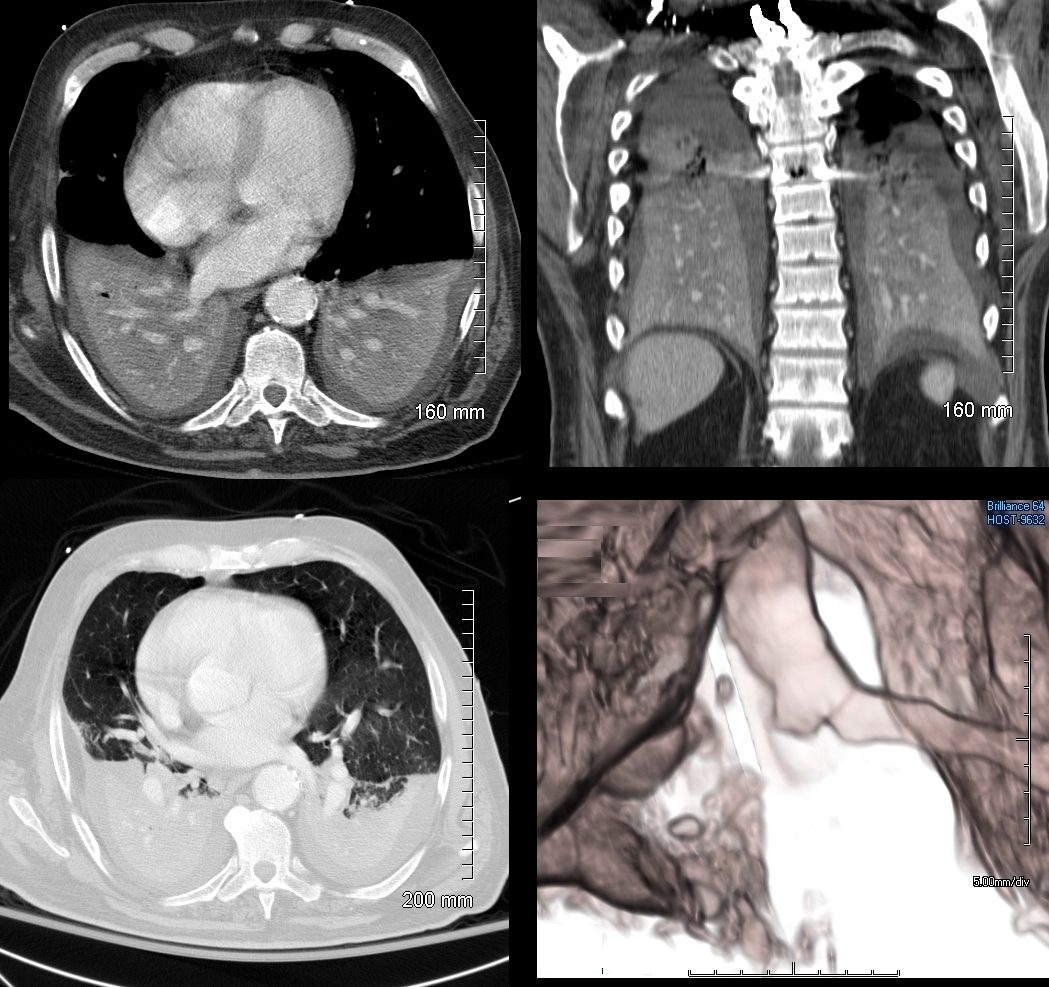

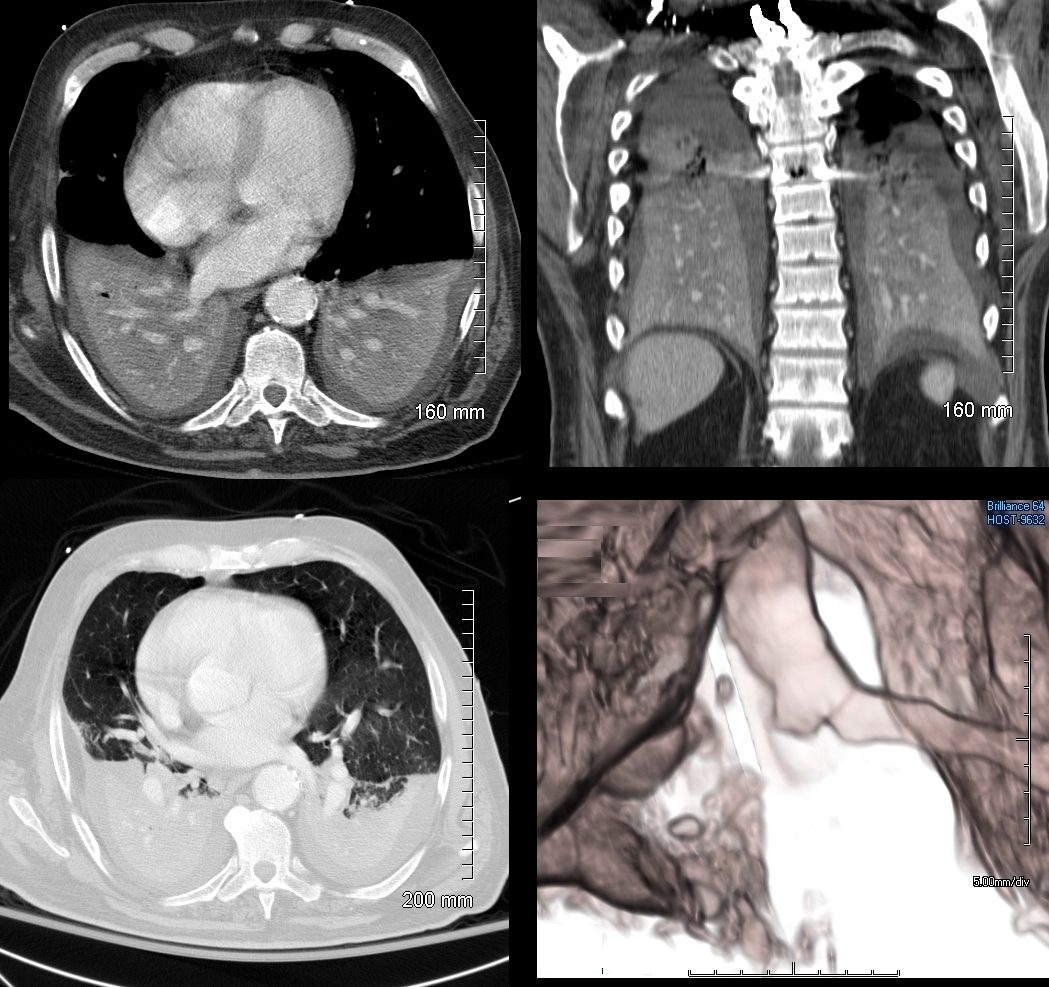

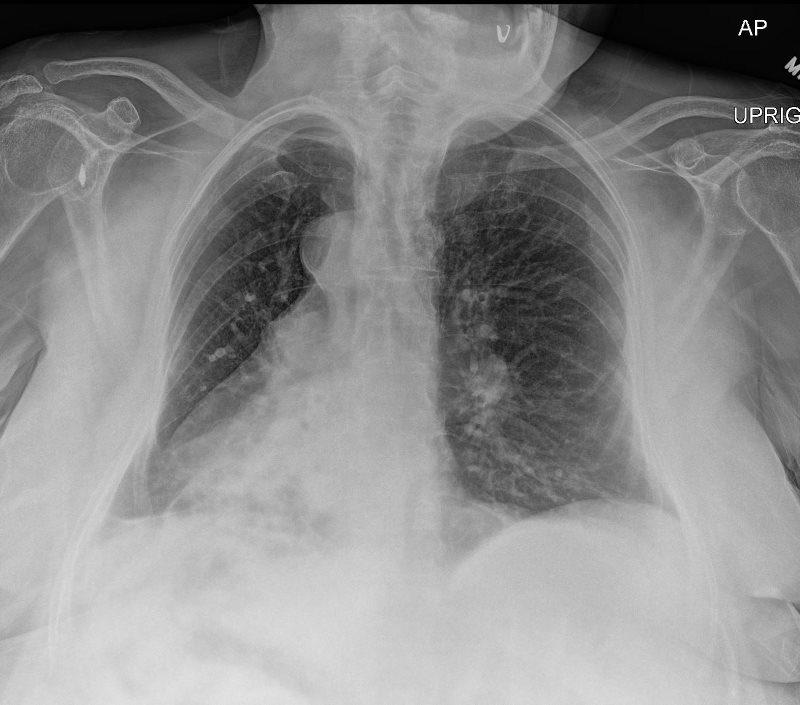

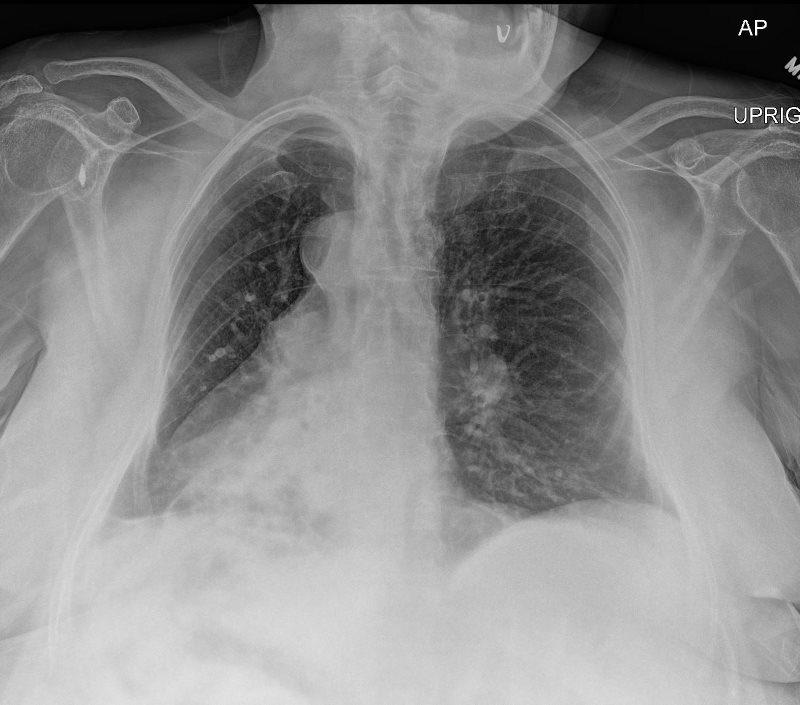

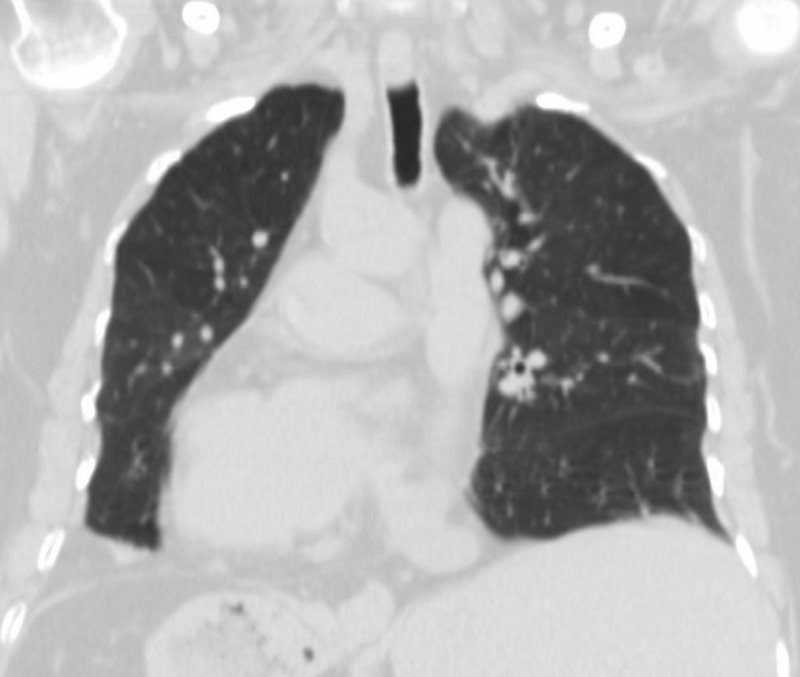

66 year old male with COPD

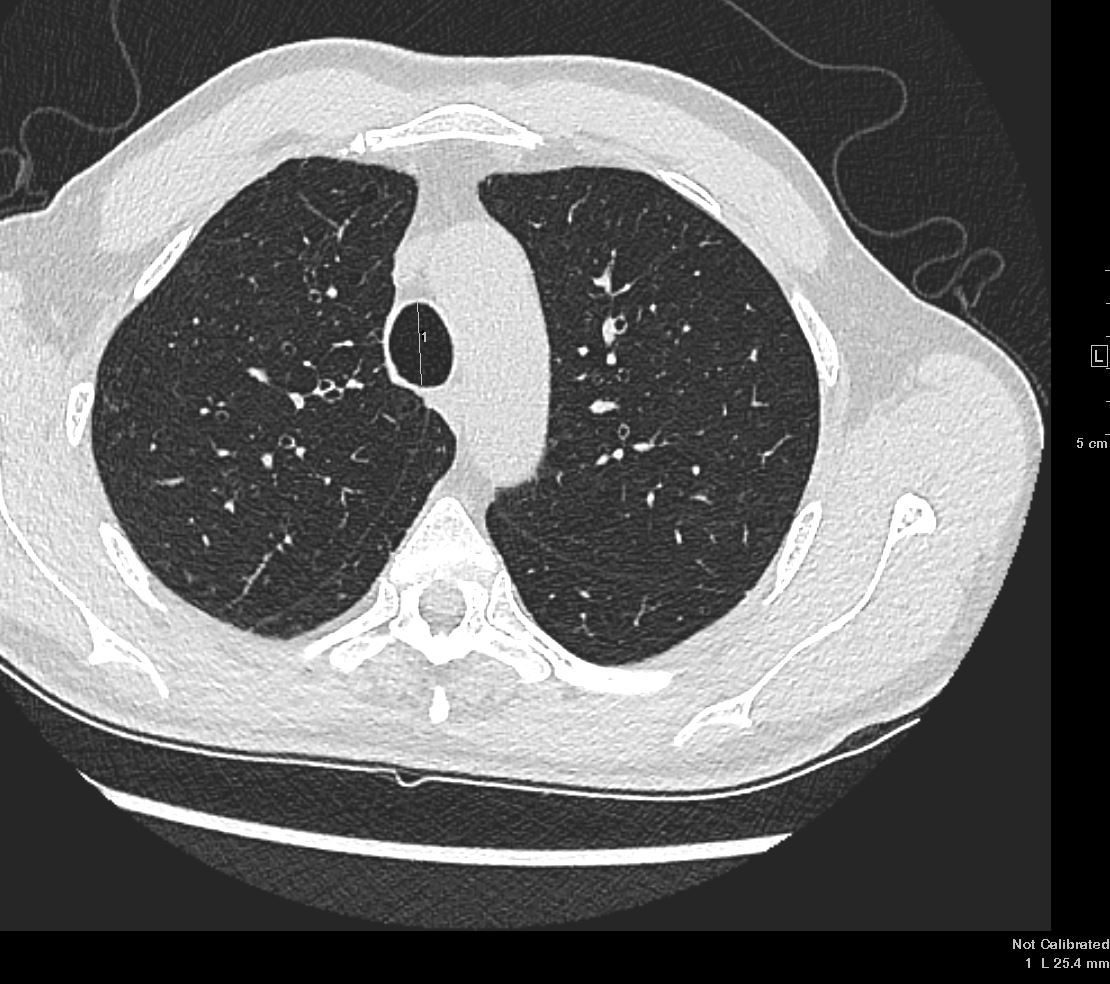

Trachea and Bronchi Upper Limits Normal in Size

Trachea and Bronchi Upper Limits Normal in Size

Ashley DAvidoff TheCommonVein.net

Trachea and Bronchi Upper Limits Normal in Size

Ashley DAvidoff TheCommonVein.net

Trachea and Bronchi Upper Limits Normal in Size

Ashley DAvidoff TheCommonVein.net

Trachea and Bronchi Upper Limits Normal in Size

Ashley DAvidoff TheCommonVein.net

Trachea and Bronchi Upper Limits Normal in Size

Ashley DAvidoff TheCommonVein.net

Trachea and Bronchi Upper Limits Normal in Size

Ashley DAvidoff TheCommonVein.net

Trachea and Bronchi Upper Limits Normal in Size

Ashley DAvidoff TheCommonVein.net

The failure of air delivery is one of the major causes of fatality during an anaphylactic reaction or a severe asthma attack. Return of airway patency is the first consideration in resuscitation. In fact, in any resuscitation, the “A” of the “ABC” of resuscitation is to ensure patency of the airway first.

Maintenance of airway diameter is provided by cartilage in the upper components of the airways. In the trachea a C-shaped cartilaginous ring surrounds the anterior and lateral walls while the posterior wall consists of a membrane allowing for some pliability during the phases of respiration. The trachea lengthens and dilates during inspiration while it shortens and narrows during expiration.

Some disease states compromise the patency of the airways. Tracheomalacia is a softening of the cartilage of the trachea and during inspiration the trachea will be unable to maintain its diameter. This will result in a relative collapse during inspiration and hence diminished air flow.

More downstream, support of airway patency transforms from cartilaginous support to muscular support. Asthma, inflammation, or infection can affect the diameter by inducing muscle spasm while the presence of edema of the wall would also result in narrowing of the lumen. In most of these diseases the airways of both lungs are diffusely involved and respiratory decompensation can easily result. Collapse of a lobe, segment, or sub segment of a lung on the other hand may not affect respiratory function at all when the remaining lung is normal or near normal. Localized collapse may occur with foreign body inhalation, mucus or purulent impaction, and tumor growth. Patients who have undergone a pneumonectomy normal pulmonary function usually exists, unless there is disease in the other lung.

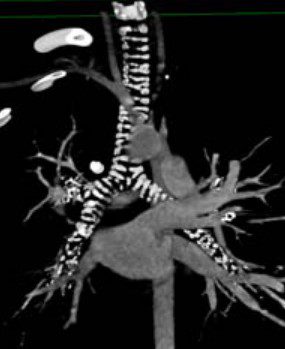

74 year old male alcoholic with bilateral basilar lobar atelectasis caused by bilateral aspiration

CT scan shows airless lower lobes with small bilateral effusions. 3D reconstruction shows total obstruction of the right mainstem bronchus, and patent proximal mainstem bronchus

Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net

This is a case of a central squamous carcinoma causing obstruction of the right mainstem bronchus and SVC requiring stents in both. This image tells the story of how tubular transport function is compromised by reduced size, and how size can be restored by modern technology.

Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD

TheCommonVein.net

0916030018

The main pulmonary artery (MPA) is usually about 3-4 cm in diameter being very similar to the ascending aorta and twice the size of the trachea. The branch pulmonary arteries are each about the same size as the trachea. Although the right and left mainstem bronchi are in combination and thus the RPA and LPA are quite a bit larger than their counterparts the right and left mainstem bronchi. However, at the segmental level there is a catch up, so that the bronchi and arteries are equal in size.

These comparative sizes are very important in the imaging world and size evaluation is very useful in the diagnosis of tracheomalacia, COPD (big trachea), tracheal narrowing, bronchiectasis, aortic aneurysm, pulmonary congestion, and pulmonary hypertension – all common medical conditions that have characteristic changes in size that are evaluated by comparing the sizes of the airways to the vessels. It should be noted that in dependent positions the artery might normally appear slightly larger than its airway counterpart. This means that if the patient is supine blood will be more dependent posteriorly and so the posterior vessels may be slightly larger than their bronchial brother or sister. The reason we are able to see the air filled bronchi within the air filled lung is because they have wall that is made up of the soft tissue allowing for an interface. As the bronchi get smaller their walls will get proportionately thinner until they are too thin to resolve at which time they will blend into the parenchyma. They become invisible as discrete structures on high resolution CT when they reach 2mm in size, which corresponds to the bronchioles that are about 2cms from the lung periphery. The arterioles on the other hand maintain their soft tissue character and their interface with air of the lung is maintained allowing detection even in subpleural regions of the lung periphery.

Length of the tracheobronchial tree

The length of the airways does have practical significance as well, contributing to velocity of flow as defined in the Poiseuilles law (see below). Knowledge of the length of structures is also important for safe execution of procedures such as endoscopy, intubation, and stent placement.

Ashley Davidoff M.D. TheCommonVein.net 32682

This diagram of the airways reveals the approximate lengths of the airways. Note that the left main stem bronchus is about twice the length of the right whose length is truncated by the take off of the right upper lobe bronchus.

Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD

TheCommonVein.net

32686b05L04b

In adults, the trachea ranges from 9 to 15 cm in length, terminating distally at the carina which represents the origins of the left and right mainstem bronchi. The distance from mouth to carina is about 25cms.

As previously stated the right and left bronchus show considerable difference in their morphology. The right is short and plump while the left is long and thin.

The right bronchus is on average about 1.2cms long, but it can be as long as 2.9cms. (Robinson et al ) It is wider, shorter, and more vertical in direction than the left. About 2 cm from its origin it gives off a branch to the upper lobe of the right lung.

The left bronchus is nearly 5 cm long. It is therefore more than twice the length of the right but it is smaller in diameter.

The RUL bronchus is about 1cm in length. The apical bronchus is about 2cm in length.

The RML bronchus is 1.2cm. The RLL basilar trunks average length measures, approximately 15 mm.

The LUL bronchus is short and fat and takes after its uncle on the right (right mainstem) – it measures 9 mm in length (but 12mm in diameter). The ascending upper division bronchus on average is 1 cm in length.

Other Important Dimensions in the Airways

Angles

The left main stem bronchus leaves the trachea at a 135-degree angle. The right mainstem bronchus is more vertically oriented, with a 155-degree angle of origin. The carinal angle should be about 55 degrees and should not be more than 90 degrees. In patients with subcarinal disease including pathological lymph nodes (lymphoma and metastatic lung carcinoma), left atrial enlargement (mitral stenosis, regurgitation and left heart failure), and large hiatus hernia, the carinal angle may be widened. The carinal angle is therefore a very important landmark in the evaluation of the chest X-Ray.

Area

Cross-sectional area of the airways

Trachea approximately 2.5 cm2

Alveoli approximately 11,800 cm2

Position of the Tracheobronchial Tree

The trachea is central in its position, and lies anterior to the esophagus. It originates below the pharynx and ends at the carina where it bifurcates into left and right main stem bronchi. The right bronchus lies more vertical in its axis than the left. When we look at a normal CXR we find that the right hilum is slightly lower than the left. Since the hilum is made up of vessels and airways and since the RPA runs below the right mainstem bronchus the superior most structure in the right hilum is the bronchus. The left bronchus is hyparterial, meaning that it runs below the LPA. (i.e. the LPA does the high jump over it) Thus the left hilum is higher than the right. The RPA cannot make the jump over the right mainstem bronchus, (called the eparterial bronchus) resulting in a right hilum that is slightly lower than the left.

Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net

Applied Anatomy

Knowledge of the relationship of the trachea and esophagus is extremely important for those who are intubating patients or placing nasogastric tubes. The trachea and esophagus lie very close to each other, and so it is not uncommon for the intubations to be misplaced.

Upper lobe disease such as TB will cause fibrosis and shrinkage of the lung structures with consequent traction effect and elevation of the hilum so that it is pulled upward.

The CXR of this patient shows retraction of the left hilum so that it lies higher than it should. Linear atelectasis identified in the LUL. This correlates with the finding on the CT accounting for the volume loss and elevation of the left hilum. Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net 30562

In this patient with TB there is a linear band like density with calcifications in the LUL characteristic of atelectatic change in the RUL. This loss of volume is associated with fibrosis and retraction seen on the CXR in the following image. Ashley Davidoff MD TheCommonVein.net 30557

In situs inversus the right and left lung are reversed, so that the left lung is positioned in the right chest and the right lung in the left chest. The chest X-ray is the best and easiest way to make this diagnosis, since the air filled bronchi are easily seen. If the long and thin brother lies on the right, and the short and fat brother lies to the left, the condition of situs inversus of the lung exists. In this instance the anatomically left lung consists of two fissures (oblique and transverse) and three lobes LUL, LML, and LLL, while the anatomically right lung only has an oblique fissure and consists of a RUL (with lingula) and RLL. Inversus of the lungs does not necessarily imply inversus of the abdominal viscera. In the presence of situs inversus of the lungs it is incumbent on the radiologist to identify the position of the stomach bubble on the presenting CXR. If it lies to the right then situs inversus totalis exists. The CXR, more than 100 years old, still holds the key to many fancy diagnoses but one can only see what one looks for – and one can only look for the things that one knows. Sherlock Holmes was more eloquent with this sentiment exemplified by the following quote from the story entitled “A Case of Identity”

“Not invisible but unnoticed Watson. You did not know where to look so you missed all that was important” Making the diagnosis of situs inversus totalis based on the CXR is quite a feat but it requires a knowledgeable and inquiring mind similar to that of Sherlock Holmes. One can only see what one knows.

Immotile ciliary dysmotility syndrome (aka immotile cilia syndrome), is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder with genetic heterogeneity, characterized by abnormal ciliary function. The effects are systemic and all cells that have cilia are compromised, including the mucosa of the airways and sperm. Poor ciliary function in the airways results in reduced mucosal immunity and poor clearing of mucus, and the syndrome is complicated by recurrent bronchitis, pneumonia, bronchiectasis, and sinusitis. Dysfunctional motility of spermatozoa is associated with infertility. When situs inversus is present with the syndrome, it is known as Kartagener’s syndrome.

SITUS INVERSUS OF BRONCHI,- HYPARTERIAL BRONCHUS ON RIGHT, EPARTERIAL BRONCHUS ON LEFT

TWO LEFT SIDED FISSURES AND DEXTROCARDIA

This 30 year old male presents with a long standing history of a productive cough, headaches, and infertility. This obsolete study called a bronchogram outlines the bronchi with contrast revealing situs inversus of the bronchi. In the right upper lobe there are saccular accumulations of contrast representing a region of bronchiectasis. The stomach bubble can be seen on the right and hence there is situs inversus totalis. The heart is seen with apex pointed to the right and hence there is dextrocardia. So we can explain the cough from the bronchiectasis, but how do we explain the headaches and the infertility?

Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD 06248

Sinus views show a totally opacified maxillary sinus on the right, and an air fluid level on the left, consistent with acute sinusitis. The headaches are now explained. What about the infertility? Read on below

Courtesy Ashley Davidoff MD 06247