Air crescent sign

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging21(1):76-90, March 2006

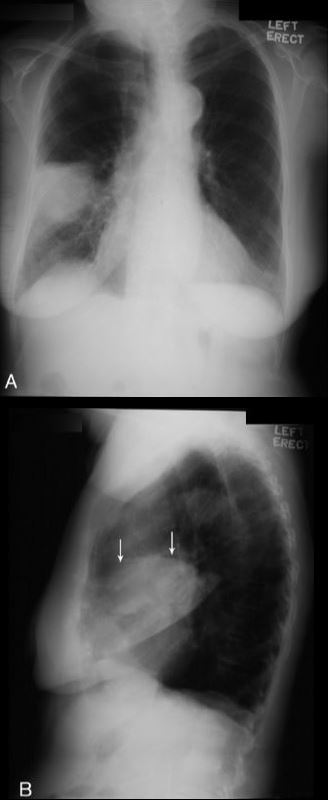

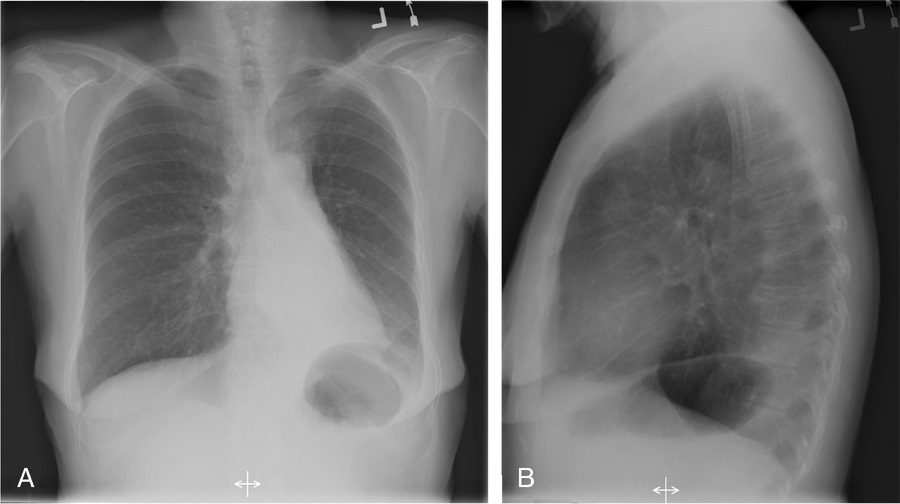

The air crescent sign appears as a variably sized, peripheral crescentic collection of air surrounding a necrotic central focus of infection on thoracic radiographs (Fig. 1A) and CT (Fig. 1B).2–4 It is often seen in neutropenic patients who have undergone bone marrow or organ transplantation and is most characteristic of infection with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. The fungus invades the pulmonary vasculature, causing hemorrhage, thrombosis, and infarction. With time, the peripheral necrotic tissue is reabsorbed by leukocytes and air fills the space left peripherally between the devitalized central necrotic tissue and normal lung parenchyma.5 Thus, the presence of the air-crescent sign heralds recovery of granulocytic function.4 Other causes of the air crescent include cavitating neoplasms, bacterial lung abscesses, and infections such as tuberculosis or nocardiosis.6

Bulging fissure sign

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging21(1):76-90, March 2006.

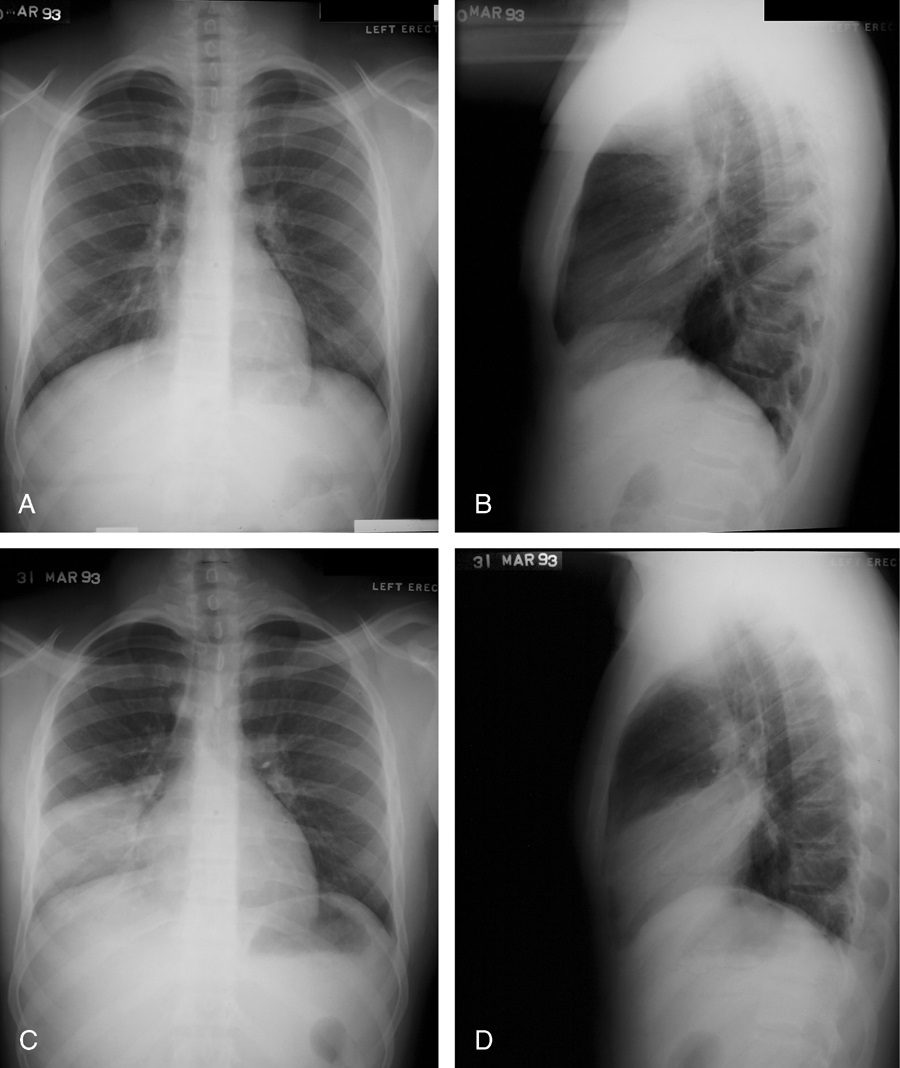

Classically, this sign is associated with consolidation of the right upper lobe (Fig. 2) due to Klebsiella pneumoniae infection.7 Due to the tendency for Klebsiella to produce large volumes of inflammatory exudate, the involved lobe expands and exerts mass effect on the adjacent interlobar fissure.8 The normally straight minor fissure on the lateral view bulges convex posteroinferiorly due to rapid lobar expansion.3,7 Although previously reported in up to 30% of patients with Klebsiella pneumonia,8,9 the finding is identified less commonly today, most likely due to rapid prophylactic implementation of antibiotics.3 Other less common causes of the bulging fissure sign include Hemophilus influenzae, tuberculosis, pneumococcal pneumonia, large lung abscesses, and lung neoplasms.10

CT halo sign

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

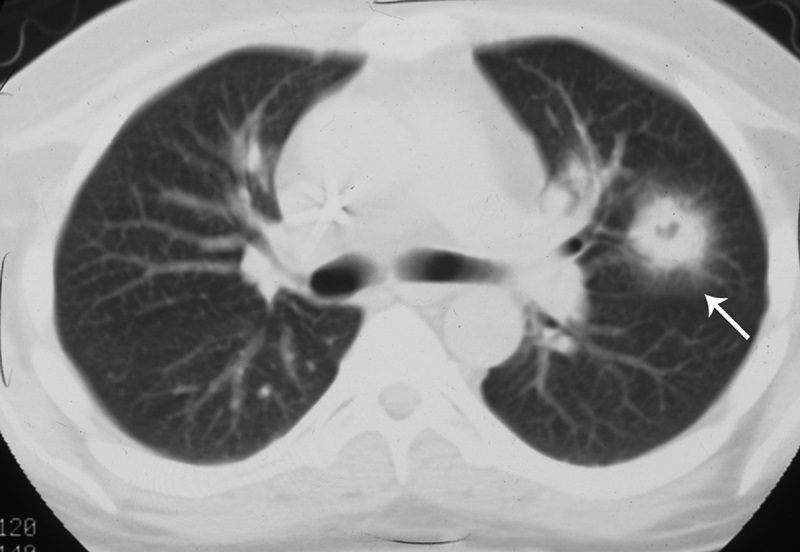

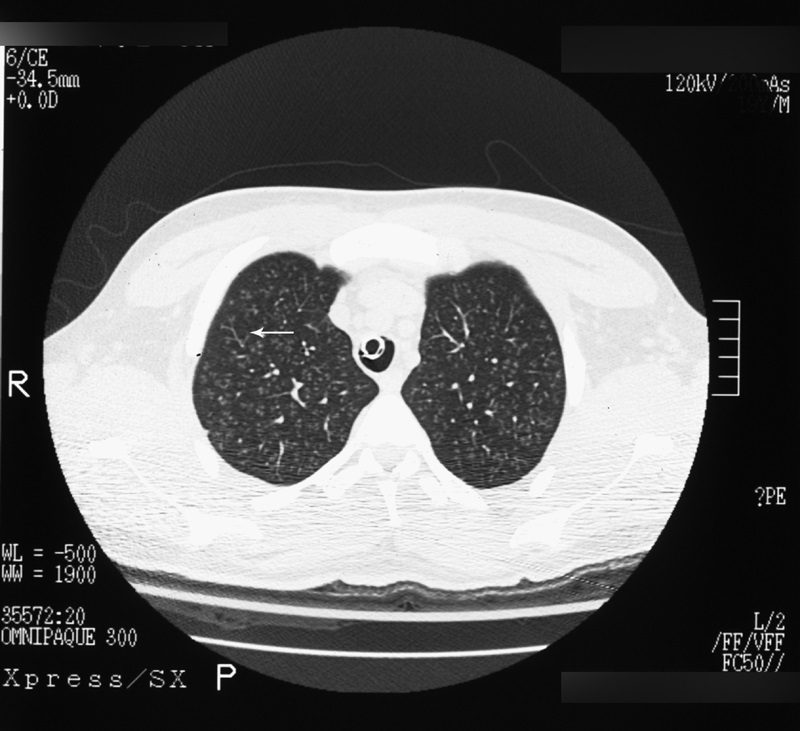

The CT halo sign appears as a zone of ground-glass attenuation around a nodule or mass (Fig. 7) on computed tomographic (CT) images.2–4,6,28 In febrile neutropenic patients, the sign suggests angioinvasive fungal infection, which is associated with a high mortality rate in the immunocompromised host.2–4 The zone of attenuation represents alveolar hemorrhage,2,4,6,28 whereas the nodules represent areas of infarction and necrosis caused by thrombosis of small to medium sized vessels.2–4,6,28,29 Other infectious causes include candidiasis, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and coccidioidomycosis.30 The CT halo sign may also be caused by non-infectious causes, such as Wegener granulomatosis, metastatic angiosarcoma, Kaposi sarcoma, and brochioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC).29,30 Due to the lepidic growth pattern of BAC, where the tumor cells spread along the alveolar walls, the typical ground glass halo visualized with the sign results.29

Finger-in-glove sign

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

Tubular shadows of soft tissue opacity akin to gloved fingers are seen on thoracic radiographs (Figs. 11A, B) and CT (Fig. 11C) and typically originate in the upper lobes in a bronchial distribution.2–4,36,37 The tubular, fingerlike projections represent dilated, mucoid-impacted bronchi surrounded by aerated lung. When an inciting stenosis or bronchial obstruction occurs, mucous glands will continue to produce fluid, while the secretions are continually taken to the site of narrowing by mucociliary transport.38 As the secretions become inspissated, debris accumulates distal to the point of obstruction, and bronchiectasis ensues. Visualization of the gloved fingers is made possible by collateral air drift through the interalveolar pores of Kohn and canals of Lambert aerating lung distal to the point of mucoid impaction. There are 2 broad etiologic categories: non-obstructive and obstructive.38 Non-obstructive causes, such as allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), asthma, or cystic fibrosis, are common considerations. ABPA is seen most commonly in asthmatic patients and occurs after inhaled Aspergillus organisms are trapped in airway mucus, triggering subsequent type I and type III allergic reactions.38 The acute type I response results in bronchoconstriction, heightened vascular permeability, wall edema, and protracted mucus production, whereas the delayed type III response causes immunopathological damage to the involved bronchi.38 Mucoid impaction in the setting of cystic fibrosis is secondary to mucociliary dysfunction and thick mucous secretions. Benign (bronchial hamartomas or lipomas) and malignant (bronchogenic carcinoma or carcinoid tumors) neoplasms are considerations in the obstructive category. Congenital obstructive causes, such as bronchial atresia, intralobar sequestration, or bronchogenic cysts, might also be considered.

Silhouette sign

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

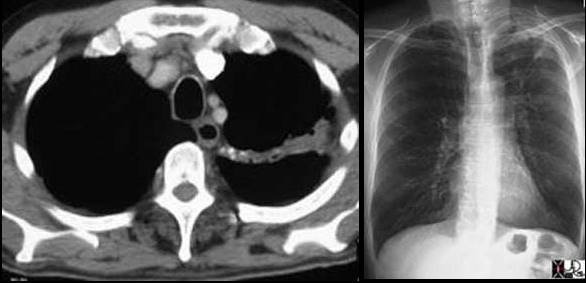

This classic roentgenographic sign first described by Felson in 1950 states that “an intrathoracic lesion touching a border of the heart, aorta, or diaphragm will obliterate that border on the roentgenogram. An intrathoracic lesion not anatomically contiguous with a border of one of these structures will not obliterate that border.”13,59,60 The underlying premise of the silhouette sign is that visualization of a roentgen shadow depends on a difference in radiographic density between adjacent tissues.13 For example, obscuration of the right heart border is often used to differentiate a right middle lobe process from a lower lobe abnormality (Fig. 20).3,4,60 Similarly, if the left heart border is partially or completely obliterated, the lingula is the region of involvement. Conversely, the absence of the silhouette sign can help in further localizing a lesion. With lower lobe disease, the right or left heart border on the side of involvement is preserved, whereas the silhouette of the hemidiaphragm is obliterated in cases of lower lobe collapse or consolidation (Fig. 21). The basic tenets of the silhouette sign are used to explain various other signs discussed previously, such as the cervicothoracic and hilum overlay sign.

Silhouette sign

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

If the left heart border is partially or completely obliterated, the lingula is the region of involvement. Conversely, the absence of the silhouette sign can help in further localizing a lesion. With lower lobe disease, the right or left heart border on the side of involvement is preserved, whereas the silhouette of the hemidiaphragm is obliterated in cases of lower lobe collapse or consolidation (Fig. 21). The basic tenets of the silhouette sign are used to explain various other signs discussed previously, such as the cervicothoracic and hilum overlay sign.

Split pleura sign

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

Separation and enhancement of the visceral and parietal pleural layers on CT (Fig. 22) is considered strong evidence of empyema.3,61 Normally, individual pleural layers are not discernable as discrete structures.3 Empyemic fluid fills the pleural space, resulting in thickening and enhancement of the pleura with a denotable separation.3,61

Tree-in-bud sign

Source

Signs in Thoracic Imaging

Journal of Thoracic Imaging 21(1):76-90, March 2006.

Best seen on high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) (Fig. 23), this sign appears as small, peripheral, centrilobular soft tissue nodules connected to multiple contiguous, linear branching opacities.3,4,62,63 This radiologic term represents the mucous plugging, bronchial dilatation, and wall thickening of bronchiolitis.3,4,62,63 The histopathological correlate demonstrates small airway plugging with mucus, pus, or fluid, with dilated bronchioles, peribronchiolar inflammation, and wall thickening. Anatomically, this sign relates to viscous fluid blocking the intralobular bronchiole of the secondary pulmonary lobule.63 Ordinarily the intralobular bronchiole is not visualized at HRCT (<1 cm); however, when filled with fluid and inflamed, the bronchiole becomes visible at the resolution of thin-slice CT.63 Although commonly associated with infectious etiologies such as endobronchial spread of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, recent evidence suggests that the sign is not specific for any one pulmonary disease, but includes other infectious entities such as Pneumocystis jiroveci (Pneumocystis carinii) pneumonia and invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. In addition, various immunodeficiency states, congenital disorders (cystic fibrosis), malignancy (lymphoma), panbronchiolitis,62 and aspiration are other etiologies in which tree-in-bud may be seen and, thus, clinical correlation is important in elucidating a diagnosis.3,4,62,63

Left image: In this patient with TB there is a linear band like density with calcifications in the LUL characteristic of atelectatic change in the LUL. This loss of volume is associated with fibrosis and retraction seen on the CXR in the following image. Courtesy of: Ashley Davidoff, M.D.

Left image: In this patient with TB there is a linear band like density with calcifications in the LUL characteristic of atelectatic change in the LUL. This loss of volume is associated with fibrosis and retraction seen on the CXR in the following image. Courtesy of: Ashley Davidoff, M.D.